Abstract

Pain is a common experience in everyday life and part of our earliest experiences as babies and toddlers. Most pain that we experience does not last very long and is “helpful,” as it teaches us how to avoid situations that can cause us harm. However, not all pain is short term or helpful. Pain that is continuous or comes and goes for a minimum of 3 months is called chronic pain. Chronic pain is common in children and teenagers and can affect many areas of young people’s lives, such as sport, school, sleep, mental health, and friendships. Unfortunately, we do not understand this experience of chronic pain in young people, and how it affects their lives, very well at all. It is really important that we develop a better understanding of how we can support young people with chronic pain and their families to live full lives.

What is Pain and How Do We Describe It?

Asking a question like, “What is pain?” might seem silly. Surely everyone knows what pain is, do not they? You accidentally brush your hand on a hot stove or bang your elbow on a table and suddenly it hurts. Pain is a common part of everyday life and it helps us to learn to avoid situations that might cause us harm. Once you know that touching a hot stove is painful, you try to avoid doing it again.

Pain is also a big part of our earliest life experiences. Toddlers fall down and bump into things as they learn to walk and babies cry at the sudden pain of a routine injection. In a recent study, researchers observed children aged 1–2 years in a play centre and reported at least one painful event (such as a fall or a bump) per hour per child [1]. Luckily, these types of painful experiences usually last only for a short time and then go away. This type of pain is called acute pain.

Pain is not always short lived, however. You may well be able to think about times where pain has lasted for a really long time, even if it is not present all the time. Examples can include experiencing regular headaches or breaking an arm over a year ago, but still experiencing pain in this arm and not being able to use the arm properly. This is an example of pain that is not helpful as it is not providing any useful function, such as preventing use of an injured arm. Pain that is continuous, or comes and goes for at least 3 months, is called chronic pain. Unfortunately, we do not understand the experience of chronic pain very well.

To try and better understand the experience of chronic pain, various measures have been developed to measure the severity of the pain experience. There are numerous ways in which pain can be measured, from observing pain behaviours, such as grimaces in babies, to asking young people to rate their pain on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). Measures like these are called numerical rating scales and focus on assessing the “severity” of pain.

How Common is Chronic Pain in Young People?

We know that chronic pain is commonly experienced by children and teenagers (we will use the term “young people” to refer to the combined group of children and teenagers throughout the article). A recent study conducted across 42 different countries found that 44.2% of young people reported experiencing weekly pain over the past 6 months, with rates differing between countries [2]. Remember that this number says nothing about the impact of this pain on the lives of these young people, with many young people likely living a full life. An older study of young people with chronic pain highlighted that about 5.1% of young people with chronic pain had pain so severe that it impacted their daily lives, stopping them from doing things that they wanted to do [3].

The research data tell us that chronic pain is more common in girls and that the experience of chronic pain increases as children become teens. We do not know why pain increases during puberty or why it is more common in girls, although higher levels of chronic pain have also been found in women compared with men.

Chronic pain can be part of an ongoing health condition in young people, such as arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, or chronic fatigue syndrome, or it can occur for no obvious reason at all. Research is beginning to look at why some young people develop chronic pain. For example, one current study is looking at why some young people still experience pain even once a fractured bone has healed. You can read more about this study here.

How Can Living With Chronic Pain Affect Young People’s Lives?

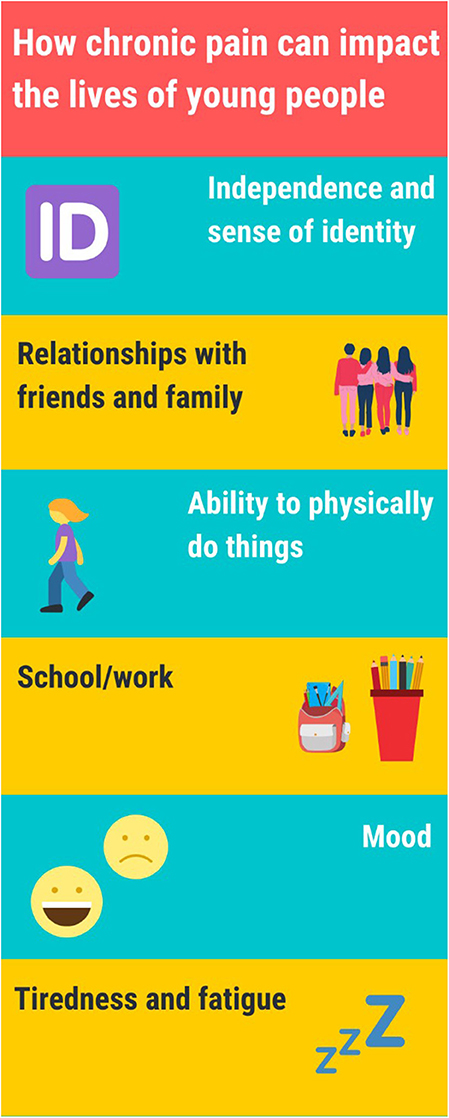

There are lots of different ways that living with chronic pain can affect young people’s lives (Figure 1). We know that it can make it difficult for young people to sleep, take part in sports, concentrate, attend school and go out with friends or family. With this in mind, it is not surprising that one of the biggest challenges that young people who live with chronic pain face is poor mental health. In fact, young people report high levels of anxiety and depression, with some mental health problems remaining as the young person becomes an adult [4].

