Abstract

Have you ever seen an urban floodplain? These are areas around a river within the city that can fill with water when it rains a lot. Since there are many streets and buildings, the water cannot seep into the ground and ends up flooding these areas. Urban floodplains often go unnoticed; worse, they are seen as areas that should be filled in or developed. However, these aquatic ecosystems are very important for the local environment because they help control river floods, maintain water quality, and are the homes of many plants and animals. In this article, we will explore the importance of urban floodplains and the challenges people face in protecting them. In addition, we propose an educational activity—a field trip through a local urban floodplain—to educate the community and involve them in floodplain conservation.

Urban Floodplains: Fragile and Poorly Protected Ecosystems

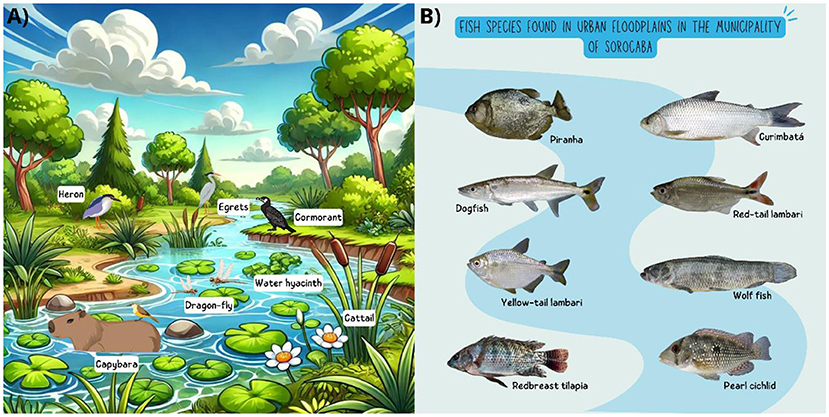

Urban floodplains are wetland areas in the city, created when water levels in a nearby river rise, overflow the river’s banks, and temporarily flood local, low-lying areas. This flooding primarily happens during the rainy season. Even if you are a city dweller, you may not have noticed urban floodplains before—but these watery areas are like secret ecosystems in the middle of the city (Figure 1). Understanding urban floodplains and their benefits can make us feel more connected to these incredible environments and motivate us to protect them!

- Figure 1 - Urban floodplains are low-lying areas in cities that are flooded when nearby rivers rise during the rainy season.

- They are great places for exploring and observing wildlife. Urban floodplains of the Sorocaba River will be visited during the field trip we propose in this article (Image generated using DALL-E by OpenAI).

Urban floodplains are vital areas for a wide variety of species, including fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals, and aquatic invertebrates (Figure 2A). These areas provide habitats essential for the reproduction, shelter, and feeding of all these animals. Floodplains are particularly essential for fish, as the young forms of many migratory fish species, such as the Curimbatá in South America, develop there. Several species of fish live in urban floodplains during rainy periods when the river level is high, while others live in the floodplains during their entire life (Figure 2B). During the dry season when there is no flooding, fish can live off of fat reserves accumulated during the rainy season, and they can shelter in the pools of water that do not dry up, or move to more suitable areas [1, 2].

- Figure 2 - (A) Biodiversity found in urban floodplains of Sorocaba, Brazil (Image generated using DALL-E by OpenAI).

- (B) Fish species found in urban floodplains of Sorocaba, Brazil.

One of the fundamental components for maintaining urban floodplains is the presence of water plants known as macrophytes. They play essential roles in floodplains by providing habitat, adding oxygen to the water, and filtering the water [3]. Additionally, macrophytes serve as food for fish, terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates, algae, and microscopic organisms called phytoplankton and zooplankton.

Urban floodplains act as natural filters, cleaning the water and removing harmful substances like excess sediment, chemicals and nutrients in high concentrations (such as nitrogen and phosphorus), which can cause water to go bad for animals and plants to live healthy [4]. Despite the high biodiversity of urban floodplains and the environmental services they provide, many people only see them as problematic areas prone to flooding. Many people would rather see them filled in and developed. Understanding and protecting floodplains is crucial to the health of our urban environments. If we can get people involved in this cause, we can help ensure that these incredible places remain an important part of a city.

