Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can occur when someone experiences a scary event or serious injury. This disorder can affect multiple parts of a person’s life, from relationships with loved ones to performance at work. Unfortunately, PTSD is not understood well. It is considered an invisible disability, which means it can be difficult to determine if someone has PTSD just by looking at them, since they have no visible symptoms. Because of the difficulty of diagnosing PTSD, healthcare professionals are working toward checklists that can be used by all doctors for PTSD diagnosis and treatment, which will hopefully improve the care of PTSD patients. Similarly, disability activists continue to raise awareness and educate the public on PTSD. In this article, we will discuss the causes of PTSD, its effects on daily life, diagnosis, treatment, and the importance of showing kindness toward people with this invisible disability.

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a big term, but we can understand it by breaking it down. Trauma is a deeply distressing experience, like a physical injury or an emotional experience. “Post-” is a prefix that means “after,” so “post-traumatic” means that a person has experienced something scary in the past. The final part of the term, “stress disorder,” refers to problems that will affect the person afterwards. Putting it altogether, PTSD is a mental health condition that develops from a distressing event. PTSD does not occur in any one group of people or result from one specific type of incident; it can arise from various experiences.

People with PTSD might experience bad memories or nightmares that remind them of the previous traumatic incident. They sometimes also avoid people or places associated with the event. For example, veterans with PTSD might choose to avoid war museums because such places may remind them of combat. People with PTSD might also be especially sensitive to certain sights or sounds. Veterans might find fireworks disturbing, as the sounds may remind them of loud guns. Similarly, a survivor of a major earthquake might find a news report on another natural disaster disturbing.

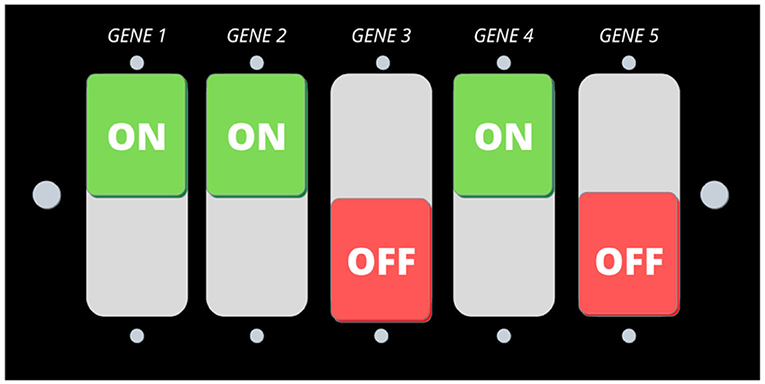

Very few people who experience traumatic events actually develop PTSD. For this reason, researchers are working hard to figure out why some people develop PTSD while others do not. Scientists, doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals think development of PTSD has to do with the way that our external environments (such as where we live and our support systems) can interact with our genes. Previously, it was thought that PTSD was caused only by genes. However, we now know that our genes can be affected by everything around us. Some people are more likely to develop PTSD after a traumatic event if they carry certain genes. Some people might also be at risk of developing PTSD if the traumatic event turns certain genes on or off. Genes can be turned on or off, similar to light switches (Figure 1). A traumatic event can flip these switches just enough for a person to develop PTSD. Clearly, there are a lot of different factors that could lead to the development of PTSD. However, we still need to better understand these factors and their interactions.

- Figure 1 - PTSD is believed to be caused by a combination of genes and environment.

- Genes can be switched “on” and “off,” similar to a light switch. A traumatic event can sometimes flip these switches just enough for a person to develop PTSD.

Effects of PTSD on Daily Life

PTSD can have many effects on a person’s daily life and relationships. Researchers have found that the more severe a person’s PTSD symptoms are, the more aggressive the person’s behavior tends to be [1]. People with severe PTSD may act out toward their friends and family or avoid talking about their feelings. At times, they may seem disconnected from everything around them, i.e., they might not respond if their friends and family try to talk to them. They may also avoid potentially triggering places or events, which can make going to friends’ houses or birthday parties difficult. If people with PTSD do not explain why they do not visit, their loved ones may be confused and hurt. The effects of PTSD on daily life and relationships are challenging, both for people with PTSD and their loved ones, but resources are available. Resources, such as the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), a support group, or talking to a therapist can be helpful.

How is PTSD Diagnosed?