- Figure 1 - Some of the ways that chronic pain can impact various aspects of young people’s lives.

Chronic pain also often disrupts young people’s school life. We know that living with chronic pain can make attending school difficult, with young people missing many school days. One US based study found that young people with chronic pain that is not related to a medical condition missed almost nine school days over 3 months, resulting in greater absences than young people with arthritis and pain free young people [5]. In some extreme cases, studies have shown that young people who are very disabled by their ongoing pain may have to repeat a year. Even if these young people can attend school, experiencing constant pain can make it difficult to concentrate and take part in activities. Missing out on school activities can disrupt learning and also make it difficult to make new friends or keep up with existing friends.

Living with chronic pain can also affect young people’s sense of who they are and what makes them unique. We call this process forming personal identity. Forming personal identity is tricky for any young person, but can be particularly challenging for young people who need to find a sense of who they are despite living with chronic pain [6]. For some young people, their pain becomes part of their sense of who they are, so they see themselves as teenagers who live with chronic pain. Other young people are keen to think about their pain as separate from their sense of who they are. So, they see themselves as people who love dancing and chatting with friends but who just happen to live with chronic pain.

The impact of chronic pain can extend beyond the young person and affect their parents and caregivers. In particular, we know that parents of young people who live with ongoing pain often report feeling anxious and depressed. Studies have also shown that parents of young people who are extremely disabled by their pain report challenges with managing a full social and work life. This impact on parents’ lives is often because their child with pain is heavily dependent on them, much more so than young people of a similar age who do not experience pain [7].

How Do Others Make Sense of Pain That is Hard to See?

One of the biggest problems faced by young people with chronic pain is that pain is often invisible to others. If you break your leg, you might have your leg in a cast. This cast makes it easy for people to see your pain, and it is a clear sign to be careful around your leg. It also lets other people know to be patient with you, since you would not be up and running around for the next few weeks. But what happens when pain is ongoing and there is no obvious cause or no visible sign, maybe “just” a painful back that is better some days than others? So, one day you can make it into school, but the next day you cannot, because it is too painful to get out of bed. Friends, family, and teachers might find it really tricky to understand how you can experience ongoing pain when they cannot see what is causing the pain or how pain levels can change very quickly from day to day. Friends might find it difficult to understand why you sometimes need to cancel plans at the last minute when you feel poorly. If this happens frequently, your friends could think that you do not want to hang out with them anymore, and no longer invite you to meet up. Issues like this make it harder for young people with chronic pain to maintain friendships. Scientists do not know much about the long-term effects that tricky friendships in the teen years can have on young people with chronic pain as they get older.

What Treatments Are Available for Young People Who Experience Chronic Pain?

You might think that drugs are the obvious choice for managing chronic pain in young people, but in actual fact, we do not know a lot about whether drugs, and which drugs, help reduce chronic pain in young people. That is not to say that drugs do not work or that doctors do not use them in these cases, but simply that not enough good quality studies have looked at this issue. So, what do we know?

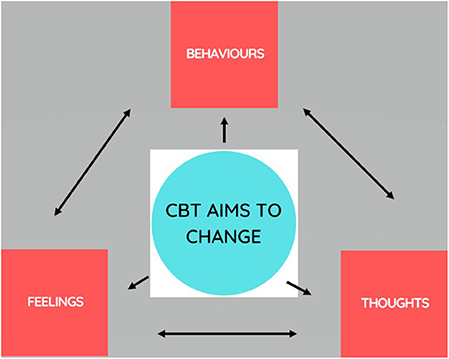

We do know that psychological techniques, such as setting achievable goals and relaxation, can be useful for helping young people with chronic pain to get back to doing the things they want to do, like going out with friends, going to school, or playing sports. These psychological treatments might include things like cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which aims to change how young people think and feel about their pain and how they (and others, like parents and teachers) respond when they experience pain. Figure 2 shows how CBT treatment addresses thoughts, feelings, and behaviours about a particular phenomenon—in this case, chronic pain.

- Figure 2 - Cognitive behavioural therapy can be used to treat chronic pain.

- In CBT, treatment addresses thoughts, feelings, and behaviours about a particular phenomenon—in this case, chronic pain.

