Abstract

Pain is a natural signal that helps us protect our bodies and is essential for survival. But sometimes pain can be harmful—like in the case of inflammatory pain, which causes long-term discomfort and even damage. Scientists and doctors want to understand exactly how pain signals travel in the body, so they can find better treatments for people who suffer from long-lasting pain. In our laboratory, we study the tiny nerve endings that act as the body’s pain sensors (e.g., in the skin or intestines). We look at how changes in these nerve endings affect the way pain messages move from different body parts, such as a fingertip, to the brain and spinal cord. By discovering what changes happen in these nerve endings, we hope to understand the causes of inflammatory pain and to develop new medical treatments that can reduce pain without harmful side effects.

Pain: An Important Role And A Medical Challenge

Pain is something that every person feels. Even though it is unpleasant, pain is very important because it protects us. It warns us when our bodies are in danger and helps us avoid further harm. Without pain we might not notice injuries, and our bodies would be less safe. Think about what happens if you touch a hot stove. Your hand pulls back very quickly, almost before you realize it. This happens because special nerves under the skin, called nociceptors, send a fast signal to the brain that says, “This is dangerous—move away!”. Pain acts like an alarm system that helps keep us safe.

Pain becomes more problematic when it lasts for a long time and has harder-to-understand sources. One reason this can happen is inflammation. Inflammation is a normal process that helps the body fight germs or heal an injury. For example, when you have a stomach virus, you might feel stomach pain and develop a fever. This is the body’s way of protecting itself and encouraging rest until it gets better. In other words, the pain signals to us that something is wrong, so we try to rest and not eat foods that make the digestive system work hard. Usually, after a few days, we feel better because the body has managed to fight off the virus.

Sometimes though, inflammation continues for a long time without a clear cause. An example is Crohn’s Disease, where inflammation is not caused by anything harmful coming from outside the body. Instead, the immune system makes a mistake and causes long-lasting inflammation in the digestive tract. In these sorts of diseases, pain can remain even without a clear cause. This means scientists also need to find treatments that address the pain itself.

To develop better pain treatments, scientists first need to understand how pain signals travel through the body. The pain pathway has two main parts: the peripheral nervous system and the central nervous system. The peripheral nervous system is made up of nerves that gather information from the skin, stomach, eyes, arms, and legs and send it to the central nervous system. The central nervous system, composed of the spinal cord and brain, receives this information, processes it, and sends commands back to the body.

Along this pathway, many things can change the way pain is felt. In the brain and spinal cord, information might be processed differently. Even in the peripheral nervous system, the nerves themselves can become more sensitive, change their structure, or send signals faster or more often. All of these changes affect how pain signals are carried to the brain.

In this article, we will focus on the very end of the nerve, called the nerve terminal. Changes at the nerve terminal are important in many pain disorders. We will also describe new research methods that allow scientists to study these tiny structures and see how they behave.

How Does the Body Send Pain Information to the Brain?

Nerves are designed to carry messages through the body. These messages travel using tiny electrical signals, created when small particles, called ions (like sodium and potassium), move in and out of the nerve cell. There are many types of nerves, but the ones that send pain signals are called nociceptors. Each neuron has a main part, called the soma, which contains everything the cell needs to stay alive. From the soma, two long branches extend, a bit like two arms. One branch picks up information from the body’s organs, like the skin or muscles. The other branch sends the information toward the spinal cord and then to the brain. These branches are called axons, and you can imagine them like roads that connect the body to the brain. Along the axon, ions quickly move in and out, helping the signal travel very fast. At the very end of the axon are many small branches, called nerve terminals. This is where the signal starts before traveling along the axon to the soma and finally to the brain.

