Abstract

People think that helping others is nice. Teachers and parents often tell children to help others, for example in the classroom. I discovered that sometimes children help in a way that is not nice. In two studies, children (7–9 years old) got to help peers solve puzzles. Children gave more correct answers to someone who was struggling with the puzzles, but they gave more hints to someone who was already good at the puzzles. If you simply give someone the answers, they cannot learn new skills—and people who do not learn new skills can keep struggling. Children in my studies thus helped their struggling peers in a way that causes them to keep struggling, while the way they helped the peers who could already solve the puzzles made these children become even better at them. Thus, sometimes help can lead to outcomes that are not so positive.

Different Types of Help

We often help others because we care about them, or we see that they need help. We frequently help others because we think it is a nice thing to do. But is helping always nice? In my research, I discovered that sometimes the help that children provide to peers can be harmful [1].

Not all help is the same [2]. Imagine that you are doing a word puzzle that you like and are good at, and one of your classmates asks you for help on the same puzzle. How will you help them? You could decide to give your classmate a hint. This is often called indirect help. It is indirect because such help allows your classmate to learn to figure out the answers on their own. Maybe the next time they work on a similar puzzle they will not need help because they now know how to solve it.

But you could also decide to help by simply giving your classmate the correct answer. This is called direct help. Direct help will make doing the word puzzle easier for your classmate, of course, but it also takes away their opportunity to learn something new or figure the puzzle out by themselves. And when they do a similar word puzzle again, they will still need help because they did not learn how to solve it on their own.

Which type of help do you think is better? In most cases it is probably better to give indirect help, especially because it actually helps others learn more in the long run. After all, indirect help teaches others to become better at something, so the next time they do the task they will not need as much help. It is like an old saying you might have heard: “give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime”.

How Do Children Help?

How do children help others? Do they give more indirect help or direct help when they are helping their peers? I tested this with children who were 7–9 years old, by conducting two similar experiments in the Netherlands. In the first experiment I tested 80 children (63.7% boys, 36.3% girls, 75% of the children were native Dutch), and in the second experiment I tested 41 children (61% boys, 39% girls, 80.5% were native Dutch). Children participated in the experiments at school, at their after-school daycare, when visiting a science museum, or at home. Children were always tested in a quiet room, and they sat in front of a computer. I told the children they were going to be quizmasters and were supposed to help two peers who were taking a quiz. They saw these children on the computer screen (Figure 1). In reality, these peers were not actually there, but the children believed that they were (and afterwards we told them this was not true).

- Figure 1 - In my experiments, children sat in front of a computer screen and were told that they should act as “quizmasters”, helping their peers (visible on the screen) who were taking the quiz.

- The quizmaster children could either give indirect help (orange button) or direct help (blue button).

The children then listened to these peers receiving instructions on how to take the quiz. We recorded these messages beforehand. In this message the experimenter also told the children how their peers did on another quiz they took earlier. To one peer, the experimenter said: “I heard you did not do so well last time, you answered a lot of questions incorrectly, right?”. To the other peer, the experimenter said: “I heard you did really well last time and answered a lot of questions correct, right?”. The children we were testing overheard these remarks so they could form an impression of each peers’ competence at the quiz. We wanted the children to think that one peer was good at the quiz and the other one was not. This way, we could test if children give different types of help when they think others are good at something or struggle with it. And they did!

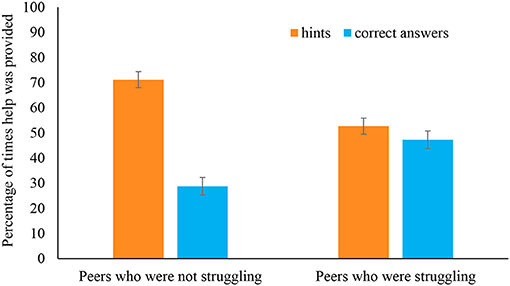

In both studies, children gave more hints (indirect help) to peers who were competent, and they gave more correct answers (direct help) to peers that were not competent (Figure 2). In the first study, the peers worked on puzzles, and in the second study, the peers worked on a math quiz. The children gave more direct help to peers that were not competent even when we told them the peers needed to practice their skills for the final round. So, children knew it was important for all children to learn how to do the quiz. Yet, they made peers who already did well practice more than children who struggled. Children’s gender did not influence the results, meaning boys and girls both provided more indirect help to peers who did not struggle and more direct help to peers who struggled.

