Abstract

You probably like bees: they are cute and furry, and they pollinate our crops and wildflowers. In a world without bees we would go hungry, and our countryside would be very dull. But what about wasps? Wasps sting. They ruin your summer picnics. They nest in your house and make your parents angry. There is no reason to like wasps. At least, this is what most people think. Perhaps this is what you were taught in school, or by your family: see a wasp: swat a wasp! Scientists are challenging what people think about wasps and this article explains why we need to think differently about these insects. We will explain why most people do not like wasps and why we should care about them. We will also explain how scientists are asking for the public’s help to learn more about why wasps are important, and ultimately how to stop people from swatting the wasps.

Insects Rule the World, Unnoticed and Unloved

If you caught all the insects and vertebrates (animals with backbones) around the world and weighed them, which group would weigh more? Insects! Termites alone weigh more than all the birds in the world. If you then counted ALL the insects in the world, you would have something like 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 insects (or 1018–a trillion). If you sorted these insects by species, you would count up more species than in any other group in the animal or plant kingdoms. There are over 1 million species of insects already known, with another 4 or 5 million species possibly waiting to be discovered. In fact, 75% of all described organisms are insects [1].

Insects are found on every continent. They live in water, air, on land, and on or inside of other animals (even us!). Insects are extremely important: they help make food, they get rid of waste, they are pest-controllers, and they are gardeners in every ecosystem. Insects are 170 million years older than the dinosaurs, and they rarely go extinct. These are some of the reasons that studying insects is so fascinating and important. But, with so many insect species to choose from, scientists must make choices about which types of insects to study. The ones they usually choose to study are useful (like the bees that pollinate our crops and provide us with honey) or harmful (like mosquitoes, which carry diseases that can kill us), or just look awesome (like the 350,000 species of beetles that come in rainbow colors, with spots, swirls, and iridescence). But most insects go unnoticed (at best) or hated (at worst) by humans. One of these unloved insects is the wasp.

What is a Wasp?

There are over 150,000 species of wasps. Some are tiny and do not sting: these are parasitic wasps (Figure 1A), which lay their eggs inside the bodies of other arthropods (called “hosts,” like a caterpillar or spider). The parasitic wasp babies hatch and eat the host from the inside out! At least half of known wasp species are parasitic, and these wasps are very useful in crop agriculture as pest controllers—there are even factories that mass-produce these wasps to sell to farmers! You have probably not noticed these small, non-stinging wasps, despite their numbers and importance.

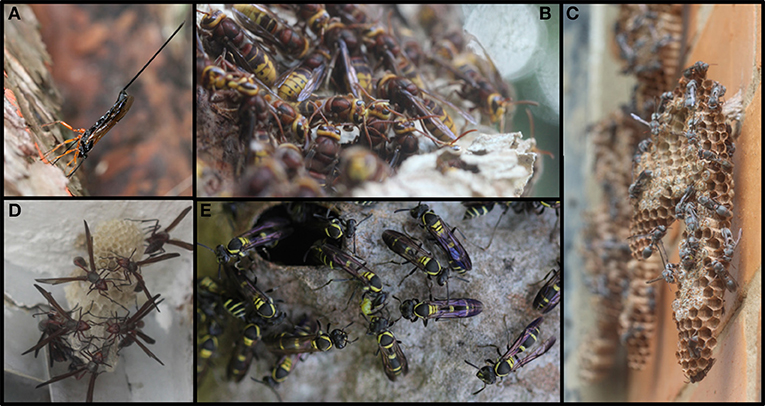

- Figure 1 - Diversity of wasps. (A) Parasitic wasp.

- These insects lay their eggs in the bodies of other insects. (B) European hornet from the UK. These are highly social species, with a single queen and about 100 daughter workers. (C) Social independent-founding wasp from Zambia, Africa. These wasps live in small groups of around 30–50 wasps. A single female will leave her home nest to start a new nest alone. (D) Another social independent-founding wasp from Zambia, Africa. These wasps are only found in Africa. They live in very small colonies of up to 10 wasps. Very little is known about them. (E) Social wasps from Trinidad and Tobago, Central America. These wasps live in large colonies with around 1,000 individuals. Images: (A) WikiMedia Creative Commons Richard Bartz Munich aka Mackro Freak_CC BY-SA 3.0; (C–E) the author; (B) Patrick Kennedy.

If you live in Europe or North America, you probably know wasps as the yellow and black striped yellow-jacket or hornet that has a nasty sting if you anger it at your summer picnic (Figure 1B). If you live in more tropical areas of the world (Southeast Asia, South America, or Africa), you might know wasps as small, blackish stinging flies that live in big paper nests (Figures 1C–E). These stinging wasps are the species you probably notice and might not like. You notice them because there are lots of them, in colonies just like honeybees. These are social wasps and, just like honeybees, they have a queen who lays the eggs and lots of workers who raise the brood. There are about 1,000 species of social wasps, but you have probably only noticed the species that are found nesting near (or in!) your house [2].

