Abstract

The character Dory from Finding Nemo has a memory problem. Poor Dory has a hard time remembering anything. She forgets who her family is and what has happened in her life. In just a couple of minutes, she forgets the things that her friends say to her. Movie makers are trying to show what amnesia, a type of memory loss, is like. However, real-life amnesia looks very different from how it appears in movies. We will talk about how hurting the hippocampus, a special, small part of the brain, can cause real-life amnesia. We will talk about how amnesia makes it extremely hard to learn and remember some kinds of information (facts, e.g., the rules of a video game), but not other kinds of information (skills, e.g., how to use a joystick). Finally, we will talk about the special people throughout history who have taught scientists the most about what amnesia is, what causes amnesia, and what can be done to help people who have amnesia.

Have you ever forgotten somebody’s name, even though you just met them? Or have you ever forgotten where you put something in your room? These types of difficulties remembering things are very common: they happen to all healthy people some of the time. But for some people, having a hard time remembering things happens almost all of the time. When people have a very severe problem learning and remembering new information, we say that they have amnesia.

The word amnesia is used frequently on TV and in the movies to talk about anyone who has a problem with memory. Dory, from Finding Nemo, is one of the most famous examples (Box 1). Some characters in TV shows or movies might wake up one morning and suddenly forget who they are and where they are from. Other times, a character is hit on the head and forgets everything that has happened to them in their life. These types of memory changes do not actually happen very often in real life. Real-life amnesia looks different than it does in the movies. Next, we will talk about what amnesia means in real life.

Box 1. Amnesia in the movies.

The character Dory from the movies Finding Nemo and Finding Dory is an example of a movie character who has amnesia, or memory loss. Some of the things that Dory does in the movies are a lot like real-life amnesia. For example, Dory forgets that she has met Marlin, another character in the movie. This is an example of anterograde amnesia. On the other hand, some of the things Dory does in the movies are not like real-life amnesia. Dory forgets many of her childhood memories. For example, she forgets who her parents are and how they became separated when Dory was a kid. Forgetting memories from childhood is not common in real-life amnesia. Dory also says she has “short-term memory loss.” This is another example of how the movies can get amnesia wrong. Dory does not have trouble holding onto information for a “short” time but rather has trouble getting information into her long-term memory to be remembered later.

What Causes Amnesia?

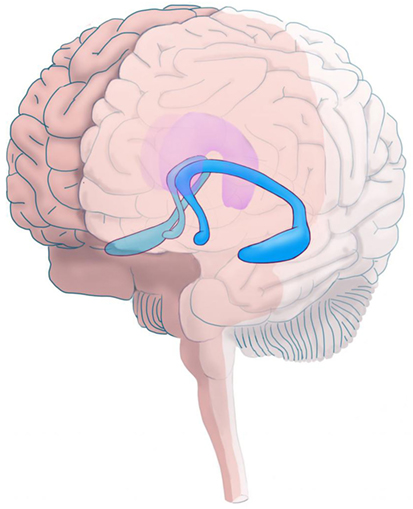

What causes real-life amnesia? Amnesia is usually caused by damage to a special part of the brain called the hippocampus. Every person has two of these: one on the right side of the brain, and one on the left. The hippocampus is pretty small—around 3.5 m3 (or 0.21 in3)—but it is a really important part of the brain (Figure 1). Damaging the hippocampus is the most common way to get amnesia, but damaging other brain areas that communicate with the hippocampus can also cause amnesia. In this study, we are going to focus on the hippocampus, because the role of the hippocampus in amnesia has been studied the most.

- Figure 1 - Location of the hippocampus in the brain.

- This picture shows where the hippocampus (in blue) is located in the brain. You have two hippocampi: one on the left side (dark blue) and one of the right side (light blue) of your brain. The hippocampus is very important for your ability to learn new facts and events (Credit: Jay Leek, UC Davis).

