Abstract

“Climate Justice, Now!” is a banner you often see at climate protests. But what is climate justice? Changes in Earth’s climate impact the whole world, but the impacts are much harsher for some people, particularly poor communities, Indigenous and disadvantaged minorities, young people, and future generations. Importantly, the people who face the most serious impacts of climate change are often those who have contributed the least to the causes of climate change. In this article, we consider why the impacts of climate change are unfair and discuss some ways that we can help reduce this unfairness to bring about climate justice now.

Why is Climate Change Unfair?

While our changing climate effects everyone, the disruptions to everyday weather caused by the warming of the atmosphere are unfair because the most serious impacts are often experienced by people who have done the least to cause climate change and who have the fewest economic resources to protect themselves. Around the world, the people who are most at risk in a changing climate are often the poorest in any community. They may rely on the natural world for their livelihoods, or they may suffer disadvantages that make them more likely to lose everything in a major weather event. For example, if you live in a neighborhood that is likely to flood but your family does not have money to move away, you are at greater risk than people who can afford to buy a new house in a safer place or buy insurance to rebuild their homes.

People living on small islands in the Pacific produce a very small amount of the carbon emissions that drive climate change, but they are exposed to serious climate risks including destruction of the coastline (erosion), cyclones, and rising tides that threaten their homes. Even their community identity and history are at risk—for example, when storms erode the burial sites of village elders. However, for people living in large cities who already have the money and resources to protect their homes, the effect of a changing climate might simply mean longer and hotter summers or disruptions to their travel and work plans; but these disruptions do not cause serious risks to their lifestyles [1].

The impacts of climate change are not experienced in the same way by everyone around the world. The impacts of severe storms, droughts, wildfires, heatwaves, or floods are worse for the world’s poorest people, including children living in rural communities, informal settlements, islands, or places where people rely on stable weather to grow their food [2]. These areas include parts of Africa, Asia, South and Latin America, the Pacific, and the Arctic. Climate risks are also more serious for older people who live alone, people who have been impacted by war, or new migrants who do not have access to health care or a network of friends and neighbors they can call on for support. Even within a country, some groups of people are at a higher risk, including for example, children in low-income rural communities and older people who are poor and have few friends or family nearby to help them in storms or heat waves [2].

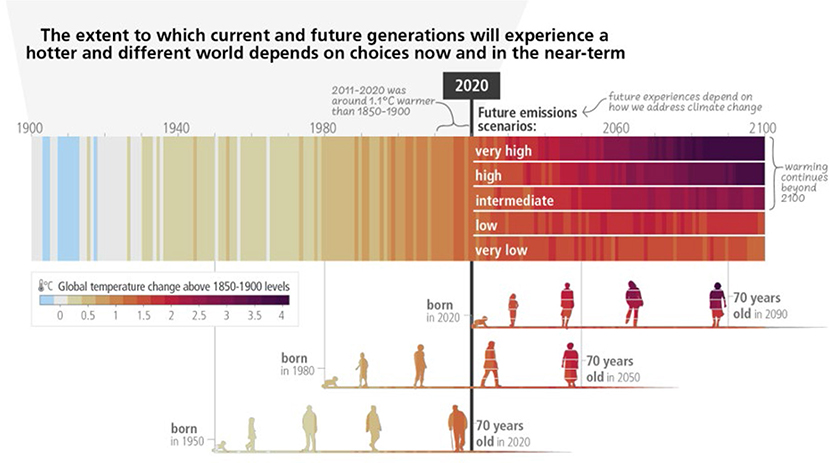

Beyond impacting people differently in different places, if we do not take action now, climate change will have more serious impacts for very young children and people who are not yet born, because a bigger part of their lifetimes will be affected by our changing climate (Figure 1) [3]. Climate change is experienced unfairly across generations because babies born in 2020 will experience many more climate risks as they grow up than any generation before them—but we can change this if we take action on climate risks today.