Why We Do Not Like Wasps

The wasps you notice do sting, but so do almost all the 22,000 species of bees and most of the 11,000 species of ants. The stinger of a wasp evolved from an ovipositor—the tube used by female insects to lay eggs. Bees, wasps and ants evolved stings to defend themselves and their nests, or to hunt prey. Wild bees are just as likely to sting you as wild wasps are. “I do not like wasps because they sting,” is not a good excuse to swat the wasp. And anyway, it is only the female wasps that sting: males do not have a stinger.

Reasons to Like Wasps

Like many insects, wasps carry out lots of important jobs in nature, which help us to live healthy and happy lives. These jobs are called ecosystem services [3]. The most important ecosystem service provided by wasps is pest control. Wasps are predators, which means they hunt live prey (like flies, caterpillars, and spiders) as a source of protein. The wasps that you see out and about are the hunting adults. But, the adults do not eat the prey; they feed it to the developing brood. It is the baby wasps that are the meat-eaters, not the adults. In social wasp species, the babies give the adults that feed them a sugary reward. So, predator wasps help to keep other arthropod populations under control. Without these wasps, we would be flooded with flies, caterpillars, spiders, and other arthropods. Wasps provide us with free, eco-friendly natural pest-control services. In a world without wasps, we would need to use more toxic pesticides to control the insects that eat our crops and carry diseases.

Wasps also pollinate. Remember, the adult wasps do not eat the prey; instead, they gather and eat sugar from the nectar of flowers, or from your sugary drinks! They pollinate the flowers they visit, just like bees do. But wasps are not as fussy as bees—they will visit any flower. This means wasps might not be as efficient at pollination as bees are. However, being less fussy means that wasps may be useful back-up pollinators in habitats, such as cities and farmland, where there are not enough of the right kinds of flowers for bees to thrive. Wasps may become more important pollinators in the future, as more of the natural world becomes disturbed and urbanized by humans.

Why We Do Not Like Wasps

Despite the ecosystem services provided by wasps, wasps are unloved by both scientists and the public. A recent study that I performed with my student, Georgia Law, and my colleague, Dr. Alessandro Cini, suggested that the reason we hate wasps is that most people do not understand how important wasps are in ecosystems [4].

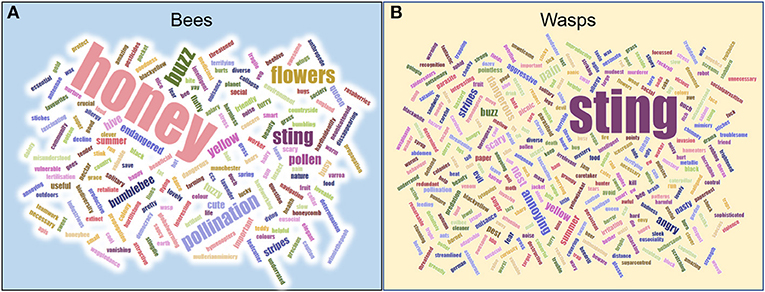

Using social media and an online survey, we asked 750 members of the public how they feel about bees and wasps [4]. People described bees in very positive terms, using words like “pollinator,” “honey,” and “useful” (Figure 2A). In contrast, people overwhelmingly used the word “sting” to describe wasps (Figure 2B). So, even though both bees and wasps sting, “sting” was used to describe wasps, but not bees. Also, even though wasps are useful, people used the words “useful” for bees, but not wasps. This shows that people have some important misconceptions about wasps.

- Figure 2 - Words used by 750 members of the public to describe bees (A) and wasps (B).

- The size of the word reflects the number of people who used that word in their descriptions. You can see that people used different words to describe wasps and bees, some of which show their lack of knowledge about the importance of wasps. Created with online software at www.wordle.com.

We also asked people to tell us how important bees and wasps are in providing ecosystem services. Almost everyone appreciated the importance of bees as pollinators but, by contrast, people did not appreciate the importance of wasps as pest controllers. This study told us that people dislike wasps because they do not appreciate the ecosystem services wasps provide. Perhaps, now that you know more about the value of wasps, you will be less likely to swat them.

The Public Helps Us Learn More About Wasps

Scientists are partly to blame for people’s ignorance about wasps. Because there have not been many studies of wasps, there are a lot of unanswered questions about them, like, Where do wasps like to live? How far does a wasp fly to find food? What is the economic value of wasps as pest controllers? We know the answers to these important questions for bees, but we need to start answering them for wasps.

