Abstract

What is the word for the sense of signals that come from inside your body, such as feeling your heart beating and your breathing, or knowing when you are hungry? This is called interoception. Interoception is one of our senses, like vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. In this article, we talk about what interoception is and how information about these feelings is sent from the body to the brain. We will also talk a little about how interoception is measured and the different types of interoception. Finally, we will discuss why interoception might be important for things like recognising emotions in ourselves and in other people, our physical and mental health, and why understanding how interoception changes throughout our lives might help us to understand where differences in interoception across different people come from.

What is Interoception?

Most of us have heard of the five basic senses, touch, smell, taste, sight, and hearing, but few of us know the term interoception. Interoception means sensing internal signals from your body, like when you are hungry, when your heart is beating fast, or when you need the toilet. You probably do not pay attention to these signals all the time, but if your teacher asks you to give a class presentation or you have just sprinted for the bus, you will probably feel your heart thumping in your chest. Parts of your brain are constantly tracking your internal signals to keep your body functioning properly and to notify you when something changes. For example, your brain might notice you are running low on water, prompting you to feel thirsty and grab a drink. Keeping the body in a balanced, neutral state is called homeostasis.

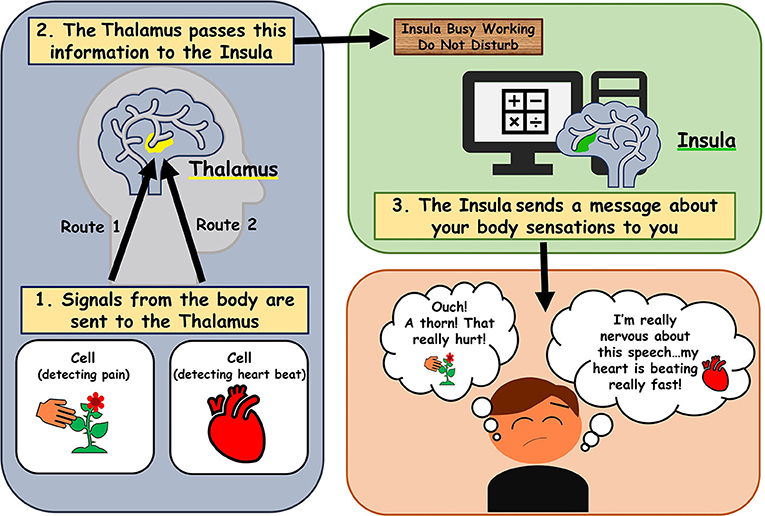

How do these signals from the body get to the brain? It depends on the signal we are talking about; some signals, like pain, are transferred via a slightly different pathway than other signals, like heartbeat. However, the signals travel to similar parts of the brain. In the middle of the pathway, they pass through a part of the brain called the thalamus which is a relay station that directs information to different parts of the brain. One key area that the information is sent to is the insula (Figure 1).

- Figure 1 - Simplified example of brain pathways involved in interoception.

- (1) Signals are detected by body cells. Some signals (like breathing or heartbeat) take a different pathway than other signals (like pain or temperature), but they all travel along nerve fibres and end up in a brain region called the thalamus. (2) The thalamus collects the signals and passes the information on to the final interoceptive brain area, called the insula. (3) The insula brings the message into conscious awareness, which makes the person aware of feeling hungry/hot/tired etc. (figure adapted from [1]).

Whilst homeostasis mostly operates outside conscious awareness, meaning we do not notice it is happening, we can pay attention to internal signals, so that we notice them consciously. Try to feel your heartbeat without using your hands. Is it easy or difficult to feel your heart beating? Now think about how often you notice your heart beating. In your everyday life, do you notice your heart beating often, hardly ever, or somewhere in the middle?

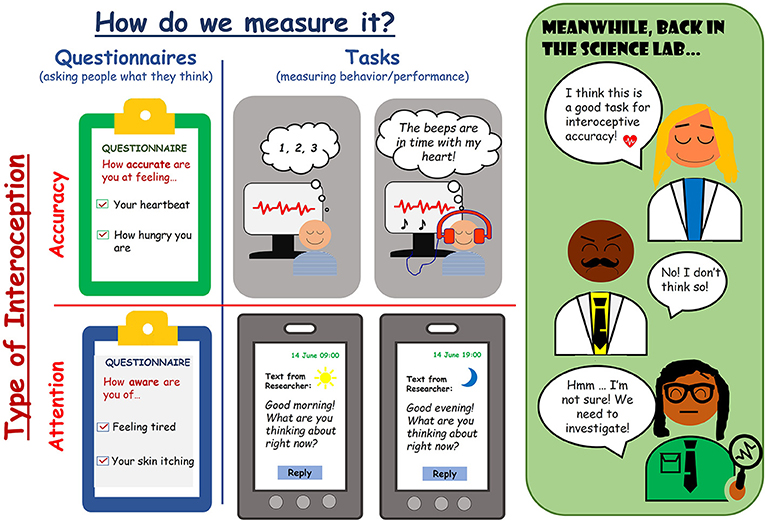

Did you notice that those questions asked you about different things? The first asked you how good you are at feeling your heart beating. This is called interoceptive accuracy. The second asked you how often you notice your heart beating. We call this interoceptive attention. Check out ways we might test people’s interoception in Figure 2.

