Abstract

Food does more than keep us alive—it shapes our health and the health of the planet. Around the world, obesity rates are rising faster than ever, partly because of the spread of ultra-processed foods (UPFs)—packaged products like chips, processed meats, cookies, and sugary drinks that are cheap, convenient, and hard to resist. Eating too many UPFs can lead to obesity and other health problems, while producing them harms the environment through pollution, deforestation, and greenhouse gas emissions. Climate change and soil loss are making it harder to grow the foods our bodies need. These problems are connected, but so are their solutions: eating healthy, plant-based foods, building fairer food systems, and learning how food choices affect the world around us. In this article, we describe the surprising connections between climate change and obesity, explaining their shared causes, consequences, and solutions—and how your generation can help to make things better.

Food, Health, and the Planet

What is your favorite meal? Whether it is pizza, burgers, your grandma’s famous chicken, or beans and rice, chances are it tastes great and is often shared with your family or friends. A birthday cake can mark a special day. A bowl of soup can help you feel better when you are sick. Food is at the center of human life and how we socialize.

Eating the right foods in the right amounts gives you energy and helps you grow, while eating too much, or eating lots of unhealthy foods, can make people overweight or even lead to obesity. While you might have heard about the dangers of obesity, did you know that your food choices can affect more than just your body? The way food is grown, processed, and transported also affects the planet. So, when people eat too much or eat the wrong kinds of foods, it can harm both their bodies and the planet!

Obesity—A Growing Public Health Crisis

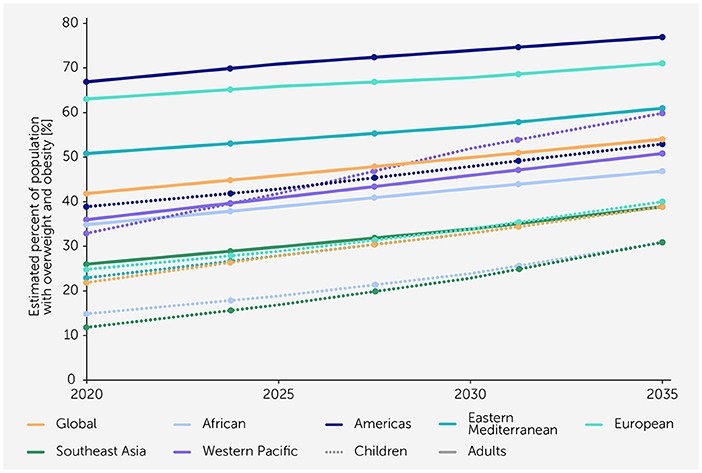

Globally, the number of people living with obesity has tripled since 1975. In 2022, more than one billion people were obese, including over 150 million children [1]. If current trends continue, scientists project that by 2035, nearly one in four people on Earth could be obese (Figure 1).

- Figure 1 - Obesity rates are rising all over the world.

- Solid lines show the estimated numbers of obese adults from 2020 to 2035, while the dotted lines illustrate obesity in children.

Rising obesity rates are a major public health crisis. Carrying too much fat affects nearly everything in the body. Obesity can make it harder for the body to control blood sugar, which increases the risk of diabetes. Extra weight strains the heart and blood vessels, raising the chance of heart disease and strokes. The joints in the knees and hips can wear down faster when they have more weight to carry. Also, some types of cancer are more common in people with obesity [2]. All these health problems cause disability, shorten lives, and place heavy costs on families and healthcare systems—costs that cannot be sustained in the long term.

More children than ever are living with obesity (Figure 1), raising concerns about their health as they grow up [3, 4]. In addition to the health problems mentioned above, obesity can also affect growth, make it difficult to be active, and even disrupt sleep. Children with obesity may face bullying, anxiety, or low self-confidence, and they may struggle in school. Because childhood obesity often continues into adulthood, its effects can shape a person’s whole life.

What Causes Obesity?