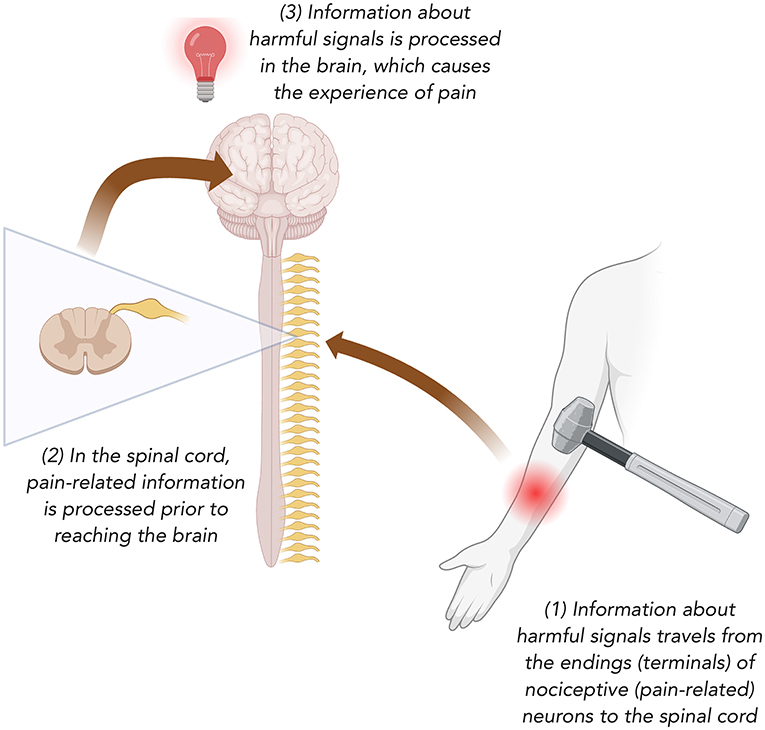

Nociceptors have tiny detectors on their terminals that can recognize many different things that cause pain—such as very high temperatures or even the chemical in chili peppers that makes food spicy. When one of these detectors is triggered, the nociceptor sends a signal along its axon to the brain. The brain then interprets this signal, and we experience it as pain (Figure 1) [1].

- Figure 1 - How pain travels from the hand to the brain.

- Imagine you hit your forearm with a hammer. (1) The pain signal is picked up by special injury-sensing nerves called nociceptors. (2) The signal then travels to the spinal cord, where it is partly processed. (3) From there, it continues to the brain. The brain receives the message and recognizes it as pain.

How Can We Study Nerve Endings in A Living Organism?

For many years, it was very hard for scientists to study nerve terminals, because they are usually hidden deep inside organs [2]. To see them, researchers often had to remove nerves from the body, which made it difficult to understand how they really work in a living animal. In our lab, we wanted to look at nerve terminals of nociceptors while they were still inside the body. To do this, we needed to find a place where the terminals are easy to see without harming the animal. We discovered that the cornea (the clear outer layer of the eye) is perfect for this. Because the cornea is transparent, we can see the terminals directly through it.

Here is how the method works: first, we inject a special substance into the animal (in this case, a mouse), which glows when the nerve terminal is active. Using a microscope, we can watch the glowing terminals in real time. This allows us to study how the terminals behave under normal conditions and also when the animal is experiencing pain or inflammation [3].

What Changes Happen In Nerve Terminals During Pain?

