Abstract

Photographs are not just keepsakes. Images from outer space help us keep track of planet Earth and its resources. Satellites are equipped with special sensors (like eyes) that can see “colors” of light that human eyes cannot see. These satellites orbit really high above us, and travel around Earth frequently. This birds-eye view and speedy revisit time means that they can help inform us about natural disasters, climate change, and the weather. This article gives an overview of how satellites observe the Earth, and some of the important applications of this technique to the conservation of Earth’s invaluable natural resources.

Introduction

The number of humans on Earth is constantly growing. A larger population means that more people need access to natural resources, such as water, land, and minerals. However, these resources are finite, meaning there is only a certain amount of them [1]. Because more people need access to the same number of resources, it has become increasingly important to quickly and accurately map and monitor these resources. Governments and communities monitor resources at global, national, and local levels. We need to know which natural resources are available, how much there are of them, and whether they are healthy or have changed recently. When countries have this information, they can limit their use of resources that are in short supply, so the resources are not overused (see this Frontiers for Young Minds article). Think about forests. Many years ago, humans chopped down trees for fuel, timber for furniture and houses, and to build railways. In the 1700’s, 1800’s, and much of the 1990’s, people did not stop to think about how much forest (especially tropical forests with trees that take hundreds of years to grow) was left to protect the soil against erosion or serve as habitat for birds and other wildlife. Our thinking has changed—we now realize that forests are the lungs of the Earth, and governments and many organizations work to protect forests, limit tree clearing, and replant trees in some areas. To do this, people must first know where trees have been cleared over the years, how much clearing has occured, and where valuable trees still exist and need protection. This is called natural resource management, and pictures taken from above Earth at various timepoints can provide information about where, when, and how many trees have been cleared.

If we want to know how many resources we can use and how fast we can develop an area, we need frequent, consistent, and accurate information captured over large areas of the Earth. Once we have this information we can better understand how lifeforms are interacting with their environments, and then we can reliably monitor and predict how healthy the lands, coasts, and oceans are and what objects or substances are present in those areas (for more information, see this Frontiers for Young Minds article). Fortunately, the technology available to provide this information, called Earth observation, has become more sophisticated over time [2].

What Is Earth Observation?

The first successful unmanned aerial photo of the Earth was taken using a kite, back in 1887. Later, in 1907, a German pharmacist named Dr. Neubronner came up with the idea of mounting a camera to a dove. Over time, Earth observation technology has become more advanced. Humans have learned to launch satellites equipped with cameras. These satellites orbit Earth and take regular pictures of the planet. Approximately 2,200 satellites orbit the Earth, and 446 of those perform Earth observation. Data from these satellites has helped scientists to map many natural phenomena, like drought, floods, and the melting of glaciers. Scientists use this information to better understand the state of the Earth’s natural resources. Satellites can also help scientists spot areas where human activities are damaging the environment, through activities like deforestation, illegal mining, or overgrazing of farmlands.

Satellites Detect Colors We Cannot See

A satellite image is similar to a photograph—kind of like a picture taken with a smartphone and posted on Instagram. Satellite images are created by looking at both light that human eyes can see and light that they cannot see. Our eyes can only see light of certain wavelengths—those that correspond to the colors red, green, and blue—while satellites can see light of many wavelengths. Imagine that your ears could only listen to FM radio, while satellites could listen to both FM and AM radio. Satellites have sensors—kind of like eyes—that can detect certain wavelengths of light that we cannot see. Scientists transform the light information obtained by satellites into images that give them information about the Earth.

Some satellite images, like the ones used as a layer in Google Maps, use the blue, green, and red colors that our eyes can see. Other satellites can take pictures using infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye. Even though we cannot see it, we use infrared light in our everyday lives. For example, the little glass eye at the top of a TV remote uses infrared light to communicate with the television.