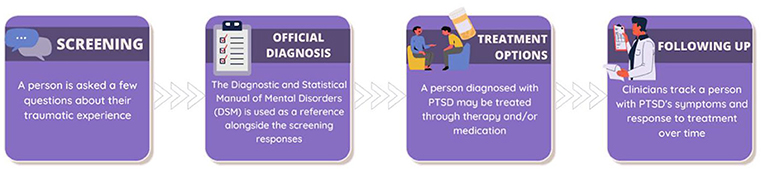

There are several steps to determine if someone has PTSD (Figure 2) [2]. The first step is screening, during which the person is asked a few questions about their experiences. One common question set used in screening is called the Brief Trauma Questionnaire. This questionnaire asks 10 questions about serious life events, such as major injuries or anything that put the person’s life in danger, to assess the level of trauma the person has experienced [3]. The second step involves using a universal checklist created by healthcare professionals and researchers to make an official diagnosis. This checklist is made up of criteria for diagnosing someone with PTSD, such as certain behavioral and bodily symptoms. The criteria can be found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), a book that lists and describes all known mental illnesses. For someone to be diagnosed with PTSD, that person must have had symptoms for at least 1 month. After diagnosis, doctors track the person’s symptoms and response to treatment over time. This step includes self-reports that patients complete each time they go to the doctor’s office. One commonly used self-report is a checklist from the DSM, which includes 20 questions about how often a patient has experienced different PTSD symptoms.

- Figure 2 - There are several steps involved in diagnosing and treating PTSD: screening, official diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.

How is PTSD Treated?

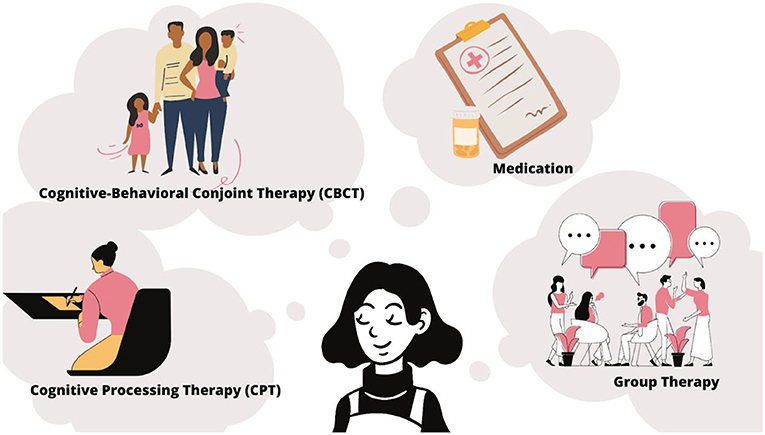

PTSD treatments can include medications, individual therapy, or group therapy (Figure 3). In therapy sessions, people typically participate in specific types of therapy called cognitive processing therapy (CPT) or cognitive behavioral conjoint therapy (CBCT). In CPT, people write about how their experiences have impacted their lives. The therapist helps patients pinpoint negative feelings and refocus their thoughts on the positive [2]. CBCT focuses on improving relationships by having patients work with their loved ones to improve problem-solving skills [1]. The other form of PTSD treatment is medication, which requires less time and effort from the patient, but must be taken under the watch of a healthcare team. Several medications used to treat PTSD are classified as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are drugs commonly used to treat depression and PTSD. SSRIs have been shown to improve mood and decrease anxiety [4]. Unfortunately, there is currently no definite cure for PTSD. People living with PTSD might manage their symptoms by continuing medication and/or therapy, seeking family counseling, and consciously avoiding triggers.

- Figure 3 - There are several types of treatment for PTSD.

- Examples include kinds of therapy called cognitive processing therapy, cognitive-behavioral conjoint therapy, and group therapy, as well as medications.

Triggers and Trigger Warnings

To keep PTSD in check, people with this disorder should try to avoid or mentally prepare themselves for situations that remind them of their traumatic event, known as triggers. In PTSD, a trigger sets off the stress response by reminding the person of the traumatic event, and can worsen PTSD symptoms. For example, violent movies with a lot of fighting can be triggering for a soldier who experienced war. Trigger warnings can help people avoid such triggers. Trigger warnings are notifications that warn people about potentially triggering types of content. They can be used at the beginning of certain movies, TV shows, or even TikToks. Trigger warnings allow people with and without PTSD to prepare themselves for the traumatic content, which can make viewing the trigger less shocking.