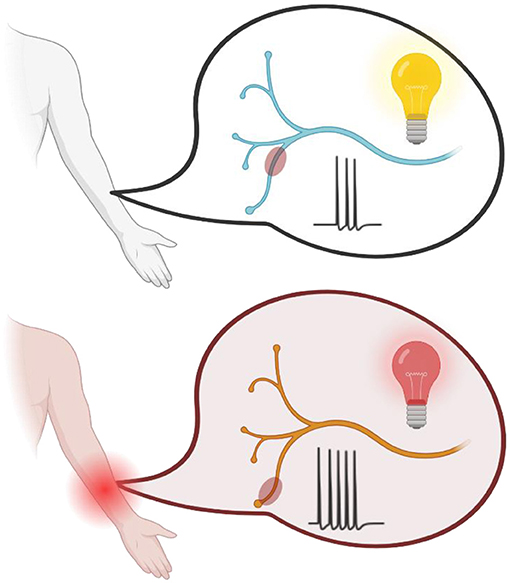

You might have noticed that, when you are sick or injured, things that are usually not painful can suddenly hurt a lot. For example, swallowing water feels normal when you are healthy, but it can be very painful if you have a sore throat. Why does this happen? To try to answer this question, we used our special method to watch nerve terminals of nociceptors in the cornea. We compared how they behave when the body is healthy and when there is inflammation. Normally, a pain signal begins partway along the terminal and then travels along the axon to the brain. But during inflammation, we discovered that the starting point of this signal moves closer to the very end of the nerve (Figure 2) [3, 4]. This change means the nerve sends out more frequent and stronger signals. It is a bit like rolling a rock down a mountain: the higher up you let go of the rock, the more speed it builds, and the more likely it is to reach the bottom. In the same way, when the starting point of the signal moves closer to the terminal, the signal has a greater chance of reaching the brain. The brain then interprets this extra activity as stronger pain. This can help explain why simple actions, like swallowing, can feel much more painful when the throat is inflamed.

- Figure 2 - How inflammation changes the pain signal.

- (upper panel) When there is no inflammation, the pain signals start farther away from the nerve terminal, and only a few signals (three here) are sent to the brain. (lower panel) During inflammation, the starting point of the signal moves closer to the nerve terminal, and more signals (five here) are sent. The brain interprets this extra activity as stronger pain.

Can We Block Pain At The Nerve Terminal?

Today, medicines for pain are limited, especially for people with stomach and intestinal diseases. Many patients with conditions like inflammatory bowel disease suffer from strong abdominal pain, but often there are no good treatments. In our lab, we wanted to see if we could use what we had learned about nerve terminals to stop pain right where it begins.

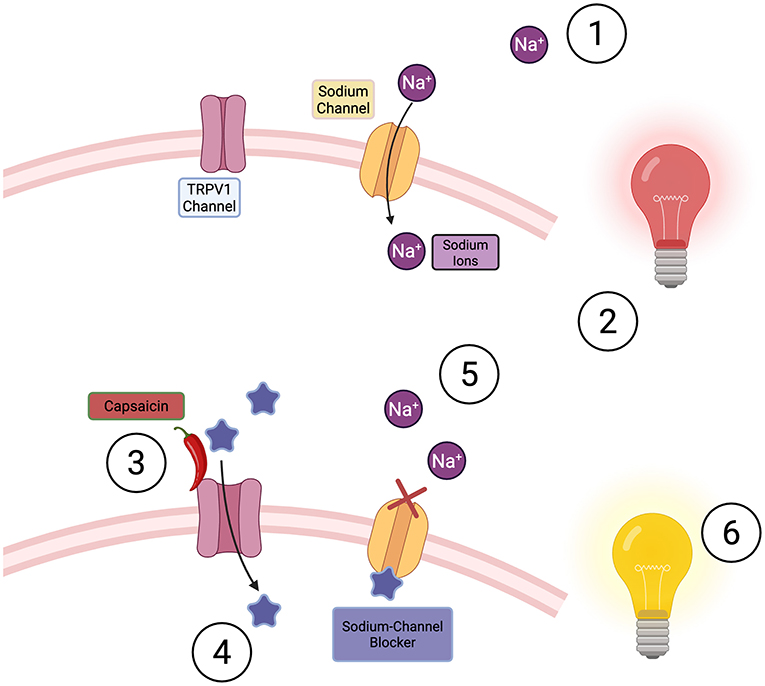

Remember the detectors on nociceptor terminals that sense harmful things, like heat or the spicy chemical in chili peppers? One of these detectors is called TRPV1. When TRPV1 opens—such as when activated by chili pepper—it creates a “gateway” into the nerve. We demonstrated that, while this gateway is open, scientists can deliver a special substance into the nerve that blocks sodium channels [5]. Sodium is the ion that nerves need to create and send electrical signals. If sodium channels are blocked, the nerve cannot send the pain message to the brain. Using this method, we could block pain signals in general [5] (Figure 3) and specifically in the intestines of rats [6]. This result showed that, in the future, it may be possible to treat abdominal pain by targeting pain at the very first step, the nerve terminal.