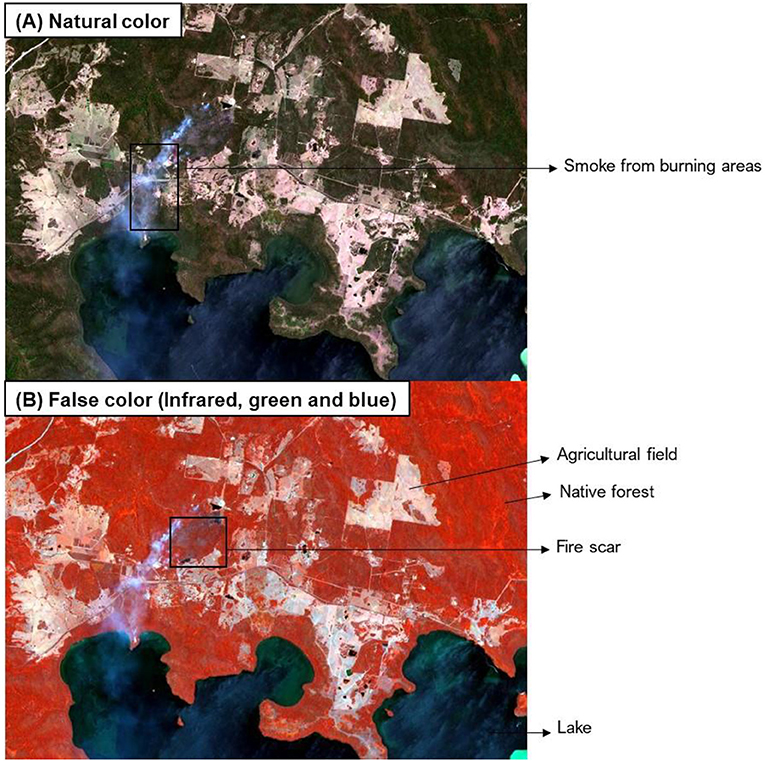

On Instagram, when you look at a photo on which a filter was used to brighten or alter the colors, you might think that it is very artful, or it might look fake. If you see a satellite image with a bright red forest (Figure 1), you might think the same thing—that it must be a fake image. But a red forest is just as real as a dark green one! The difference is that these satellite images are made from wavelengths of light that we cannot see, such infrared, so they do not look real to us. We call these false-color images, and to know what they mean, it is necessary to understand what a satellite image is.

- Figure 1 - A satellite image taken during the Australian bushfires of December 2019.

- (A) This image combines information from the red, green, and blue wavelengths, so you can see the landscape in its natural colors (note the smoke from the bush fire). (B) The burn scar pops out in black in the infrared view, while forests and pastures appears in reddish colors.

What Does a Satellite Measure to Produce an Image?

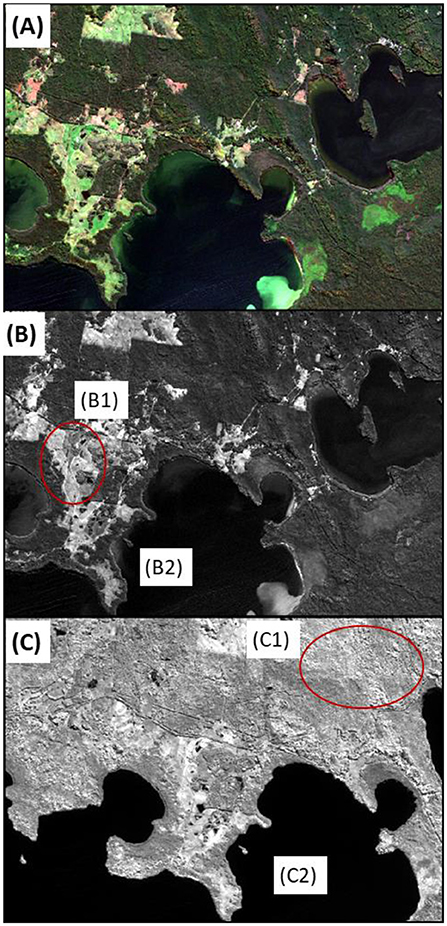

Each of a satellite’s sensors are tuned to detect a narrow range of wavelengths—just blue light, for instance. Images made from only one wavelength appear in shades of gray (Figure 2). Objects on Earth that produce a lot of that particular wavelength of light appear as bright spots, while objects that reflect or produce little (or none) of that wavelength appear as dark grays or even black. The information captured by all the satellite’s sensors is stored in images called multi-spectral remote sensing data (Figure 2).

