Abstract

Distributing resources between individuals often leads to difficult dilemmas. Imagine, for example, a father who wants to give out five lollipops to his two daughters. He can give two lollipops to one girl and three to the other, which will make things unequal between the two girls. Alternatively, he can give two lollipops to each girl and throw away the fifth. This will maintain equality but will be wasteful. In this article, we will review recent findings on how children and adults resolve the tension between unequal distribution and waste. In particular, we will describe findings showing that children, and even adults, often waste resources to avoid inequality. This tendency develops at a young age and is observed in multiple countries. Finally, we will describe ways to distribute resources fairly without wasting them, which can make people feel good and avoid waste.

One Basketball Game Ticket, Two children…

Not long ago, one of the authors of this article, Shoham, was offered two prime-location tickets to a popular basketball game. Shoham hesitated. Raanan and Shalev, her two sons, both dreamt of going to such a game. But having only two tickets—one of which must be used by the accompanying adult—means that only one child could attend the game. That is, Shoham would not be able to take both boys and would have to choose who could go. Shoham thought that it might be easiest to give up the tickets and not take either of her children. That way, there would be equality between the children and no one would be offended. Yet she also felt it was a shame to forfeit a wonderful experience for the child who could go to the game.

Resource allocation dilemmas like this one are common. They occur whenever people want to distribute resources but cannot do so in an equal manner. In such cases, there is a conflict between two important ideas: “be fair” [1], and “do not waste”. In the rest of this article, we will describe these principles, then we will explain how children and adults resolve such conflicts. Finally, we will offer solutions for preventing waste while maintaining fairness, and, of course, we will reveal what Shoham decided to do with the tickets.

Research on human behavior teaches us that both children and adults show inequality aversion, which means that they hate to find out that resources are being distributed in an unequal way [2]. It will surely not surprise you that nobody likes to get the smallest piece of cake. People not only hate to receive less than others, but they also dislike distributing resources unequally among other people [3].

Revisiting the lollipops example, consider how you would feel if asked to divide five lollipops between two friends. Giving three lollipops to one friend and only two to the other might make you uncomfortable, and it might make one of the friends feel like they are experiencing discrimination. You may also fear that other children will judge you for making what looks like a biased decision.

You will also probably not be surprised to learn that people do not like to waste resources, either. From a young age, we are taught that it is important to behave with efficiency and to use all the resources available to us. For example, we do not like to throw food in the trash (certainly not cake!), and we try to recycle. Therefore, the idea of throwing candy in the trash, or giving up valuable tickets, bothers us.

Inequality Vs. Waste—Which Wins?

How do people solve dilemmas that pit inequality and waste against each other? To answer this question, Prof. Shoham Choshen-Hillel with Prof. Alex Shaw from the University of Chicago and other colleagues conducted a series of experiments and found that people often choose to waste resources to avoid inequality [4]. For example, in an experiment conducted in the USA, Israel, and China, children aged 6–8 were asked to distribute five colored erasers to two children, Michael and Dan. The children were told that Michael and Dan each received two erasers, and they were asked to decide what to do with the fifth eraser—give it to Michael or throw it in the trash (Figure 1).

![Figure 1 - The participants in our experiment (aged 6–8) [4] were told that two other children, Michael and Dan, were each given two erasers.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1286330/frym-11-1286330-HTML/image_m/figure-1.jpg)

- Figure 1 - The participants in our experiment (aged 6–8) [4] were told that two other children, Michael and Dan, were each given two erasers.

- The participants were asked to decide what to do with a fifth eraser: give it to Michael or throw it in the trash. If they give the fifth eraser to Michael, it will create inequality between Michael and Dan. If they throw the eraser in the trash, there will be equality but the eraser will be wasted. Most children chose to throw the fifth eraser in the trash (Photo credit: Prof. Shoham Choshen-Hillel).

The findings of the study were clear: In the USA and in Israel, more than 90% of children chose to throw the fifth eraser in the trash, thus preferring waste to inequality. In China, most children also chose to discard the fifth eraser, but less so than in the USA and Israel (about 70%, see Figure 2). Why did the children in China discard the fifth eraser less often than the other children? We hypothesized that, compared to the children in the USA and in Israel, the Chinese children found the erasers to be more valuable, and therefore they were less willing to throw them away. When we asked children in the three countries to divide resources with different costs—markers, smartphones, or money—the more expensive the resource, the less likely the children were to throw away the item. Even so, about half of the children still chose to throw the smartphones and the money in the trash! That is, children tend to waste resources to avoid inequality, but they waste less if they feel the resources are more valuable.

![Figure 2 - We conducted our experiment [4] on 70 children, ages 6–8, in the USA, Israel, and China.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1286330/frym-11-1286330-HTML/image_m/figure-2.jpg)

- Figure 2 - We conducted our experiment [4] on 70 children, ages 6–8, in the USA, Israel, and China.

- The graph shows the percentage of children who chose to throw away the fifth eraser in each country. In the USA and Israel, more than 90% of children chose to throw away the fifth eraser. In China, only 70% chose to throw away the fifth eraser. This means that most children preferred to waste resources than to create inequality (Figure credit: Yair Nahari).

Are adults also willing to waste resources to ensure equality? As it turns out, yes! We asked adults to imagine that they were managing a company and had to decide what to do with a new, state-of-the-art computer—give it to one of two outstanding employees or leave it in the box and not give it to anyone. Most participants said they would leave the computer in the box. They thought that if they gave it to one employee, others would say that they were unfair.