Obesity is a disease—it does not happen simply because someone eats too much or moves too little, and it is not a matter of personal choice or weak willpower [5]. It is more helpful to think of obesity as a problem for societies to solve together, rather than something that individuals should be blamed or shamed for. Many factors shape whether a person develops obesity, including their biology and the food choices available to them. Genes and daily habits, such as how much time people spend moving or sitting, can certainly play a role, but these influences alone cannot explain why obesity rates have risen so sharply.

Rising obesity is closely linked to the rapid spread of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) [6]. UPFs include packaged products like chips, cookies, processed meats, sugary drinks, and instant noodles. They are frequently designed to be cheap, convenient, and extremely appealing—often by combining sugars, fats, and flavor additives in ways that make people want to keep eating, even when they are full. Many UPFs also contain chemical additives—such as colorings, sweeteners, preservatives, and flavor enhancers—that may have harmful effects of their own. Eating a diet high in UPFs makes it easy to consume more energy than the body needs, while leaving people less satisfied and more likely to overeat.

Shared Causes: How Foods are Made and Eaten

Obesity and environmental harm may seem like separate problems, but they are both shaped by the ways foods are produced and eaten. Healthy diets—based on fresh fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains—are good for people and for the planet. These foods provide critical nutrients while using fewer resources and creating less greenhouse gas emissions than many packaged products.

In contrast to these healthier options, today’s food systems often favor unhealthy, ultraprocessed animal and plant products because they are cheap to make and easy to store and transport. The animal ingredients in UPFs, like powdered milk, are by far the worst for the environment and produce an enormous amount of greenhouse gases. Raising animals for food is a major cause of biodiversity and habitat loss, along with water and air pollution. Producing UPFs requires large amounts of corn, wheat, and soy, often grown in huge single-crop fields that wear out soil, rely on fertilizers and pesticides, and further reduce biodiversity. Processing, packaging, and shipping UPFs also require energy and water and release greenhouse gases.

Because UPFs are cheaper and often more widely available than fresh fruits and vegetables or homemade meals, they have quickly taken over diets in many parts of the world. Families with lower incomes are more likely to live in food deserts—communities where fresh, healthy foods are expensive or not available at all. These areas may also be food swamps, where fast food restaurants are everywhere and UPFs crowd out healthier options on supermarket shelves. Big food companies worsen the problem by making their products “addictive” and aiming their ads at kids, hooking them on UPFs while they are young and setting unhealthy eating patterns that may last a lifetime. All these problems create a cycle where the same foods that drive obesity also put heavy stress on the environment.

Shared Consequences: How People and The Planet Suffer

As obesity rises, people clearly get sicker… but how does this make the health of the planet worse? Larger bodies require more energy to function, so if more people are living with obesity, extra food must be produced to feed them. Scientists estimated that between 1975 and 2014, weight gain across the world added about 13% more food energy needs, equal to feeding 286 million extra adults [7]! This extra food production generated about 20% more greenhouse gas emissions, mostly from farms and factories. These effects could speed up climate change and threaten ecosystems with more pollution.

At the same time, environmental damage makes it harder for people to eat well. Our current patterns of food production and consumption are not sustainable: if we continue to exhaust soils, clear forests, and drive climate change, food shortages and rising costs will affect both people and economies worldwide. When fruits, vegetables, and grains become harder to grow or more expensive, communities start to rely on cheap UPFs—adding to the risk of obesity and poor nutrition. As we mentioned, these problems are often hardest on vulnerable groups, like families with low incomes—many of whom are also more likely to live in places hit hard by climate change, such as areas with extreme heat or flooding.

