Abstract

Do you know how to speak a foreign language? Learning another language is fun and useful! It can help you when you travel to other countries, and it might also help you talk with people in your own country who do not speak your language. If you have ever tried learning another language, you might know that it is not always easy. One difficult part is learning the grammar—the rules for how words are put together to form sentences. In our study, we researched how to make it easier for people to learn the grammar of foreign languages. And the good news? It is like riding a bike: the more you actively practice, the better you get at it. So, leave your grammar book in the classroom, and go out into the real world to practice!

Why Learn a Foreign Language?

Would you want to watch fireworks from the Eiffel Tower? Millions of people visit this exciting destination each year, but did you know that it is in France, a country that speaks a different language than English? In the United States, where we live and where some of you may be from, English is the most common spoken language. Many people in the United States also speak different languages, like Spanish.

In many countries, English is not the most spoken language. For example, most people in France speak French. So, if you are planning to go see the Eiffel Tower, it would be a good idea to learn some of the basics of French. That way, you will know how to speak with the locals that live there. Also, when you learn a foreign language, you can better appreciate music and movies in that language. Learning a foreign language opens up many possibilities for making new friends and learning about other cultures.

What Is It Like to Learn a Foreign Language?

Different languages have different words for things—for example, in French, to say “the cat,” you would say “le chat” (sounds like: luh shah). One of the first things to learn in a new language is the words, also called the vocabulary of the foreign language. That takes a lot of memorizing, since you need a lot of words to hold a conversation!

Of course, just learning new words is not enough to speak a new language. Different languages also have different grammar (rules for how words are put together to form a sentence). Figure 1 shows an example of a grammar difference between English on the one hand and French and Spanish on the other hand. Most people who try to learn a new language are pretty good at memorizing vocabulary, but have trouble learning the grammar.

- Figure 1 - The same sentence in Spanish, French, and English.

- The three languages have different vocabularies (for example, “gato,” “chat,” and “cat” mean the same). They also have different grammar, which you can see in the word order—take “orange cat” as an example. The word for the color orange comes before “cat” in English but after “gato” and “chat” in Spanish and French.

How Can We Make Learning Grammar Easier?

Because grammar is so difficult for people that are learning a foreign language, we tried to find ways to help people learn grammar. We first thought about how people can become good at memorizing vocabulary. Do you still remember how to say “the cat” in French? Take a second and see if you can come up with it without looking back at the example!

So? Do you remember what “the cat” is in French? If you guessed “le chat,” you would be right! Unless you already speak French, this was probably a difficult question. The reason it is difficult is because we asked you to come up with the word in a foreign language. For most of you, who are familiar enough with English to be able to read this article, it would have been easier if we had asked it the other way around—asking you what the French words “le chat” mean in English or another language you know. This is easier because you do not have to come up with the French words, since they are right in front of you. So why did we give you the more difficult question? Because studies have shown [1] that when you have to come up with a word from memory yourself, you will remember it better later.

The easy question (what does “le chat” mean in English) is an example of a language comprehension question—a question that tests your understanding. The more difficult question (can you say “the cat” in French) is an example of a language production question. Production means speaking, and speaking is usually more difficult than understanding, because it forces you to come up with the word from memory.

We wanted to know if speaking a language also helps you learn the grammar better. Because production questions make you work harder than comprehension questions do, we wondered if production training could help people learn grammar better than comprehension training. We will tell you about an experiment we designed to answer these questions, and for that, we will take you to outer space!

