Abstract

More than three-quarters of the Earth is covered by the ocean, home to millions of sea creatures. Tiny plants in the surface ocean use energy from the sun to grow, producing the oxygen we breathe. When these plants die, their remains sink like snowflakes into the deeper ocean, where bacteria and small animals break them down through a process called respiration. If respiration happens near the surface, carbon dioxide is released back into the air, but when respiration occurs deeper, the carbon dioxide stays trapped for a long time, helping to regulate Earth’s climate. Scientists face challenges in measuring respiration in the dark, cold, and high-pressure depths of the ocean. In this article, we explore how researchers worldwide are solving this puzzle and how you can help protect ocean life.

The Sunlit Zone: The Ocean’s Vegetable Garden

Sunlight only reaches the upper few hundred meters of the ocean (Figure 1A), but this sunlit layer, called the euphotic zone, is where most of the food for marine life is produced. Just like plants on land, tiny marine plants called phytoplankton need sunlight to grow. Phytoplankton cells with chlorophyll use sunlight, carbon dioxide (CO2), and nutrients from the water to produce oxygen (O2) and energy-rich, sugar-like compounds through photosynthesis (Figure 1B). Think of the sunlit zone as the ocean’s vegetable garden, where phytoplankton are the vegetables providing food for marine life in the entire ocean, including the deepest, darkest ocean trenches. Tiny animals called zooplankton [1] eat the phytoplankton and then serve as a food source for larger marine creatures such as fish and whales. This transfer of energy from tiny plants to big ocean animals is what keeps the marine food web running [2].

- Figure 1 - (A) Respiration and photosynthesis by bacteria, phytoplankton, zooplankton, fish and other animals in the ocean.

- Organic matter rains down like snow, providing food for bacteria and fungi. Gases such as oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2), which are used and produced by photosynthesis and respiration, can move easily between the air and the water. (B) The process of photosynthesis. (C) The process of respiration.

The Mysterious Dark Zone: The Mesopelagic

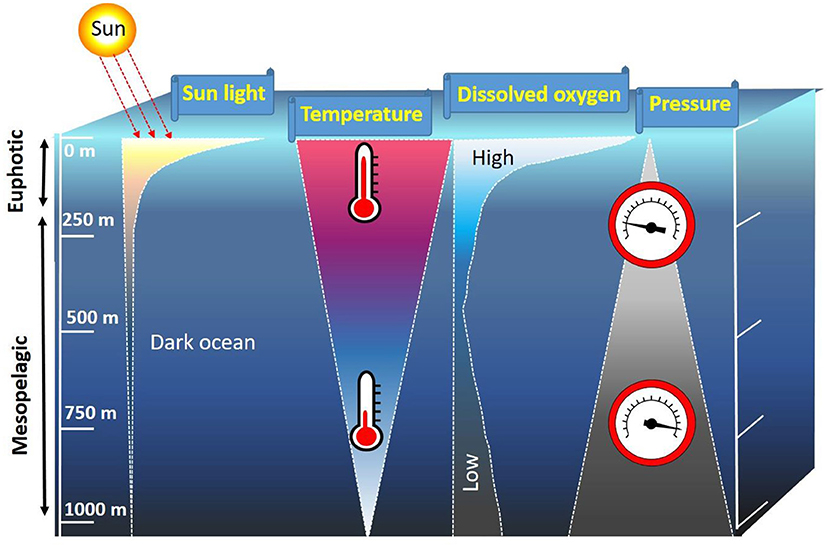

Between the surface sunlit layer and the deepest parts of the ocean, some reaching depths of 11,000 m (deeper than Mount Everest is tall), lies the mesopelagic zone [3], stretching from 200 to 1,000 m deep. No sunlight reaches the mesopelagic zone, making it a dark and mysterious place. Temperatures drop to just 2–4°C, and the pressure is almost 100 times greater than at the surface, due to the weight of the water above (Figure 2). Despite these extreme conditions, the mesopelagic is full of life. Millions of bacteria live here, along with strange-looking animals like worms, giant squid, and octopuses. This zone is also home to nearly all of the world’s marine fish. Even in total darkness, life in the mesopelagic is incredibly active.