- Figure 2 - (A) A satellite multi-spectral image that combines blue, green, and red light.

- [(B), B1] A part of the landscape that reflects a lot of light shows as bright spots in this image taken by the blue eye of the satellite. [(B), B2] The water of the lake reflects almost no light and appears black. [(C), C1] In this image taken by the infrared eye of the satellite all vegetation reflects a lot of light (very bright spots). [(C), C2] The water of the lake reflects no light and appears black. The meaning of the red circle is to show the bright spots.

For example, to the human eye, healthy plants appear green because plant pigments reflect more green light than other wavelengths, and they absorb more red and blue light [3]. But special types of sensors in satellites are designed to pick up infrared light, and healthy vegetation reflects a large amount of infrared light from the sun [3]. Therefore, healthy plants appear red via remote sensing.

Distance From Earth Matters

Satellites can orbit at various distances from Earth—from about 36,000 km away to only 800 km away. Satellites that orbit at 36,000 km above Earth are called geostationary, and they can help with weather forecasts. Geostationary satellites look at just one of Earth’s hemispheres, and they can take pictures approximately every 10 min. They help scientists map how clouds and hurricanes move, and they can even collect information on how volcanoes erupt! But because they are so high, they give low-quality pictures of Earth, like old movies. The smallest objects they can see are 500–1,000 m in size.

Satellites that orbit closer to Earth can take pictures using the both visible (to humans) and invisible wavelengths of light. These satellites can see objects as small as 0.5–30 m in size—ranging from the size of a car to an average backyard! Because they orbit around Earth, they take pictures of the same location every 5–16 days, or even less often if several satellites are working together as a team (for an example, see Planet Labs).

Protecting Earth’s Resources

Satellites are like Earth’s bodyguards. Observing Earth from satellites has many advantages. They can cover large regions such as the entire American continent, even the whole earth. Monitoring the Earth’s resources can be systematic and continuous using satellite images. For instance, Global Forest Watch uses images from satellites to monitor the amount of forest clearance in places like the Amazonia or the Congo.

Satellite observations give consistent data that can be shared by many users for different purposes. These data provide information needed to identify problems, make decisions and take actions to protect the natural environment, to plan for help after disasters, and detect and predict changes to safeguard our planet’s precious resources. Did glaciers melt last year? How much damage did the wildfires cause? How many hectares of forest were cleared over the last 12 months? Thanks to the hundreds of Earth observing satellites that orbit our planet we can answer questions like these, and learn about the status of land, water, and the atmosphere. Satellite Earth observation keep a watching eye over our invaluable natural resources and give us information to manage better our world now and in the future.

Glossary

Natural Resource Management: ↑ Integrated management of the natural resources that make up Earth’s natural landscapes, such as land, water, soil, plants, and animals.

Earth Observation: ↑ Looking down at the Earth from aircraft or satellites using various sensors that create images used to study what is happening on or near Earth’s surface.

Drought: ↑ A long period of time of abnormally low rainfall, leading to a shortage of water.

Wavelength: ↑ The distance between the tops of the waves, like light waves. The wavelength of light determines the colors we see.

Infrared: ↑ Infrared light is part of the electromagnetic radiation spectrum. Infrared waves are longer than visible light waves, but not as long as radio waves.

Multi-Spectral Remote Sensing Data: ↑ Acquisition of visible, near infrared, and short-wave infrared images in several broad wavelength bands.

Infrared Light: ↑ The part of the invisible wavelenghts that is next to the red end of the visible light.

Remote Sensing: ↑ The process of detecting and monitoring the physical characteristics of an area by measuring its reflected and emitted light at a distance, typically from satellites or aircraft.

Geostationary: ↑ A satellite that appears nearly stationary in the sky as seen by a ground-based observer.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No. 870518.

References

[1] ↑ Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F. S., Lambin, E. F., et al. 2009. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461:472–5. doi: 10.1038/461472a

[2] ↑ CRCSI. 2016. Earth Observation: Data, Processing and Applications. Volume 1A: Data—Basics and Acquisition. Melbourne, VIC: Australia and New Zealand CRC for Spatial Information.

[3] ↑ Huete, A. 2004. Remote Sensing for Environmental Monitoring. Environmental Monitoring and Characterization. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 183–206.