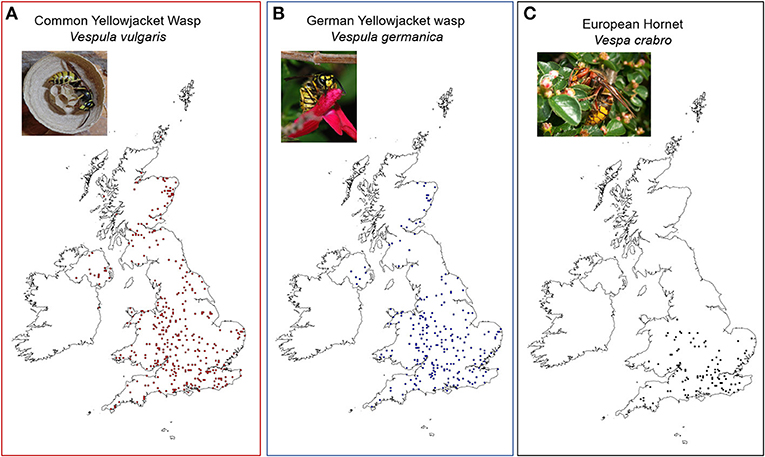

We asked the public to help us answer some of these questions. This type of approach is called citizen science. In citizen science, scientists ask the public to help gather data or analyze it. In 2017, Professor Adam Hart and I launched the Big Wasp Survey in the UK. We asked people to make wasp traps, hang them in their gardens for 7 days, and send us the wasps they caught. We identified the wasps and made a map of where the different species of wasps are in the UK (Figure 3). In just 2 weeks, this project generated data on wasps from over 1,200 locations across the UK [5]. We are now using these data to understand how species differ in their abundance in different habitats, how far wasps disperse, how urbanization is affecting wasp populations, and whether new, invasive species, like the yellow-legged Asian hornet, are present. By taking part in this citizen science project, we also hope that the public will become more appreciative of these unloved insects and less inclined to swat them.

- Figure 3 - Distribution maps of common social wasps in the UK, obtained from 6,680 wasps collected by members of the public in the Big Wasp Survey 2017.

- Each point represents a trap. (A) 44% of all wasps caught were Vespula vulgaris (2,942 wasps from 407 traps). (B) Another 44% of wasps caught were Vespula germanica (2,974 wasps from 251 traps). (C) 6% of wasps caught were the European hornet, Vespa crabro (395 wasps from 100 traps). The other 2% were from other rarer species. These data shows us how widespread Vepsula are across the UK, whilst hornets are largely limited to more southern regions. Details of each trap contents can be found in the interactive map for 2017 data, on www.bigwaspsurvey.org. Image credits: Wikimedia Creative Commons. (A) FrankHornig CC BY-SA 3.0; (B) Vespulagermanica_ Alvesgaspar_ CC BY-SA 3.0; (C) MFbay_Vespulagermanica _Alvesgaspar_CC BY-SA 3.0.

Are You a Wasp Convert?

Wasps are one of the most misunderstood organisms on the planet. Yet, they are nature’s pest controllers. We have learned to love bees and appreciate their role in the environment, despite their sting. We need to learn to love wasps and better understand their contributions to the environment, too. Citizen science is a powerful way to help scientists learn about wasp biology and will hopefully persuade the public to not swat the wasp.

Glossary

Arthropod: ↑ An animal with an external skeleton, segmented body, and jointed legs. Insects, such as wasps, and spiders are arthropods.

Ecosystem Services: ↑ Benefits provided by organisms, such as insects that help us live healthy and enjoyable lives. Pest control by wasps is an ecosystem service.

Natural Pest-control: ↑ Non-toxic ways of killing pests, using the natural behaviors of wild organisms.

Citizen Science: ↑ Scientific research in which members of the public help gather data or analyze it in some way.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Sumner, S., Law, G., and Cini, A. 2018. Why we love bees and hate wasps. Ecol. Entomol. 43:836–45. doi: 10.1111/een.12676

References

[1] ↑ Bar-On, Y. M., Phillips, R., and Milo, R. 2018. The biomass distribution on earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115:6506–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711842115

[2] ↑ Bell, E., and Sumner, S. 2013. Ecology and Social Organisation of Wasps. Chichester: eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0023597

[3] ↑ Noriega, J. A., Hortal, J., Azcárate, F. M., Berg, M. P., Bonada, N., Briones, M. J. I., et al. 2017. Research trends in ecosystem services provided by insects. Basic Appl. Ecol. 26:8–23. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2017.09.006

[4] ↑ Sumner, S., Law, G., and Cini, A. 2018. Why we love bees and hate wasps. Ecol. Entomol. 43:836–45. doi: 10.1111/een.12676

[5] ↑ Sumner, S., Bevan, P., Hart, A. G., and Isaac, N. J. B. 2019. Mapping species distributions in two weeks using citizen science. Insect Conserv. Divers. 12:382–8. doi: 10.1111/icad.12345