Shared Solutions: Changing Diets, Systems, and Minds

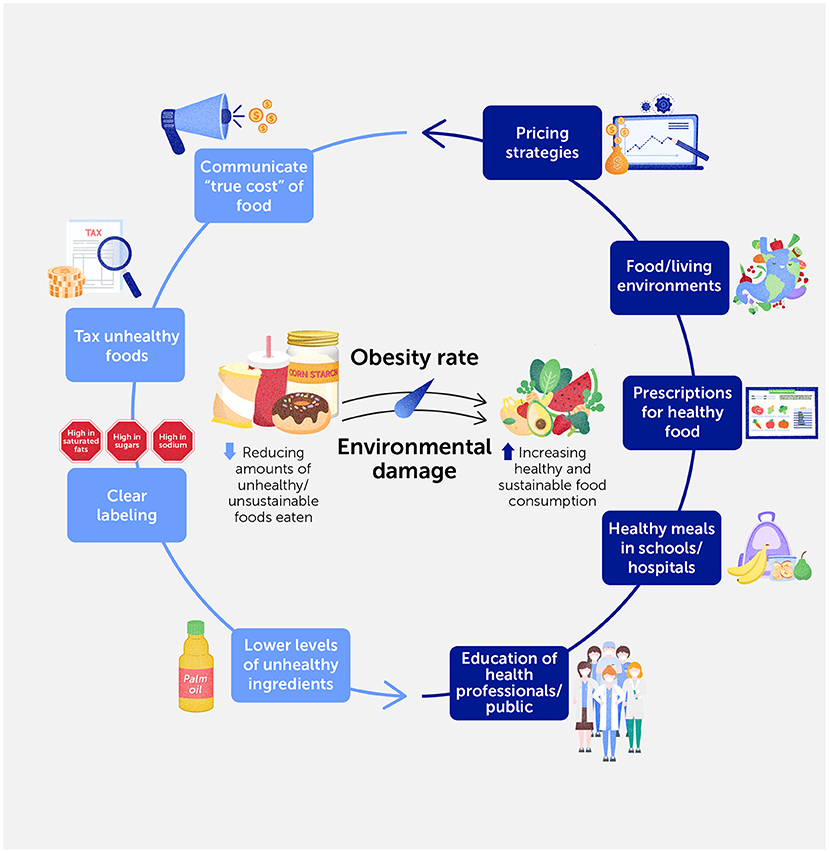

Obesity has many causes, which means it takes more than individual choices to solve it. The good news is that, as consumers, we often have the power to shift what we eat, ultimately changing how food is produced and sold. Learning about the connections between nutrition and the environment can lead to shared solutions—benefits for both people and the planet (Figure 2).

- Figure 2 - Changing what we eat, how food is produced and sold, and what we learn about nutrition and the environment can help to both reduce the obesity rate and limit environmental damage.

Changing Diets

One of the most powerful solutions lies in the foods we eat every day. Diets rich in fresh, healthy foods give the body the energy it needs, and these foods also tend to be less damaging to the environment than UPFs. Shifting diets away from UPFs and toward more natural, plant-based options can lower the risk of obesity while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions, water use, and packaging waste. Changing our diets does not mean the same thing everywhere. In high-income countries, eating fewer UPFs and less red meat could bring major health and environmental benefits. Producing red meat often involves cutting down forests to raise cattle or grow animal feed, releasing greenhouse gases and reducing biodiversity [8]. In low- and middle-income countries, the priority may be to improve access to nutrient-rich foods, so that people can meet their energy needs without relying on UPFs. In both cases, healthier diets for people also translate into healthier outcomes for nature.

Fairer Food Systems

Our individual choices as consumers matter, but those choices depend on what foods are easy for each person to find and afford. Right now, UPFs are everywhere—in grocery stores, corner shops, and fast-food restaurants. Fresh, healthy, plant-rich foods, on the other hand, may be expensive, seasonal, or completely unavailable in some neighborhoods.

Making food systems fairer means changing the rules so that healthier choices, like buying fresh foods locally, are also the easier and cheaper ones. How? Governments can pass laws to help lower the price of fresh, nutritious foods so they are more available and affordable. Local markets and community programs can be created to bring fruits and vegetables closer to families—especially in food deserts and food swamps. Clear nutrition labels could be required, to warn people about high levels of sugar, fat, or salt; and climate labels could show a food’s impact on the environment. Governments can also introduce taxes on sugary drinks and limit advertising of UPFs—especially ads aimed at kids. Some countries have already done this. Step by step, these changes can build food environments that lower obesity and make the planet healthier.