- Figure 2 - How do we measure the types of interoception?

- Interoceptive attention and accuracy can be measured using questionnaires. However, some people find it hard to answer these questions. We can also measure interoception with tasks. To measure accuracy, we might ask you to count your heartbeats or tell us if beeps are in time with your heartbeat. To measure attention, we might send text messages to your phone at different times during the day, to ask you which body signals you are thinking about! Interoception is tricky to measure, partly because scientists do not always know what is happening inside your body. Scientists sometimes disagree on the best tasks to use or whether the tasks are good or not (figure adapted from [2]).

Individual Differences in Interoception

Now that you know about interoceptive accuracy, interoceptive attention, and some ways we might measure them, think back to the questions we asked you. How easy is it to feel your heart beating? How often do you notice your heart beating? You might be surprised to know that there are large individual differences in people’s answers to these questions and their performance on interoception tasks—this means everyone is different. What is interesting to psychologists is the impact of these individual differences on behaviour, health, and well-being.

There are many ways individuals can differ on the measures of interoception we talked about in Figure 2. For example, your friend might be more accurate at feeling body signals than you, but you might pay more attention to your bodily signals than your friend does. Whilst psychologists may disagree on how to measure individual differences in interoception, most would agree that these differences might have important consequences.

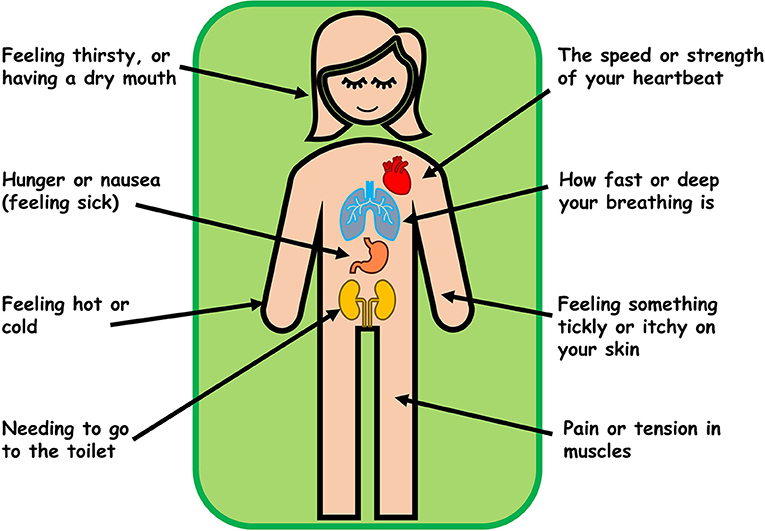

Some consequences are not that surprising. For example, if you have difficulties sensing stomach signals, you might eat or drink too much or too little. What if you have difficulty sensing pain signals? You might only realise you have hurt yourself when you receive information from another sense, like vision, when you see a bruise appear. This might make it harder for you to avoid getting hurt. Look at Figure 3 and think about these sensations. What might happen if we struggle to feel specific signals properly?

- Figure 3 - Examples of interoceptive sensations in our bodies.

- Look at the sensations inside the figure. What might happen if we struggle to feel these signals or if we pay too much or too little attention to them? We think individual differences in interoceptive attention and accuracy have different effects. Why? Some people may pay lots of attention to internal signals but find it difficult to accurately sense them. For example, some people may always feel they need the toilet, but may not actually need it when they think they do. Other people may pay little attention to internal signals in their day-to-day lives, but be very accurate at feeling them during an experiment.

Interoception, Emotions, and Decision-Making

Research suggests that individual differences in interoception may also affect behaviour that we might not expect, such as emotional experience and decision-making.

How do we know if we are happy, sad, angry, or disgusted? When we experience an emotion, it is usually accompanied by a change in the body, like heart rate or breathing. However, your heart beating fast could mean many things—you might be scared, excited, or have just run up the stairs! Most psychologists would agree that we act like detectives and gather information from the world around us to work out which emotion we are experiencing. If your heart is beating fast and you are about to give a class presentation, you might say you feel scared or nervous, whereas if your heart is beating fast and your football team is about to win a game, you might say you feel excited. Even though you use other clues too, the ability to sense internal signals is an important part of your emotional experience. Research supports this idea: people who find it difficult to sense internal signals often struggle to work out which emotion they are experiencing and have difficulties recognising emotions in other people. In contrast, people who find it easy to sense internal signals may experience emotions more intensely [3].