- Figure 2 - Decreases in light and temperature, changes in dissolved oxygen and increases in pressure between the euphotic and mesopelagic zones of the ocean.

- Oxygen is highest in the surface waters due to photosynthesis and diffusion from the atmosphere and lowest at mid depths due to high respiration. Cooling of surface waters in polar regions causes cold oxygen rich surface waters to sink and move along the seafloor as if along a conveyor belt throughout the oceans. This means that the deepest waters have oxygen concentrations slightly higher than those in the waters immediately above.

Respiration: How Animals and Bacteria Produce Energy

Creatures in the mesopelagic ocean are constantly respiring, just like humans and animals on land. This means they breathe in O2 and breathe out CO2 to break down food and produce energy. The energy produced during respiration is stored in a special chemical called adenosine triphosphate (ATP; Figure 1C). Think of ATP like a rechargeable battery. This battery powers important activities, such as growth and movement. The process that helps produce ATP is called the electron transport system, which allows energy to flow and keep ocean life going, even in the deep, dark sea.

Marine Snowflakes

When phytoplankton, zooplankton, and fish die or produce waste, such as poop, they create tiny particles of organic matter that sink through the water [4]. These particles clump together to form “marine snow”, which falls from the surface ocean to the mesopelagic zone, just like snowflakes falling from the sky (Figure 1A). As marine snow sinks, it becomes food for bacteria, zooplankton, and deep-sea fish. These deep-sea creatures break down the organic matter and release CO2 when they respire. The speed at which marine snow sinks is important. If it sinks quickly, more of the organic matter reaches the deep ocean, but if it sinks slowly, much of it gets eaten and turned into CO2 before it can sink very deep. In fact, about 90% of the organic food produced in the sunlit ocean is respired by creatures in the surface and mesopelagic ocean, turning the organic matter into CO2 and nutrients. The mesopelagic zone acts like the ocean’s compost bin, where bacteria and fungi recycle dead organic matter into nutrients that fuel ocean life.

In addition to sinking particles, some organic matter dissolves into the water, forming dissolved organic matter (DOM). This is similar to sugar dissolving in a cup of tea—you cannot see it, but it is still there! DOM is an important food source for bacteria and fungi in the ocean. However, some DOM is either too dilute or not tasty enough for microbes to consume, meaning it does not get broken down and turned into CO2. Instead, it builds up and creates a huge carbon storage system in the ocean. In fact, the ocean holds more carbon in DOM than in all of the plants and trees on land combined, and some of this carbon can stay in the ocean for thousands of years.

The combination of respiration, which breaks down most of the organic matter falling from the surface, and the long-term storage of DOM for thousands of years, makes the mesopelagic zone a key player in the ocean’s carbon cycle. This has important implications for climate change, as the ocean helps regulate the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere.

How do Scientists Measure Respiration in the Mesopelagic Ocean?