There are two ways that scientists talk about amnesia. First, amnesia can happen alongside other problems. For example, there are some diseases and injuries that can cause damage to the hippocampus and cause memory loss. These include Alzheimer’s disease and traumatic brain injury. Both of these conditions can cause memory loss, but they usually also cause other problems for a person’s ability to think. For example, a person with Alzheimer’s disease or traumatic brain injury might have difficulty planning for the day or making good decisions. So, when people with Alzheimer’s disease or traumatic brain injury have memory loss, we say that they have amnesia as one of their symptoms. People can have different degrees of amnesia as a symptom, from mild memory problems to severe memory problems. Having amnesia as part of a large set of problems is fairly common. But amnesia can also occur by itself, without other problems.

Amnesia by itself is very rare, because damage to just the hippocampus is very rare. A person can hurt his/her hippocampus by getting very sick with a disease called herpes simplex encephalitis, by having a brain surgery that removes part of the hippocampus, or by having an accident that keeps oxygen from getting to the hippocampus (Box 2). Luckily, these things do not happen very often. But if a person does damage the hippocampus, this usually causes the person to have memory problems. Interestingly, people who have amnesia have a hard time learning some kinds of information, but not other kinds of information. People who have amnesia are very rare, but they are very important for teaching doctors and scientists about how memory works and how scientists can help people with memory impairment to get better.

Box 2. Damage to the hippocampus.

One way that a person can get amnesia is after an incident that prevents oxygen from getting to the brain. This can happen as a result of a heart attack, very bad seizures, or a traumatic brain injury. When the brain is not getting enough oxygen, brain tissue starts to shrink (also called atrophy) and does not work well any more. The hippocampus is very sensitive to a lack of oxygen. This means that it atrophies faster than other parts of the brain when it does not have enough oxygen. Unfortunately, when the brain is injured, sometimes it does not heal the same way that skin heals when a person gets a scrape or a cut. Sometimes, the brain stays injured and atrophied and causes problems like amnesia.

Patients with Amnesia

Scientists have learned a lot about amnesia and different types of memory by studying people who have damaged the hippocampus. In the scientific literature, these people are often called “patients,” but it is important to remember that patients are people. The most famous patient with amnesia is known by his initials: H.M. Scientists use initials to protect the identity of patients when they write about them in scientific articles. We now know that this patient’s name was Henry Molaison. Henry Molaison was born in 1926. Mr. Molaison had seizures when he was a child, which means that his brain was not working normally. These seizures caused Mr. Molaison to have a very difficult life. To stop the seizures, a brain surgeon named Dr. William Scoville removed both of Mr. Molaison’s hippocampi [1]. Because this happened a long time ago, the surgeon was not completely sure what would happen. Scientists did not know what the hippocampus was important for yet, and Dr. Scoville thought he could help Mr. Molaison’s seizures by taking them out. A good thing that happened because of the surgery was that Mr. Molaison’s seizure disorder got better. But, unfortunately, removing both of Mr. Molaison’s hippocampi meant that he had a very severe memory problem. He had amnesia.

Amnesia made lots of things difficult for Mr. Molaison. But, Mr. Molaison also helped scientists learn a lot about the brain and about what the hippocampus does [2]. The scientists who worked with Mr. Molaison were the first to discover that the hippocampus was important for memory. While many different scientists worked with Mr. Molaison, two of the most famous were Brenda Milner and Suzanne Corkin. Before Mr. Molaison’s surgery, scientists thought that there was no specific part of the brain that was special for memory. After Mr. Molaison’s surgery, scientists learned that the hippocampus is special for memory—if you damage the hippocampus, you will have memory problems.

Other Cognitive Abilities

Another thing that Mr. Molaison’s surgery taught scientists was that damage to the hippocampus impacts only memory. After his surgery, Mr. Molaison had bad memory problems and was not able to form new memories for facts and events. You might think that Mr. Molaison would have many other problems besides this memory impairment, but this was not the case. After the surgery, Mr. Molaison was just as intelligent and able to problem-solve as he was before his surgery. He seemed to have normal thinking abilities and normal language ability. Mr. Molaison also had the same personality as he did before his surgery. These normal abilities were surprising to scientists, because many types of brain damage (like the kind that causes Alzheimer’s disease or traumatic brain injury) cause many problems at the same time.