For example, lots of young people are understandably worried about the possible damage that moving a painful area might cause to their body. Not moving painful areas over time can lead to loss of muscle strength and fitness. To help young people engage in gentle movement of painful areas, CBT challenges their thoughts and feelings about what will happen if they try move the painful area. CBT does not usually focus on reducing the pain itself, but instead focuses on reducing the disruptive impact pain has on the young person’s life. There is good evidence available that CBT helps young people to get back to doing the activities that are important to them [8].

A newer therapy for treating chronic pain in young people is called acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Although it has some similarities with CBT, ACT focuses on helping young people to accept their pain and to stop struggling over changing difficult thoughts and behaviours related to pain. ACT encourages young people to focus on the present, through activities, such as mindfulness exercises and allowing thoughts to occur in a way that is not overwhelming. ACT hopes to achieve the same goal as CBT: to help young people begin to take part in activities that they value, like going out with friends. However, not many studies have used ACT to treat chronic pain in young people, so there is not yet much evidence to tell us whether ACT is effective in supporting young people to manage their pain and its effects.

Neither CBT nor ACT focus on reducing the pain itself. Instead, they focus on reducing the disruptive impact pain has on the young person’s life, by supporting young people (and their parents) to address things that the young people can change and that are important to them. These treatments often involve working to improve sleep, mood, and exercise or movement. Young people and their parents can take part in CBT and ACT either individually or with a group, and either face-to-face or online. Young people tend to enjoy a group approach, as this means they get to meet other young people who truly understand what it is like to live with chronic pain. Interestingly, some CBT and ACT treatment programmes for chronic pain in young people are also beginning to include parents as well as young people.

Conclusion

We hope that we have shown you that chronic pain is a common experience for children and teenagers and that, for a smaller group of young people, it has a huge impact on many areas of their lives and the lives of their parents and families. The experience of chronic pain is complicated, because everyone experiences pain differently. Additionally, the fact that chronic pain itself is often invisible makes it difficult for others to understand, but also difficult for young people themselves to make sense of the pain. While some help is available for young who experience chronic pain, more research is needed to understand which treatments work best for which young people and their families. To address the issue of the invisibility of pain, it is very important to increase public awareness of how chronic pain can affect young people and what can be done to support them.

Glossary

Acute Pain: ↑ Pain that lasts <3 months.

Chronic Pain: ↑ Pain that lasts for 3 months or longer.

Arthritis: ↑ A health condition that causes swelling, stiffness, and pain in a person’s joints.

Personal Identity: ↑ A sense of who you are as a person and what makes you unique.

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT): ↑ A psychological therapy that involves changing the way that people think and behave about pain.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): ↑ A psychological therapy that focuses on accepting pain and giving up the struggle to change thoughts and feelings about pain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Noel, M., Chambers, C. T., Parker, J. A., Aubrey, K., Tutelman, P. R., Morrongiello, B., et al. 2018. Boo-boos as the building blocks of pain expression: an observational examination of parental responses to everyday pain in toddlers. Can. J. Pain 2:74–86. doi: 10.1080/24740527.2018.1442677

[2] ↑ Gobina, I., Villberg, J., Välimaa, R., Tynjälä, J., Whitehead, R., Cosma, A., et al. 2019. Prevalence of self-reported chronic pain among adolescents: evidence from 42 countries and regions. Eur. J. Pain 23:316–26. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1306

[3] ↑ Huguet, A., and Miró, J. 2008. The severity of chronic pediatric pain: an epidemiological study. J. Pain 9:226–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.10.015

[4] ↑ Leino-Arjas, P., Rajaleid, K., Mekuria, G., Nummi, T., Virtanen, P., and Hammarström, A. 2018. Trajectories of musculoskeletal pain from adolescence to middle age: the role of early depressive symptoms, a 27-year follow-up of the Northern Swedish Cohort. Pain 159:67–74. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001065

[5] ↑ Agoston, A., Gray, L., and Logan, D. 2016. Pain in school: patterns of pain-related school impairment among adolescents with primary pain conditions, juvenile idiopathic arthritis pain, and pain-free peers. Children 3:39. doi: 10.3390/children3040039

[6] ↑ Jordan, A., Noel, M., Caes, L., Connell, H., and Gauntlett-Gilbert, J. 2018. A developmental arrest? Interruption and identity in adolescent chronic pain. Pain Rep. 3:e678. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000678

[7] ↑ Jordan, A. L., Eccleston, C., and Osborn, M. 2007. Being a parent of the adolescent with complex chronic pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eur. J. Pain. 11:49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.012

[8] ↑ Fisher, E., Law, E., Dudeney, J., Palermo, T. M., Stewart, G., and Eccleston, C. 2018. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9:CD003968. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003968.pub5