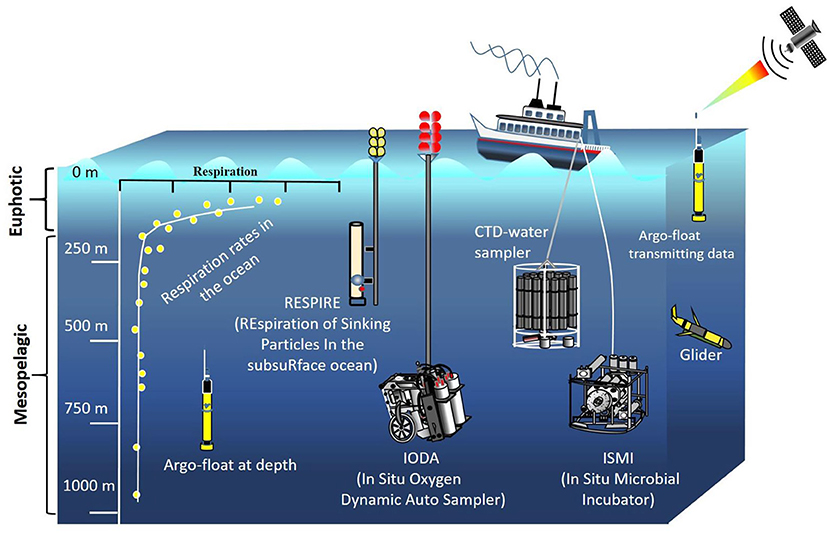

Scientists are using amazing technologies to understand how bacteria and other creatures respire in the mesopelagic ocean and, more importantly, to predict how climate change might affect their respiration in the future. Underwater robots, called Argo floats and gliders, are equipped with special sensors that measure the decrease in oxygen caused by respiration (Figure 3). These robots can explore areas that humans cannot reach and send their data back to scientists via satellites, giving us valuable information about the ocean’s deep, hidden processes.

- Figure 3 - There are various ways to measure respiration in the mesopelagic zone, including from the decrease in dissolved oxygen measured by sensors on the CTD, gliders and Argo floats, from sensors inside the RESPIRE and IODA sampling devices and from the green color of a special dye added to a water sample within an in situ microbial incubator (ISMI).

Scientists have also designed special instruments that can measure respiration in the cold, high-pressure conditions of the mesopelagic ocean. Measurements taken directly in the ocean, rather than from samples brought back to the surface, are called in situ measurements. Tools like the IODA and RESPIRE samplers (Figure 3) are programmed to take in situ measurements of the decrease in oxygen caused by the respiration of plankton or microbes that are within particles of organic matter. Another tool, called the in situ microbial incubator, adds a dye to the deep-water sample, which attaches to bacteria and glows green when they respire. The brighter the green color, the greater the respiration, making it easier for scientists to track the process in situ.

Oxygen sensors deployed from research ships, along with sensors that measure the saltiness, temperature, and pressure of the water (using an instrument called a CTD), can also help scientists study respiration in the ocean. To do this, scientists measure certain gases which dissolved in the water, along with oxygen, when the water was last in contact with air. These gases act like a time clock, helping scientists figure out how long respiration has been happening. This “age” can range from decades to hundreds of years, and scientists use it to calculate how much respiration happens each year.

Another clever way of measuring respiration is by detecting the activity of the enzymes in the electron transport system, which all cells use to produce energy during respiration. Scientists add a special dye to water samples brought back to the research ship. The dye turns red, with the shade of red showing how much the bacteria and zooplankton in the water are respiring.

Our Climate is Warming, and so is the Ocean

As Earth’s climate warms, the ocean is feeling the heat too, and this is causing some big changes [5]. Since 1960, ocean oxygen levels have dropped by about 2%. While this might not seem like much, it is a big deal for marine life! There are several reasons for this decline, but the main one is that, when surface waters warm up, it becomes harder for these oxygen-rich waters to mix with the colder, oxygen-poor waters below. Warm water is lighter than cold water, so it stays near the surface instead of sinking. Without this mixing, the deeper waters cannot get refreshed with oxygen from the air. Plus, in warmer waters, organisms tend to breathe faster, just like a dog breathes more quickly when it is hot. So, higher temperatures may cause an increase in respiration, using up more oxygen each day.

On the other hand, this reduction in oxygen could slow down respiration for some animals. This means that energetic fish, like sharks and tuna, may have to swim slower or even move to new areas where there is more oxygen. In extreme cases, some creatures might not survive at all. This is why scientists are concerned, climate change could make it harder for mesopelagic creatures to breathe and could shrink the areas of the ocean that have enough oxygen for marine life to thrive. This could have a big impact on life in the ocean.

How Can Scientists Work Together to Understand Respiration in the Mesopelagic Ocean?