- Figure 1 - Unless we take action to help Earth’s climate now, babies who were born in 2020 will face a much hotter world and more serious climate impacts than their parents and grandparents did.

- The figure shows how the climate has changed since 1900. Each year has a colored bar that reflects the world’s temperature for that year. Blue years are cooler than average and red years warmer than average. The figure shows how the future might look too, and that children born in 2020 will experience climates that older people did not live through (Source: [3]).

In 2023, the United Nations (UN) declared that climate change was affecting human rights, especially the rights of children to live in a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment and the right to be protected from the impacts of a changing climate. One reason the UN took this action was because 16,000 children from 121 countries wrote to them to demand a fairer future. In 2024, the UN went a step further and agreed that climate change also affects the rights of future generations. The UN called this a Pact for the Future and it asked all countries to act to protect today’s children’s rights, including rights of children who are not yet born, and the future of the planet.

What is Climate Justice?

When we talk about climate justice we mean acting fairly, noticing how people are differently impacted by climate change, and working together to address climate problems in ways that treat everyone with respect. Climate justice means we do not discriminate against people based on how much money they have or what their religion or culture is, for example. But because the climate impacts different people in different ways, we cannot just treat everyone equally or the same. To be fair also means we need to think about equity. That means understanding how different people face different challenges and risks, and what kinds of resources and support they might need to cope in a changing climate.

Four Principles for Climate Justice

Acting to bring about climate justice involves thinking about four big ideas [4].

Procedural Justice

The first idea is to make sure everyone impacted by climate change has a say in making decisions about climate change. This principle is called procedural justice. If a decision process is fair, people of all ages, communities, and religions can have a say when decisions are being made that impact their long-term future. This might mean that the whole community has a say in a government decision to continue to mine more coal, for example. Procedural justice also means that people whose lives and jobs will be impacted by any big changes are heard and their views are considered. People may not all agree, but taking time to listen to everyone’s ideas and experiences can improve decisions. In 2024, the Council of Europe recognized that many young people want to be heard in climate decision making but are often excluded and sometimes face legal threats when they protest about climate change. The Council called on all European governments to protect the rights of young people, particularly “young environmental defenders”, so that kids are free to protest and speak out about how the climate impacts the planet and their physical and mental wellbeing.

Distributional Justice

A second way we can improve climate justice is to ensure the good and bad effects of climate change, and the benefits from climate solutions, are experienced, shared, or distributed fairly among everyone. This is called distributional justice. Right now, we do not have distributional climate justice because vulnerable communities and people continue to face some of the most serious impacts of climate change, while rich countries and the richest individuals continue to benefit from using more than their fair share of fossil fuels and resources. For example, global data shows an average Indian citizen emits 1.9 tons of CO2 every year, while an average American citizen emits 14.9 tons, and a Ugandan emits 0.9 tons. As countries grow, the rich in every country consume much more than the poor do. To give you an idea of how severe this is, the richest 10% of the global population emits nearly half of the world’s carbon emissions, while the poorest half of the world only emits about 12%.

Distributive justice also means we need to think about fairer outcomes and who should pay to help communities who have suffered losses and damages—including loss of sacred places, crops, or access to education. For example, some countries have benefitted for a long time from using fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas. In 2024, a group of law students from the small Pacific nation of Vanuatu took a case to one of the highest courts in the world, the International Court of Justice. They asked what legal responsibilities governments have to prevent climate change from impacting small islands [5]. When some countries or groups of people face unfair risks caused by past and current actions of other countries (or companies), there are growing calls to compensate people for unfair losses and the damages they face.

Recognition Justice

A third principle of climate justice is recognition justice. Recognition justice means treating people with dignity, recognizing that different people have different needs based on their cultures, identities, and life experiences. For example, climate change can affect genders differently, so our solutions must be sensitive to these differences. Recognizing gender matters is important because women and girls are often faced with serious risks due to the kinds of jobs they may do in some communities. Collecting water is one example—when water is scarce, women and girls may have to walk longer distances, taking time away from other ways of earning a living or their education [6]. Yet women and girls can change their communities, particularly when they are recognized as having experiences, insights, and ideas that can help in decision making.