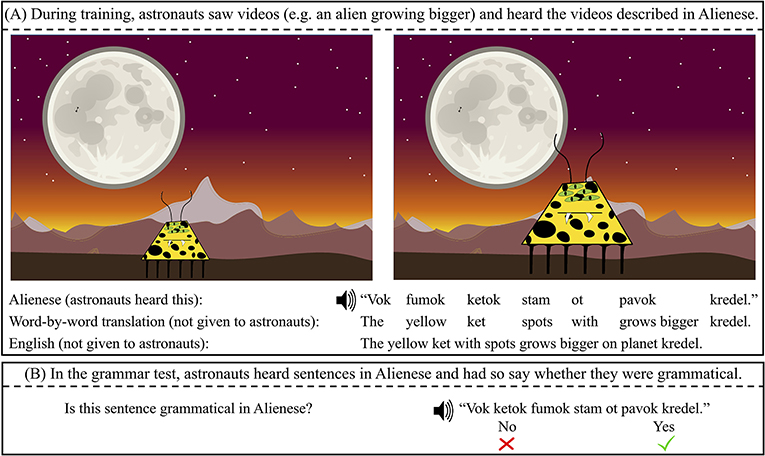

Why are we taking you to outer space for a language experiment? In our experiment, we used a made-up language called “Alienese” that only aliens speak. We asked about 100 English speaking college students to pretend to be astronauts and learn some Alienese. As you can see in Figure 2A, the aliens lived on cool planets!

- Figure 2 - (A) Two pictures from a video that astronauts were shown to learn about the aliens and their language.

- Astronauts had to learn the aliens’ names, the words to describe them (like yellow, spots), and the names of the planets—all in Alienese! (B) An example grammar test question. This Alienese sentence has an error, can you spot it? Compare this sentence with the one in (A) to help you. The grammar error in this sentence is in the word order. The word “fumok,” which means “yellow,” should come before the word “ketok,” not after it. This figure has been adapted from Hopman and MacDonald [2].

You might be wondering why we taught people a made-up alien language. That is because we wanted to compare how well people learn the language, and that would not be fair if some people already knew some of the words in that language. The only way to be completely sure no one knew anything about the language was to invent a new one ourselves.

Alienese has different grammar rules than English. One difference is in word order. In English, you say “with spots,” but in the alien language the words are the other way around. “Stam ot” is “spots with,” so “ot” (with), comes after the spots instead of before.

How Did We Teach People Our Alien Language?

First, all astronauts were taught the basics of Alienese. In this part, all they had to do was look at aliens on a computer screen while they heard words in Alienese. The next part is where things changed: the astronauts were now split into two groups.

Some of the astronauts were given comprehension exercises, which means that their new lessons were mostly about trying to learn Alienese by listening and understanding, followed by choosing the right answer to a question about the language on the screen.

The other group of astronauts tried something different—they had to try to speak Alienese. These astronauts were in the production group. They were trying to learn the language by speaking it, even though they just started learning it!

It might seem crazy to ask people to practice something they know very little about. But you might do this yourself without even knowing it! For example, to learn to ride a bike, we do not read books on how to do it (comprehension), we hop on a bike and start practicing (production). That is what is being tested in the production group—learning the grammar of a new language with hands-on learning.

At the end of the experiment, all astronauts had to take a final grammar test. Figure 2B shows one example of a grammar question from this test. The two groups took the same test so that we could compare them.

What Did We Find?

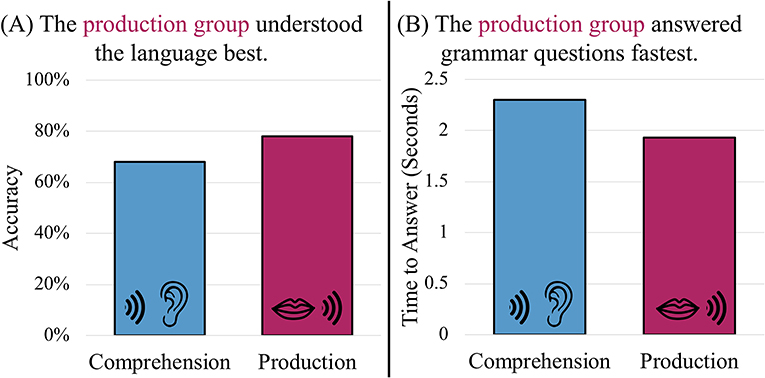

What do you think happened? Do you think the production group scored better on the grammar test than the comprehension group? If you said yes, you were right! Figure 3 shows that the production group not only got more answers right on the grammar test, but they also answered questions faster! Just by trying to speak Alienese out loud, the production group already became better at Alienese grammar than the comprehension group. This might seem weird as these astronauts did not even know all of the words and rules of Alienese perfectly, but speaking a language they did not completely know yet helped them more than just listening to it.

- Figure 3 - Our findings.