To properly understand what is happening in the mesopelagic ocean, scientists from around the world are working together. By sharing knowledge, equipment, and results, we can get a clearer picture of what is happening in the ocean. It is also essential to establish a standard method for collecting and sharing data, so it can be easily accessed and analyzed by both humans and computers. This teamwork is crucial for protecting the ocean and its creatures. Our research group did exactly that, with support from the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research, we formed a group to study respiration in the mesopelagic ocean. This collaboration brought together scientists from 14 countries, and we collected data from many more researchers to better understand how mesopelagic creatures will be affected by climate change. The scientists called the group ReMO, which is the acronym for Respiration in the Mesopelagic Ocean.

What Can You do to Help Animals Continue to Breathe in the Mesopelagic Ocean?

Although we do not have all the answers yet, there are important actions you can take to help protect the animals living in the mesopelagic ocean. One big way is by reducing your carbon footprint. This means using less energy and supporting energy sources that release less CO2 into the air. By doing this, we can slow down global warming and help keep more oxygen in the ocean for marine life to breathe. You can also learn about and support efforts to protect the ocean from overfishing and deep-sea mining, as we still do not fully understand how these activities may harm mesopelagic creatures. Even small actions, like reducing waste and using less plastic, can make a significant difference in making our ocean healthy! Every step counts in protecting the ocean and all the amazing creatures that live there.

Glossary

Euphotic Zone: ↑ The sunlit upper layer of the ocean where enough light supports photosynthesis, allowing plants, algae, and many animals to live.

Chlorophyll: ↑ A green pigment found in plants, algae, and some bacteria that allows them to absorb light energy for photosynthesis.

Ocean Trench: ↑ A long, narrow, steep sided channel in the seafloor forming the deepest parts of the ocean.

Mesopelagic Zone: ↑ A darker, cooler ocean zone below the sunlit waters, home to animals adapted to low light, such as squid, lanternfish, and glowing creatures.

Electron Transport System: ↑ A cluster of chemicals that exists in all cells, which allow the cell to convert organic matter into energy.

Organic Matter: ↑ Chemicals that contain carbon and that have come from the remains of plants and animals.

In Situ: ↑ A Latin phrase that means in the natural or original place instead of being moved to another place.

Enzyme: ↑ A substance produced by a living creature that helps a chemical reaction to occur or to occur faster than it would in the absence of the enzyme.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work contributes to the objectives of the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR) working group 161 Respiration in the mesopelagic ocean; reconciling ecological, biogeochemical and model estimates (ReMO), and was supported by funding to SCOR from its national committees and from a grant to SCOR from the U.S. National Science Foundation (OCE-2140395). During the writing of this manuscript, CR was funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) projects MicroRESPIRE NE/X008630/1 and PARTITRICS NE/Y004264/1, and XAAS and JA were funded by the Spanish e-IMPACT project (PID2019-109084RB-C21 and -C22). The work of XAAS and JA was funded by the European Union under grant agreement no. 101083922 (OceanICU) and UK Research. MB was funded by the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), under grant ANR-23-CE01-0023 (project adhoC). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. Many thanks to Maisie Evans (PhD student at the University of East Anglia, UK) for her help with reviewing an early version of the manuscript.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

[1] ↑ Sardet, C. 2015. Plankton - Wonders of the Drifting World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 224. Available online at: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/P/bo19415930.html (Accessed November 30, 2025).

[2] ↑ Sigman, D. M., and Hain, M. P. 2012. The biological productivity of the ocean. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 3:21. Available online at: https://earth-system-biogeochemistry.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Sigman_and_Hain_2012_NatureEdu.pdf (Accessed January 21, 2026).

[3] ↑ Costello, M. J., and Breyer, S. 2017. Ocean depths: the mesopelagic and implications for global warming. Curr. Biol. 27:R36–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.11.042

[4] ↑ Turner, J. T. 2015. Zooplankton fecal pellets, marine snow, phytodetritus and the ocean’s biological pump. Prog. Oceanogr. 130:205–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2014.08.005

[5] ↑ Sarmiento, J. L., Slater, R., Barber, R., Bopp, L., Doney, S. C., Hirst, A. C., et al. 2004. Response of ocean ecosystems to climate warming. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 18:GB3003. doi: 10.1029/2003GB002134