Timing of Information

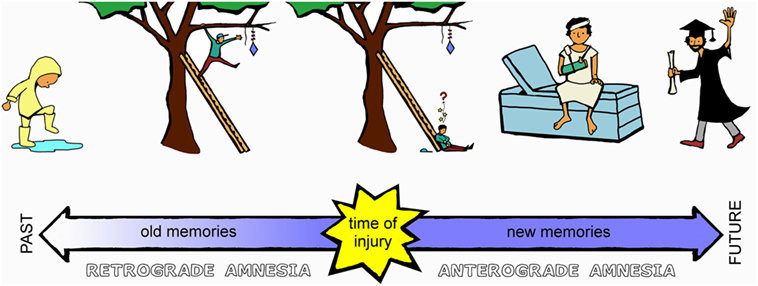

People who have amnesia have a very hard time learning and remembering new information. In real-life amnesia, it is not common for people to forget things about themselves or to forget things that have happened to them in the past. In general, people with amnesia have a hard time learning new information [3]. They have a hard time learning new things after they damage the hippocampus. This kind of amnesia has a specific name: anterograde amnesia (Figure 2). The things that they learned before they hurt the hippocampus are not usually hard for them to remember. This means that adults with amnesia can usually remember stories from when they were kids, even though they cannot remember what they ate for breakfast this morning. The scientists working with Mr. Molaison realized that he could remember things from when he was a kid, even though he could not remember working with them from day to day. So, even though Suzanne Corkin worked with Mr. Molaison for years, she needed to tell him her name each time she saw him: Mr. Molaison could not learn that information [4]. While people with amnesia can usually remember things from the long-ago past, they can forget some things that happened to them right before they damaged the hippocampus. Forgetting information from before damage to the hippocampus is called retrograde amnesia.

- Figure 2 - Anterograde and retrograde amnesia.

- People with amnesia have difficulty forming new memories. This is called anterograde amnesia. This means that a person with amnesia might have difficulty remembering things that happen to them after they are injured (like the time they spent in the hospital). While a person with anterograde amnesia would have a hard time remembering new information, he would probably not forget memories from when he was little. It is possible for a person with amnesia to forget some things from before the injury. This is called retrograde amnesia. Usually, the memories that are most likely to be forgotten are memories formed right before the person’s injury. So, the person in this picture might forget what he was doing right before he fell off the ladder (he might forget that he was trying to get a kite). But it is very unlikely that he would forget memories that he had from when he was a little kid.