Ecosystem Services Offered By Urban Floodplains

Urban floodplains provide humans with four basic types of ecosystem services [5, 6]. First, they provide clean water, food resources (organic matter, insects and other invertebrates, aquatic plants and algae, fish and amphibians, fruits, and seeds), and ecosystem services of economic value. Second, they can help to prevent populated areas from flooding and can reduce erosion (a natural process of soil wear), which contributes to soil protection, riverbank stability, and the preservation of urban and rural infrastructure. Third, they provide cultural benefits—these areas can be beautiful, and they can be spaces for leisure activities, tourism, and environmental education. Finally, urban floodplains are the homes of many, many plants and animals [7, 8].

The Sorocaba River as a Model for Environmental Education

The Sorocaba River is an important river in the State of São Paulo, Brazil. It is a main tributary of the Tietê River [9]. One can find hundreds of floodplains in both rural and urban areas along the Sorocaba River. These ecosystems are permanent or exist only during certain times of the year [10]. The urban floodplains of the Sorocaba River are close to residential neighborhoods and places where the local community can easily access them.

As part of its efforts to teach people about the importance of preserving the Sorocaba River, Brazil’s Department of the Environment established the Sorocaba River Field Trip [11]. The field trip was designed to reach three distinct groups separately. One field trip was aimed at teenagers and adults, another targeted younger children, and the third field trip was intended for the elderly or people with disabilities.

Field Trip to the Floodplains: A Strategy for Their Conservation

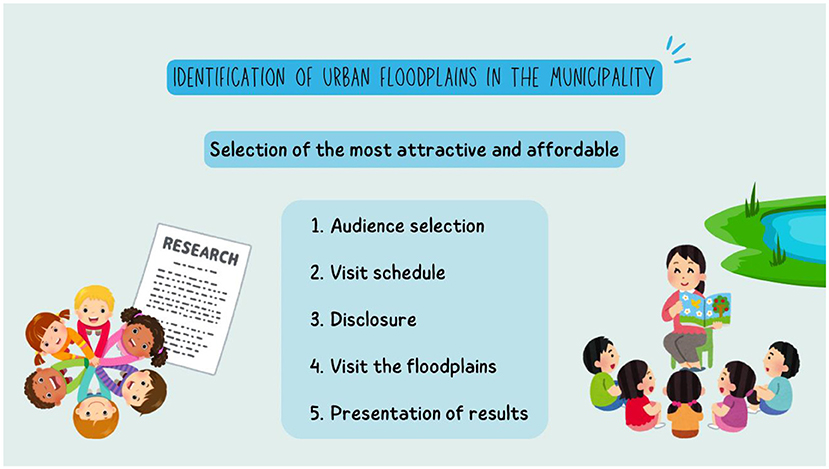

Considering the previous environmental education actions related to the Sorocaba River, we propose that a similar field trip could be created for urban floodplains (Figure 3).

- Figure 3 - Plan for organizing a field trip through urban floodplains.

To get people interested and select an audience, we first need to create a schedule and publicize it to reach as many people as possible. City agencies and local universities can help us develop the plan and spread the word. After all the field trips are completed, we are curious to analyse all the results and publish them so that more people learn from our experience, and for city officials to monitor the evolution of the project through the perspective of educators and visitors.

Details of the Sorocaba Field Trip

In Sorcaba, we developed a field trip route along several nearby urban floodplains. So, we selected five floodplain areas that would be most suitable for teaching people about urban floodplains. Each of these floodplains are different, so people can learn something different in each one. At first, we will have one set script for the guide, which can be modified slightly according to the participating audience. Later, the script can be adapted for specific audiences, such as schools, audiences with greater knowledge of the topic, or teenage audiences, among others.

In each floodplain a different and specific aspect will be addressed. In flood plains where fishing is common, the field trip guide can mention the fish and other species present there. In a floodplain that is or was polluted with sewage, the guide can highlight the importance of keeping the water clean, both for public water use and for the ecosystem. Furthermore, guides can mention the environmental benefits that happen when floodplains are healthy and cared for. Guides, can also explain how the level of connection between a floodplain and the river increases biodiversity.

Final Consideration

The creation of guided tours to urban floodplains allows children and other people to learn about the importance of aquatic ecosystems and how they contribute to the conservation of these ecosystems. In Sorocaba, children have become the guardians of urban wetlands because they learned about the importance of protecting nature, and shared it with their families and friends. So, are you ready to become a nature’s guardian and protect the plants and animals in the place where you live? They are counting on you!

Glossary

Floodplains: ↑ Areas near rivers that get covered with water during floods.

Invertebrates: ↑ Animals that do not have a backbone, such as insects, mollusks, crustaceans, and worms.

Macrophytes: ↑ Aquatic plants that can be seen without a magnifying glass, important for ecosystems because they provide shelter for other living things and help keep the water clean.