Let us return to the story of Shoham and the basketball tickets. To avoid being seen as favoring one of her children, and to avoid offending the other, she decided to give up the tickets, so that no one would go to the game. That is, she too chose waste over inequality.

Balancing Inequality and Waste: A Win-Win Solution?

So far, we have seen that both children and adults tend to waste to maintain equality. But is there a way to preserve equality without wasting? One option is to hold a lottery. For example, you can divide five candies between two girls by tossing a coin and determining, ahead of time, that the winner will receive three candies, and the loser will receive two. Note that one girl will still receive more than the other—but because each girl had an equal chance of winning to begin with, the decision feels fair. Our studies show that when an unequal decision is made using a random lottery, it does not seem unfair. The principle of fairness is preserved, and waste is avoided.

But people do not always like to base their decisions on random processes like a lottery. A lottery could still leave those who lost feeling sad or bitter. For instance, imagine how one of Shoham’s sons would feel if he lost the ticket to the game after a coin toss.

Another method we proposed for solving dilemmas between inequality and waste is to hand over the decision to the person who may receive less. For example, instead of the mother deciding which child gets the ticket, she could ask one son if he prefers to give the ticket to his brother or if he prefers that neither of them get the ticket. We found that, in some cases, the child who would not receive the resource anyway would still choose to give it to the other child [5]. The giving child will even feel proud, generous, and powerful since the other child received the resource thanks to his generosity. Note that, if the mother had decided to give the ticket to one of the children, the other would probably have been angry and felt that he was being discriminated against. But if he is the one who chooses to give his brother the ticket, the exact same result will make him happy (Figure 3).

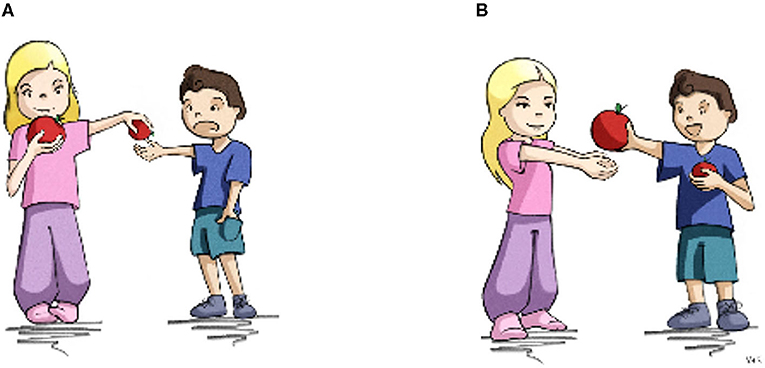

- Figure 3 - People can react differently to the same unequal distribution, depending on who makes the allocation.

- (A) The boy is sad when the girl takes the larger apple and gives him the smaller one. (B) The boy is happy with the same result if he is the one who decides the girl will get the bigger apple (Figure credit: Yoav De-Shalit).

Summary

Understanding that people are less bothered by receiving a smaller share of resources when they create the inequality themselves provides a great solution to our dilemma. Instead of a third person deciding how to allocate the resources (e.g., the mother), we can hand over the decision to the person who would potentially receive less (e.g., one of the sons). In this case, the child will sometimes choose to waste the resource and not give it to the other child—just as Shoham decided. But other times, the child will choose to give the resource to his brother, and both will be happy. If this happens, the distribution will not only be equal and feel fair, but no resources will be wasted. That is a win-win!

Glossary

Equality: ↑ Distributing resources such that each person gets the same as others. For example, giving one cookie to each student in class.

Resource Allocation Dilemmas: ↑ Situations that make it difficult to decide how to divide resources between people. For example, how to divide an odd number of lollipops between an even number of children.

Inequality Aversion: ↑ An unpleasant feeling that arises when we feel that resources have been distributed unequally. For example, when you find out that you received a smaller piece of pie than your peers.

Discrimination: ↑ Treating certain people worse than others, without any justifiable reasons. For example, a teacher who gives lower grades to students with green eyes.

Efficiency: ↑ Maximum use of resources while avoiding waste. For example, eating all of your dinner without throwing anything out.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Israeli Science Foundation (ISF) grant # 354/21 (to SC-H) and the Recanati fund at the Hebrew University Business School (to SC-H).

References

[1] ↑ Messick, D. M. 1993. “Equality as a decision heuristic,” in Psychological Perspectives on Justice: Theory and Applications, eds B. A. Mellers, and J. Baron (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). p. 11–31. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511552069.003

[2] ↑ Fehr, E., Bernhard, H., and Rockenbach, B. 2008. Egalitarianism in young children. Nat. 454:1079–83. doi: 10.1038/nature07155

[3] ↑ Shaw, A. 2016. “Fairness: what it isn’t, what it is, and what it might be for,” in Evolutionary Perspectives on Child Development and Education (Cham: Springer). p. 193–214. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-29986-0_8

[4] ↑ Choshen-Hillel, S., Lin, Z., and Shaw, A. 2020. Children weigh equity and efficiency in making allocation decisions: evidence from the US, Israel, and China. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 179:702–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2019.04.006

[5] ↑ Choshen-Hillel, S., and Yaniv, I. 2011. Agency and the construction of social preference: between inequality aversion and prosocial behavior. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 101:1253–61. doi: 10.1037/a0024557