Type of Information

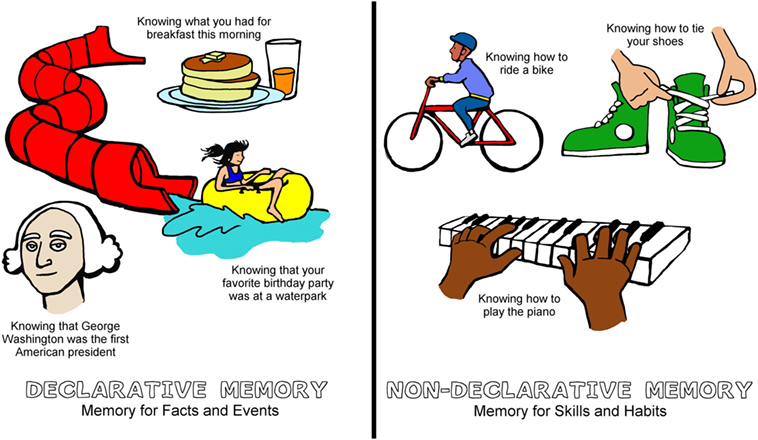

The timing of information is not the only thing that affects whether people with amnesia will have a problem learning things. The kind of information a person is trying to learn is also important. In particular, people with amnesia have a hard time remembering new facts and events. For example, a person with amnesia would have a hard time learning a new fact from a textbook at school. If the person did not already know that George Washington was the first president of the United States, it would not matter how many times you tried to tell them, they still would have a hard time remembering that fact. Also, a person with amnesia would have a very hard time remembering new events in their life. So, the person might take a walk with you in the park. An hour later, when you try to talk about the funny dog you saw at the park, the person with amnesia would not remember the dog you saw, or that you had taken a walk at all. Memories for facts and events are called declarative memories. People with amnesia have a specific problem with declarative memory.

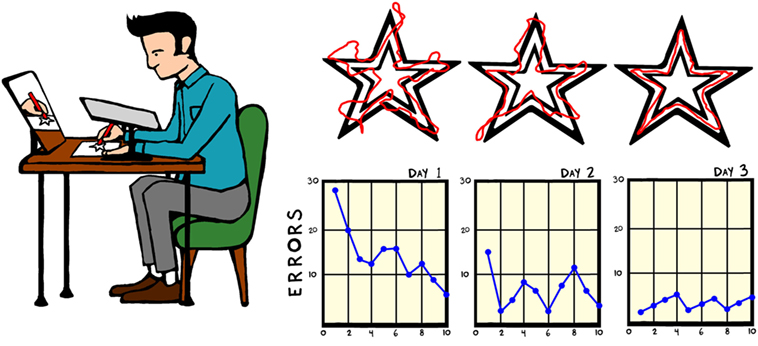

When scientists first discovered that damage to the hippocampus caused a person to be unable to learn new facts or remember new events, they thought that people with amnesia were unable to learn anything new. But, the scientists working with Mr. Molaison quickly discovered that people with amnesia can learn some kinds of new information [5]. The kinds of information that people with amnesia are able to learn are new skills and habits [6]. An example of how scientists discovered that people with amnesia are able to learn new skills is presented in Figure 3. So, a person with amnesia might learn how to sew or how to move a joystick to play a new video game. Memories for skills or habits are called non-declarative memories. People with amnesia generally do not have a problem with non-declarative memory. Figure 4 gives examples of declarative and non-declarative memory.

- Figure 3 - The mirror tracing experiment.

- One way scientists have learned that Henry could still learn new skills after his surgery was based on his performance on a mirror-tracing task. Here is how the experiment works: The research participant is asked to trace a star and stay between the lines. The tricky part is that the person cannot see their own hands—they have to look at their hand in a mirror instead. This makes tracing the star very hard. At first, people make a lot of errors. But tracing lots of stars makes a person better at it. The person learns a new skill. Healthy people get better and better at tracing the star each time they do it. The three stars show examples of how a person might get better over time. At first, the red line goes outside the black lines a lot. The next time, the red line goes outside of the black lines less often. The last time, the person is able to keep the red line inside the black lines all of the time. Fewer errors are made over time. Scientist Brenda Milner learned that Henry could do this task, too. He got better and better at tracing the star over time. What was interesting, though, is that Henry couldn’t remember practicing the task. So, even though he could get better at the task from day to day, he could not remember that he had done the experiment the day before. This is an example of how Henry had problems with declarative memory (e.g., trouble remembering the event of doing the task) but no problems with non-declarative memory (e.g., he was able to get better at the skill over time). A person without memory problems could both remember practicing the task and get better over time.

- Figure 4 - Multiple memory systems.

- This picture shows the difference between declarative memory and non-declarative memory. Declarative memory is memory for facts and events. Non-declarative memory is memory for skills and habits. While all of the examples on the left are examples of declarative memory, a person with amnesia probably would not have difficulty with all of them. Can you use what you learned in Figure 2 to guess which examples a person with amnesia would have trouble with? Out of these examples, a person with amnesia would probably only have trouble remembering what they ate for breakfast this morning. They could probably remember a birthday party from when they were a kid. They could probably also remember that George Washington was the first president of the US, if they learned that fact before their injury. But, they would not be able to learn new facts after their injury. Can you think of a new fact that a person with amnesia would have a hard time learning?