Biodiversity: ↑ The variety of living things on Earth, like different types of plants, animals, and microorganisms.

Ecosystem Services: ↑ Important benefits that nature gives us, like clean air, clean water, and food.

Environmental Education: ↑ Learning about the environment to motivate people to take care of and protect nature.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Postgraduate Program in Environmental Engineering Sciences at São Carlos School of Engineering - USP for the development of this work and Laboratório de Ecologia Structural e Functional de Ecossistemas - UNIP campus Sorocaba for the logistical support. To Prof. Dr. Francisco Langeani for the identification of the species and deposit in the Fish Collection of the Department of Zoology and Botany of the State University of São Paulo “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” São José do Rio Preto, SP (DZSJRP), to André Luis Minghêti Puga for his assistance in all fieldwork, the CAPES Process 1681410 scholarship granted to the first author, the CNPq Process 130957/2023-2 scholarship granted to the third author and the Vice-Rector of Postgraduate Studies and Research for the scholarship to the fourth author.

AI Tools Statement

The authors would like to acknowledge the use of DALL-E by OpenAI for generating the images in this study, facilitated by the assistance of ChatGPT.

References

[1] ↑ Correa, S. B., Sleen, P., van der., Siddiqui, S. F., Bogotá-Gregory, J. D., Arantes, C. C., et al. 2022. Biotic indicators for ecological state change in amazonian floodplains. Bioscience 72:753–768. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biac038

[2] ↑ Mosepele, K., Kolding, J., Bokhutlo, T., Mosepele, B. Q., and Molefe, M. 2022. The Okavango Delta: fisheries in a fluctuating floodplain system. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:854835. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.854835

[3] ↑ Oliveira, L. S., Cajado, R. A., dos Santos, L. R. B., Suzuki, M. A. L., and Zacardi, D. M. 2020. Bancos de macrófitas aquáticas como locais de desenvolvimento das fases iniciais de peixes em várzea do Baixo Amazonas. Oecol. Austr. 24:644–660. doi: 10.4257/oeco.2020.2403.09

[4] ↑ Corrêa, C. S., and Smith, W. S. 2019. Hábitos alimentares em peixes de água doce: uma revisão sobre metodologias e estudos em várzeas brasileiras. Oecol. Austr. 23:698–711. doi: 10.4257/oeco.2019.2304.01

[5] ↑ da Silva, F. L., Stefani, M. S., Smith, W. S., Schiavone, D. C., da Cunha-Santino, M. B., and Junior, I. B. 2020. An applied ecological approach for the assessment of anthropogenic disturbances in urban wetlands and the contributor river. Ecol. Compl. 43:100852. doi: 10.1016/j.ecocom.2020.100852

[6] ↑ da Silva, F. B., Stefani, M. S., Smith, W. S., da Cunha-Santino, M. B., and Junior, I. B. 2019. The municipality role in Brazilian wetlands conservation: the establishment of connections among the Master Plan, the National Hydric Resources Policy and two international strategic plans. Rev. Brasil. Geogr. Física. 12:2193–2203. doi: 10.26848/rbgf.v12.6.p2193-2203

[7] ↑ Assessment Millennium Ecosystem. 2005. Ecosystems and human well-being: wetlands and water. Washington, DC: World resources institute.

[8] ↑ da Silva, F. L., Smith, W. S., da Cunha-Santino, M. B., and Junior, I. B. 2021. Áreas úmidas brasileiras: bases para o gerenciamento, serviços ecossistêmicos e estratégias de manejo. Rev. Caminhos Geogr. 22:97–111. doi: 10.14393/RCG227953473

[9] ↑ Smith, W. S. 2003. Os peixes do rio Sorocaba: a história de uma bacia hidrográfica. Sorocaba, SP: Editora TCM, 160.

[10] ↑ Smith, W. S., and Barrella, W. 2000. The ichthyofauna of the marginal lagoons of the Sorocaba River, SP, Brazil: composition, abundance and effect of the anthropogenic actions. Rev. Bras. Biol. 60:627–632. doi: 10.1590/S0034-71082000000400012

[11] ↑ Castellari, R. R., Teixeira, A. J. B. L., and Smith, W. S. 2014. “Tour do Rio Sorocaba - uma proposta para educação ambiental em ambiente urbano”, in Conectando peixes, rios e pessoas: como o homem se relaciona com os rios e com a migração de peixes, ed. W. S. Smith (Prefeitura Municipal de Sorocaba: Secretaria do Meio Ambiente), 50–59.