Intersectionality

People face unfair climate risks not only because of one thing, like their gender or whether they are rich or poor, but because of a combination of things like colonization, sexism, and racism, which can expose some people to even more serious harm. When we pay attention to these intersections of unfairness, it is easier to understand why some people and communities are exposed to greater risk from climate change [7]. For example, the impact of colonization on Indigenous people resulted in loss of land ownership, which has increased poverty and made it more likely that Indigenous communities might have to live in flood-prone areas where housing is cheaper. Being a member of an ethic minority or a member of a LGBTQIA+ community might make it doubly challenging for a person to have their voice heard and influence climate decisions, unless their human rights, like freedom of speech, are protected.

Climate Justice, Now!

In summary, if we want climate justice now, we need to pay attention to the complex and unequal ways that climate risks impact diverse groups of people around the world and over time. Climate justice means thinking carefully about who is most vulnerable to climate change and what makes them vulnerable. The idea of climate justice makes us pause and question why, as global warming increases, some people always seem to be winners, and some people are always losers. It then pushes us to think of steps to change this to make the future fairer for everyone—through listening carefully and respectfully to a wide range of views and taking thoughtful action to meet diverse needs. Climate justice is making the future fairer and more equitable for everyone.

Glossary

Climate: ↑ The long-term average pattern of weather conditions like temperature, rainfall, and wind over a period of months to years.

Weather: ↑ The short-term conditions of the atmosphere that can change from day to day. For example, is it rainy, cold and windy, hot and dry, or humid?

Equity: ↑ Making sure people are treated fairly by recognizing their different situations, and sharing climate impacts, responsibilities, and decisions across society, generations, and genders.

Procedural Justice: ↑ Making decisions in a fair and open way where everyone can have a say, even if they do not agree with the final result.

Distributional Justice: ↑ Where the good and bad effects of climate change, and the benefits from climate solutions, are experienced, shared, or distributed fairly among everyone.

Recognition Justice: ↑ Treating people with dignity, recognizing that different people have different needs based on their cultures, identities, and life experiences.

Indigenous People: ↑ Groups who differ from dominant societies, lived in a place before colonization, and have deep ties to their ancestral lands, unique cultures, languages, and traditions.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Gatiso, T., Greenhalgh, S., Korovulavula, I., Fong, T., and Radikedike, R. P. 2025. Understanding cultural losses and damages induced by climate change in the Pacific region: evidence from Fiji. Clim. Policy 1–17. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2025.2488989

[2] ↑ Birkmann, J., Liwenga, E., Pandey, R., Boyd, E., Djalante, R., Gemenne, F., et al. 2022. “Figure 8.6”, in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds. H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Tignor, A. Alegría, et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1171–274. doi: 10.1017/9781009325844.010

[3] ↑ IPCC. 2023. “Figure SPM.1: (C) summary for policymakers”, in Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds. Core Writing Team, H. Lee, and J. Romero (Geneva: IPCC), 7–8. doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001

[4] ↑ IPCC. 2022. “Summary for policymakers”, in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds. H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 3–33. doi: 10.1017/9781009325844

[5] ↑ Rikimani, B. M. 2024. Climate justice and Pacific Island countries – a case study on grassroots advocacy. Round Table 113:374–84. doi: 10.1080/00358533.2024.2382563

[6] ↑ Caretta, M. A., Mukherji, A., Arfanuzzaman, M., Betts, R. A., Gelfan, A., Hirabayashi, Y., et al. 2022. “Water”, in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds. H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 551–712. doi: 10.1017/9781009325844.006

[7] ↑ Amorim-Maia, A. T., Anguelovski, I., Chu, E., and Connolly, J. 2022. Intersectional climate justice: a conceptual pathway for bridging adaptation planning, transformative action, and social equity. Urban Clim. 41:101053. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2021.101053