Memory Research Today

Today, scientists studying memory still work with patients with amnesia to learn how the human memory system works [7]. Because technology keeps advancing, scientists have many new tools to help them learn about memory and learning [8]. These tools include fMRI, which stands for functional magnetic resonance imaging. fMRI lets scientists see which parts of the brain are doing more work during certain tasks. Scientists can use fMRI to see what healthy people’s brains are doing during memory and learning tasks. Using fMRI has taught scientists that different parts of the hippocampus are important for different things and that other parts of the brain besides the hippocampus are also important for memory. Scientists also study memory and learning in other animals. Mammals like rats and monkeys also have hippocampi and can have memory problems if their hippocampi are damaged.

Scientists study memory in humans and animals to understand how the brain works. They also study memory to learn how to help people who have memory problems. Unfortunately, there is no cure for amnesia. One way scientists have tried to help patients like Mr. Molaison is to use the kinds of memory that they are good at (non-declarative memory) to help them learn things that they usually cannot (new facts, or declarative memory). These techniques do help patients with amnesia to learn new facts, but they do not learn these new facts as quickly or as well as someone with a healthy brain. Scientists are continuing to try to learn about memory, to understand how we learn and remember new things, and to help people with conditions that cause memory difficulties.

Conclusion

Next time you watch a movie or a TV show that shows someone with a memory problem, pay attention to how the movie talks about amnesia. Now you know that amnesia usually does not affect all of a person’s memories, just their ability to form new memories. And you know that while people with amnesia have a hard time learning new facts, they are able to learn new skills. Finally, you have learned that people with amnesia can have severe memory problems, but they usually have normal intelligence and other thinking skills. Most importantly, you have learned that people with amnesia are people just like you and me and have helped scientists learn lots about how the brain works when we learn and remember.

Glossary

Amnesia: ↑ Memory loss or difficulty learning new information.

Hippocampus: ↑ A brain structure important for learning and memory.

Seizure: ↑ Abnormal activity in the brain.

Anterograde Amnesia: ↑ Difficulty learning new information after an injury.

Retrograde Amnesia: ↑ Difficulty remembering things that happened before an injury.

Declarative Memory: ↑ Memory for facts and events.

Non-Declarative Memory: ↑ Memory for skills and habits.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rob Vanderveen for illustrating Figures 2–4 and Eleanor Duff for her comments on an earlier draft. Support provided by NIDCD grant R01 DC011755.

References

[1] ↑ Scoville, W. B., and Milner, B. 1957. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 20:11–21. doi:10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11

[2] ↑ Corkin, S. 2002. What’s new with the amnesic patient H.M.? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3:153–160. doi:10.1038/nrn726

[3] ↑ Ribot, T. 1881. Les Maladies de la Memoire. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

[4] ↑ Corkin, S. 2013. Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of the Amnesic Patient, HM. New York: Basic Books.

[5] ↑ Milner, B. 1962. “Physiologie de l’hippocampe,” in Physiologie de l’’hippocampe, ed P. Passouant, 257–272. Paris: Centra National de la Recherche Scientifique.

[6] ↑ Cohen, N. J., and Squire, L. R. 1980. Preserved learning and retention of a pattern-analyzing skill in amnesia: dissociation of knowing how and knowing that. Science 210:207–210. doi:10.1126/science.7414331

[7] ↑ Rosenbaum, R. S., Gilboa, A., and Moscovitch, M. 2014. Case studies continue to illuminate the cognitive neuroscience of memory. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1316(1):105–33. doi:10.1111/nyas.12467

[8] ↑ Addis, D. R., Barense, M., and Duarte, A. 2015. The Wiley Handbook on the Cognitive Neuroscience of Memory. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.