- (A) On the left, we show what percentage of grammar questions each group answered correctly, this is called accuracy. Do you see that astronauts in the production group (pink) answered more questions right than astronauts in the comprehension group (blue)? (B) The average time to answer each grammar question is called the Time to Answer and is shown on the right. You can see that astronauts in the production group (pink) needed less time to answer grammar test questions than astronauts in the comprehension group (blue). So, the production group was faster! This figure is adapted from Hopman and MacDonald [2].

Why Is Production So Helpful?

Some things, like learning a language and riding a bike, can be quite tricky—just practicing can be difficult. We think that having to work hard while practicing can be helpful for learning in the long run. Other researchers have studied how the brain responds when learning foreign language vocabulary [3]. They looked at parts of the brain that are used when people think very hard. The researchers found that these brain areas were more active during a difficult task, like our production task, than during an easier task, like our comprehension task. They also found that a production task was better than a comprehension task at strengthening memory in the brain for the foreign language.

Of course, we tested both grammar learning and vocabulary learning together—not just vocabulary learning—and we can only guess what was happening in the brains of our astronauts. We think that our astronauts learned more when they spoke the language, partly because their brains were working harder. Our experiment is good news for students though, because it shows us that even though we might not know how to speak Alienese or do wheelies with our new bike, we can learn by just trying. Yay for hands-on learning!

Can You Also Learn a New Language?

YES! If you decide to learn a new language, you now know something important: speaking in a new language helps us learn that new language faster than just listening to it. We need to practice a language by speaking it. That may be hard work for you and your brain, but it is worth it, especially if you make it fun. Learning a new language allows you to talk to more people around the world, and even within your own country. Some studies even show that being bilingual has many benefits for your brain, like being faster at switching between different tasks [4–6].

Are you ready to go on a language learning adventure like our astronauts did? If so, there are some apps out there that are friendly for kids and allow you to practice speaking out loud. Ask your parents to help you find and download these apps so you can get started and become a language adventurer!

Author Contributions

EH and MM designed and conducted the original study. CR wrote the first draft of this manuscript under supervision of EH. CR and EH created the figures and edited the second draft of this manuscript. MM made suggestions throughout and read and approved the final manuscript.

Glossary

Foreign: ↑ Foreign (pronounced as “for-in”) means from a different country than your own. So, if, like us, you live in the United States, French is an example of a foreign language.

Vocabulary: ↑ The words of a language are called its vocabulary. Your vocabulary in English is the English words you know.

Grammar: ↑ The rules of a language that determine how words come together to make sentences.

Language Comprehension: ↑ Language comprehension means understanding language, so whenever you are reading or listening to language you are doing language comprehension.

Language Production: ↑ Language production means speaking a language, so whenever you are talking or writing a language you are doing language production.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Misty Kabasa, Mark Koranda, Ethan Seidenberg, Rubiarbriana Jamison, and Zoe Hansen for comments on the drafts of this paper. We would also like to thank all parents, teachers, and kids from the Milwaukee French Immersion School who reached out to us with enthusiasm and feedback on this project.

Original Source Article

↑Hopman, E. W. M., and MacDonald, M. C. 2018. Production practice during language learning improves comprehension. Psychol. Sci. 29:961–71. doi: 10.1177/0956797618754486

References

[1] ↑ Karpicke, J. D., and Roediger, H. L. 2008. The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science 319:966–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1152408

[2] ↑ Hopman, E. W. M., and MacDonald, M. C. 2018. Production practice during language learning improves comprehension. Psychol. Sci. 29:961–71. doi: 10.1177/0956797618754486

[3] ↑ van den Broek, G. S. E., Takashima, A., Segers, E., Fernández, G., and Verhoeven, L. 2013. Neural correlates of testing effects in vocabulary learning. Neuroimage 78:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.071

[4] ↑ Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I., and Luk, G. 2012. Bilingualism: consequences for mind and brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16:240–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.03.001

[5] ↑ Marian, V., and Shook, A. 2012. The cognitive benefits of being bilingual. Cerebrum 2012:13. Available online at: https://www.dana.org/article/the-cognitive-benefits-of-being-bilingual/

[6] ↑ Costa, A., Hernández, M., and Sebastián-Gallés, N. 2008. Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: evidence from the ANT task. Cognition 106:59–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.013