Interoception may also help with decision-making, especially when we are unsure what is the right decision is. One study found that people who were good at feeling their hearts beating did better on a task in which the aim was to win money and avoid losing money [4]. Why could this be? One idea is that the brain remembers which sensations happened (like a change in heartbeat) when a decision had a good outcome (like winning money) and when it had a bad outcome (like losing money). This helps us learn which decisions are best, even though these sensations are usually outside our conscious awareness. This is what people usually mean when they say, “I went with my gut instinct.” Individual differences in interoception might mean that some people use interoceptive signals to help with decision-making, whereas other people use information from outside the body, like the environment or other people, instead.

Interoception and Well-Being

Individual differences in interoception may be important for well-being [5]. For example, research suggests that people who are anxious pay more attention to internal signals. Because they pay extra attention to their heartbeat, something like a class presentation might be scarier for anxious people. Anxious people may also notice their hearts beating quickly in situations that others would not normally consider scary or worrying, like going to a party with friends. People without anxiety might think their hearts are beating fast because they are excited about the party. But, for somebody anxious, a racing heartbeat might make them think there is something to be afraid of.

In contrast, people who feel depressed may struggle with interoceptive accuracy. For example, people with depression often eat more or less than usual, maybe because they find it hard to tell whether they are hungry or full. Sometimes depressed people stop enjoying things they usually enjoy, which may be because they struggle to feel internal signals associated with positive emotions. If you had just won a prize, would you feel happy if you could not feel your heart beating faster? There are still lots of questions about how interoception is related to well-being that scientists are trying to answer!

Interoception Across Development

Scientists do not know why some people find it easy to sense internal signals while others find it difficult. One way of understanding where individual differences come from is to study interoception in people of different ages. Individual differences are present even in very young children; some children find sensing their bodies easy and others find it hard, and interoception may get harder for some people during adolescence [3]. However, interoception might not have the same impact in children and adults. Whilst adults with good interoceptive accuracy might be better at recognising emotions in other people, this may not be true for children. It is important for scientists to keep investigating interoception in people of all ages so we can understand how individual differences develop, and whether we can help some people improve their interoceptive abilities.

Conclusion

We know a lot about how people process information from outside the body using sight or hearing, but there are lots of questions about how we process information from inside our bodies, and how these signals affect behaviour, health, and well-being. For example, how does interoception change as we age, and why do some people find it easier than others? We are interested in how interoception may change across our lives, particularly during the teenage years, and whether these changes are important for our emotional abilities and well-being. It is important for everyone to understand what interoception is and why it is important! Just like our other senses, interoception might be important for our survival, emotions, decisions, and well-being. Whilst it is important to ask, “How am I feeling?”, we think it is just as important to ask, “What am I feeling?”

Glossary

Interoception: ↑ The process of sensing signals from the body, like heartbeat, breathing, hunger, or the need to go to the toilet.

Homeostasis: ↑ The process the body uses to maintain balance, for example by making us sweat to cool us down when we are too hot.

Thalamus: ↑ Part of the brain that receives signals from the body and passes the signals to different parts of the brain.

Insula: ↑ Part of the brain that responds to interoceptive and emotional signals. The insula looks like an island, and “insula” is the Latin word for island.

Conscious Awareness: ↑ A mental state in which we are aware of something.

Interoceptive Accuracy: ↑ A term that describes how good we are at feeling signals from the body.

Interoceptive Attention: ↑ A term that describes how much we notice signals from the body.

Individual Difference: ↑ Ways in which people might differ from each other. These could be things like intelligence, personality, or beliefs, as well as interoception.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Craig, A. D. 2002. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3:655–66. doi: 10.1038/nrn894

[2] ↑ Murphy, J., Catmur, C., and Bird, G. 2019. Classifying individual differences in interoception: implications for the measurement of interoceptive awareness. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 26:1467–71. doi: 10.3758/s13423-019-01632-7

[3] ↑ Murphy, J., Brewer, R., Catmur, C., and Bird, G. 2017. Interoception and psychopathology: a developmental neuroscience perspective. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 23:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2016.12.006

[4] ↑ Werner, N. S., Jung, K., Duschek, S., and Schandry, R. 2009. Enhanced cardiac perception is associated with benefits in decision-making. Psychophysiology 46:1123–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00855.x

[5] ↑ Khalsa, S. S., Adolphs, R., Cameron, O. G., Critchley, H. D., Davenport, P. W., Feinstein, J. S., et al. 2018. Interoception and mental health: a roadmap. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 3:501–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.12.004