- Figure 3 - During inflammation in the bowel, sodium ions flow into the cell (1).

- This causes a chain of events that sends a painful signal to our brain (2). When we administer capsaicin, we activate TRPV1 channels (3). This allows sodium-channel blockers to enter the cell (4), sodium can no longer enter the cell (5), so no information can be further transmitted (6). This means no painful signal is sent to the brain.

Following Pain’s Path to Find Better Treatments

In our research, we focus on how pain signals travel from the body to the brain and how changes along this pathway can lead to long-lasting or very strong pain. By developing new methods to study the tiny nerve terminals, we can see how pain signals start and how inflammation makes them stronger. This knowledge does not just help us understand pain better—it also shows us new ways to treat it. By targeting pain at the nerve ending itself, we may be able to create treatments that reduce pain more effectively and with fewer side effects. Our goal is to take what we learn in the lab and turn it into real solutions that can help people who suffer from chronic pain.

Glossary

Nociceptor: ↑ A special type of nerve cell whose job is to detect harmful things and send pain-related signals to the brain.

Inflammation: ↑ The body’s reaction when injured or fighting germs, which includes the production of substances that protect tissues. Sometimes inflammation can go on too long or happen by mistake.

Nerve Terminal: ↑ The very end of the axon, often inside an organ. This is where pain signals begin before they travel to the brain.

Ions: ↑ An ion is an atom or molecule that carries an electric charge. In the body, ions have positive or negative charges and are important for creating electrical signals in nerve cells.

Soma: ↑ The “main body” of a nerve cell. It contains the parts that keep the cell alive and working.

Axon: ↑ A long branch of a nerve cell that carries information with the help of tiny particles called ions, like a road connecting different parts of the nervous system.

TRPV1: ↑ A “gate” on pain-sensing nerve cells that reacts to high heat or spicy substances like chili peppers.

Sodium Channels: ↑ Sodium channels are tiny protein tunnels in the membrane of a nerve cell that let sodium ions enter the cell. These sodium ions help initiate and propagate electrical signals that allow nerve cells to communicate.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

[1] ↑ Binshtok, A. M. 2011. Mechanisms of nociceptive transduction and transmission: a machinery for pain sensation and tools for selective analgesia. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 97:143–77. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385198-7.00006-0

[2] ↑ Aleixandre-Carrera, F., Engelmayer, N., Ares-Suárez, D., Acosta, M. D. C., Belmonte, C., Gallar, J., et al. 2021. Optical assessment of nociceptive trp channel function at the peripheral nerve terminal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:481. doi: 10.3390/ijms22020481

[3] ↑ Gershon, D., Negev-Goldstein, R. H., Abd Al Razzaq, L., Lev, S., and Binshtok, A. M. 2022. In vivo optical recordings of ion dynamics in mouse corneal primary nociceptive terminals. STAR Protoc. 3:101224. doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2022.101224

[4] ↑ Goldstein, R. H., Barkai, O., Íñigo-Portugués, A., Katz, B., Lev, S., Binshtok, A. M., et al. 2019. Location and plasticity of the sodium spike initiation zone in nociceptive terminals in vivo. Neuron 102:801–12.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.03.005

[5] ↑ Binshtok, A. M., Bean, B. P., and Woolf, C. J. 2007. Inhibition of nociceptors by TRPV1-mediated entry of impermeant sodium channel blockers. Nature 449:607–10. doi: 10.1038/nature06191

[6] ↑ Mazor, Y., Engelmayer, N., Nashashibi, H., Rottenfußer, L., Lev, S., Binshtok, A. M., et al. 2024. Attenuation of colitis-induced visceral hypersensitivity and pain by selective silencing of TRPV1-expressing fibers in rat colon. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 30:1843–51. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izae036