- Figure 2 - When their peers were not struggling with quiz, the helping children provided hints 71.2% of the time and only gave their peers the correct answers 28.8% of the time.

- However, when their peers were struggling, the kind of help the children gave changed. They provide hints only 52.7% of the time and they gave the correct answers 47.3% of the time. This means that children were more likely to give direct help to struggling peers than to non-struggling peers.

Overall, the results showed that when children think others struggle, they are more likely to give them direct help. However, this means that those peers do not learn new skills. So, if the peers were not good at the task to start with, they could not get better from the help they received. Giving indirect help to already competent peers means these peers can get even better at the task because they practice even more.

Does It Matter How Children Help?

So, if children help this way, what happens in the end? The children who do well get better, and the children who struggle keep struggling. This also means that the difference in competence between struggling and non-struggling children gets bigger.

That is not all. When some children get more direct help, it might also make them feel worse about themselves. They might think that others do not have confidence in their ability to solve challenges on their own. Feeling bad about how well they do at school tasks can make kids less motivated to do schoolwork and can make them feel unhappy.

One more reason that the type of help matters is that others in the classroom might also start thinking differently about the children who get more direct help [3, 4]. We know this because we also asked children what they think it means when others get direct help or indirect help. Our data showed that children think peers who get more direct help are less smart. So, if some children receive more direct help, their classmates might start to think less positively about them.

In summary, it matters a great deal how children help peers. When children give more direct help to peers who they think struggle, these peers do not improve their skills, might feel badly about themselves, and others might think they are less smart. This can set up a negative cycle—when children think others are less smart, and they may again give them more direct help!

More research is needed, however. Children in my studies, for example, did not actually see or know the children they helped, and all the children were living in the Netherlands and were 7–9 years of age. It would be interesting to go to real classrooms in different parts of the world to observe how children of different ages help their classmates. Perhaps all children help classmates who struggle differently from classmates they think do not struggle. But maybe children’s helping is influenced by whether they are friends with the classmates or not. Or maybe children help others differently because they live in cultures where teachers or parents often provide direct help, so they think that is the best helping strategy.

Solutions

So, what can we do about this? Many people think helping others is always nice and we should all do it. But if you look more closely, you see that this is not always the case. We could make sure teachers know about how helping can lead to negative effects. Then maybe teachers can make sure that if they assign children to help each other, they also look at how they help and make sure it does not lead to bad outcomes for some children. Another solution is to teach children about the different types of help and make sure they help in ways that are not harmful. That is why I wrote this article—the next time you offer to help someone, I hope you remember to make sure to give them the right kind of help!

Glossary

Peers: ↑ Refers to a person that is of the same age (a classmate, for example).

Indirect Help: ↑ The sort of help that helps others figure something out themselves. For example, when someone is doing a puzzle, you could give them a hint to help them solve it.

Direct Help: ↑ The sort of help that provides an immediate solution to the problem, such as giving someone the correct answer to a test question.

Competence: ↑ How good you are at something.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

JS was supported by an NWO Talent Programme Veni Grant (VI.Veni.191G.052).

Original Source Article

↑Sierksma, J. 2023. Children perpetuate competence-based inequality when they help peers. NPJ Sci. Learn. 8:41. doi: 10.1038/s41539-023-00192-9

References

[1] ↑ Sierksma, J. 2023. Children perpetuate competence-based inequality when they help peers. NPJ Sci. Learn. 8:41. doi: 10.1038/s41539-023-00192-9

[2] ↑ Nadler, A., and Chernyak-Hai, L. 2014. Helping them stay where they are: status effects on dependency/autonomy-oriented helping. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 106:58–72. doi: 10.1037/a0034152

[3] ↑ Sierksma, J., and Shutts, K. 2020. When helping hurts: children think groups that receive help are less smart. Child Dev. 91:715–23. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13351

[4] ↑ Graham, S., and Barker, G. P. 1990. The down side of help: an attributional-developmental analysis of helping behavior as a low-ability cue. J. Educ. Psychol. 82:7–14.