However, it is difficult to decide what should come with a trigger warning [5]. Take, for example, two movies that both feature soldiers in combat but have different titles. Should the movie with a clearly upsetting title, such as “Soldiers at War” or the one with a less obvious title, such as “Survival,” come with a warning? The audience must also be considered. A book with triggering content might be popular in one country but unpopular in another. As a result, teachers in the first country may assume that their students with PTSD have heard of the book and decide not to provide a trigger warning. Teachers in the second country may assume that their students with PTSD have not heard of the book and provide the warning. For these reasons, psychologists and disability advocates are coming up with more universal ideas of what needs a trigger warning.

PTSD is an Invisible Disability

Disabilities can fall under two main groups: invisible and visible. Visible disabilities, as the name suggests, are those you can see. For example, someone whose legs are paralyzed might have trouble moving normally and will need a wheelchair to get around. Invisible disabilities like PTSD are different, because you cannot tell whether a person has one just by looking at them. As a result, others may not realize that people with PTSD are different and may need certain types of help in daily life when compared to people without PTSD. For example, a boss might have two employees with PTSD but only “see” symptoms in one of them. The employee with the more visible PTSD may be allowed to leave work early each day to attend therapy, while the employee with the less visible PTSD must work as many hours as everyone else. The employee with invisible PTSD may have trouble focusing at work or finding time to attend therapy [6]. Moreover, if something is out of sight, it is often out of mind. Unfortunately, this means that PTSD often receives less attention from scientists and health care providers than many visible disabilities do. All of this tells us that, even though we cannot see invisible disabilities, it is important to remember that the experiences of people who have them are just as valid as the experiences of people with visible disabilities.

Conclusion

PTSD is a disorder that people may develop because of their past experiences. It can cause changes in mood, emotions, and interactions with friends and family. A person experiencing these changes can be affected by others’ opinions about the disorder, causing them to feel ashamed or uncomfortable. This can cause PTSD sufferers to hide their condition, attempting to be seen as “normal.” Pretending not to have PTSD can lead to depression, anxiety, and other mental illnesses [6]. Therefore, it is important to be kind and respectful toward those with disabilities, visible or invisible. By treating people with PTSD fairly, we can make them comfortable enough to be themselves and speak openly about their disabilities. Ultimately, this will lead to a better understanding of PTSD and its effects, which can help increase awareness of invisible disabilities and ensure better lives for those affected.

Glossary

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): ↑ A mental health condition that develops after a distressing event and results in variable symptoms that impact an individual’s life and relationships.

Trauma: ↑ A deeply distressing or disturbing event that may result in physical or psychological harm.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: ↑ A handbook that is used by healthcare professionals to guide the diagnosis of mental disorders.

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT): ↑ An individual works with a therapist to identify and refocus negative thoughts based on writing about lived experiences and their impact.

Cognitive Behavioral Conjoint Therapy (CBCT): ↑ A therapist helps an individual strengthen their relationships with others though improved problem-solving skills.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): ↑ A type of medication that increases levels of a chemical in the brain that positively affects mood and emotions.

Trigger: ↑ Events or circumstances that cause a person to recall a previous traumatic experience.

Invisible Disabilities: ↑ A type of condition that limits a person’s activities, but may not be visible to others based on their appearance; a person who uses a wheelchair has a visible disability, while a person with post-traumatic stress disorder has an invisible disability.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Monson, C. M., Taft, C. T., and Fredman, S. J. 2009. Military-related PTSD and intimate relationships: from description to theory-driven research and intervention development. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29:707–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.09.002

[2] ↑ Lancaster, C. L., Teeters, J. B., Gros, D. F., and Back, S. E. 2016. Posttraumatic stress disorder: overview of evidence-based assessment and treatment. J. Clin. Med. 5:105. doi: 10.3390/jcm5110105

[3] ↑ National Center for PTSD. 2018. Brief Trauma Questionnaire (BTQ). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; c1995-2007. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Available online at: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/brief_trauma_questionnaire_btq.asp (accessed May 6, 2020).

[4] ↑ National Center for PTSD. 2020. Medications for PTSD. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Available online at: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand_tx/meds_for_ptsd.asp (accessed May 6, 2020).

[5] ↑ Lockhart, E. 2016. Why trigger warnings are beneficial, perhaps even necessary. First Amend. Stud. 50:59–69. doi: 10.1080/21689725.2016.1232623

[6] ↑ Santuzzi, A., Waltz, P., Finkelstein, L., and Rupp, D. 2014. Invisible disabilities: unique challenges for employees and organizations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 7:204–19. doi: 10.1111/iops.12134