Education and Awareness

Education is key to making changes, and more education about nutrition and the environment is needed. In schools, children can learn about the importance of plant-rich diets and the hidden risks of UPFs, including how some of these foods are engineered to make people crave more. Health professionals can guide families toward affordable, nutritious options including healthy alternative sources of protein and minerals for children who wish to avoid meat or dairy. TV ads and online messages can focus on how food choices affect the climate and ecosystems we all depend on. Together, these efforts can help people understand the bigger picture and encourage healthier actions.

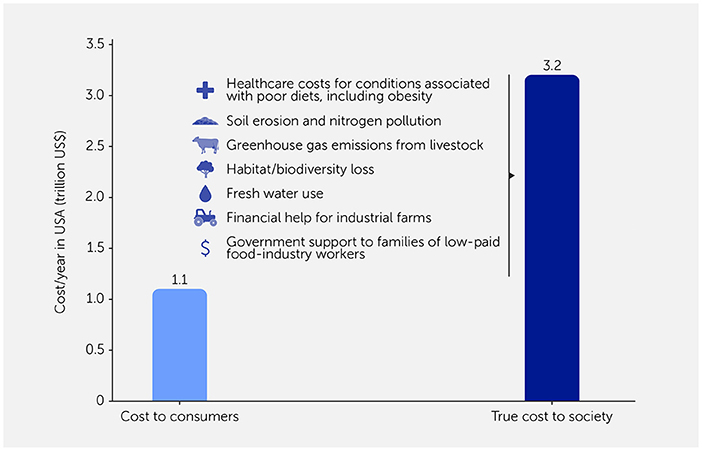

Part of this education involves understanding the true cost of food. The price tag on a bag of chips or a sugary drink only shows what it costs to buy. It does not include the costs of treating obesity, cleaning up pollution, or repairing damage to the climate caused by the food. Very low-cost foods produced in some countries may also use slave or underpaid labor in the agricultural process, not unlike what is seen in the fashion industry. When we add up these hidden costs, many UPFs turn out to be far more expensive for society than healthier foods (Figure 3). Learning about the true cost of food can help people see why changing their diets might be a great idea.

- Figure 3 - The price tags on foods only tell us what those foods costs consumers to buy.

- However, the true cost can be much higher, as it involves factors like the costs of treating obesity, cleaning up pollution, repairing climate damage caused by the food, and financial help for farmers and food-industry workers—as shown by the increased height of the dark blue bar.

A Healthier Future Starts With You

Obesity and environmental damage are two of the biggest challenges of our time, and food lies at the center of both. Young people are especially affected, since childhood obesity is rising quickly and climate change will shape the world you and your friends inherit.

However, these challenges also give young people a unique chance to make a difference. By asking questions about why UPFs are so widely marketed and seem almost impossible to stop eating, and why healthy food often costs more, young people can spark important conversations that can spread through families, schools, and communities—helping to build momentum for change. When young people challenge the systems that shape which foods are available and affordable, they are contributing to shared solutions for the health of the planet and all its people.

Glossary

Obesity: ↑ A disease in which too much body fat builds up over time, making it harder for the body to stay healthy and increasing the risk of other illnesses.

Diabetes: ↑ A disease in which the body cannot properly control blood sugar levels, often because it does not make or use enough insulin.

Stroke: ↑ A medical emergency that happens when blood flow to part of the brain is blocked, causing brain cells to die and sometimes leading to lasting damage.

Ultra-Processed Foods (UPFs): ↑ Packaged foods like chips, cookies, processed meats, and sugary drinks that are made with many added ingredients and designed to be cheap, convenient, and very tasty.

Biodiversity: ↑ The variety of living things on Earth—including animals, plants, and microorganisms—that work together to keep ecosystems healthy and balanced.

Food Desert: ↑ An area where fresh, healthy foods like fruits and vegetables are hard to find or too expensive for many people to buy.

Food Swamp: ↑ A place where unhealthy foods like fast food and snacks are easy to find, while healthier options are rare or costly.

True Cost: ↑ The real overall cost of something, including hidden effects such as pollution, health problems, and damage to the environment—not just its price in the store.

Conflict of Interest

JCGH has consultancies with Dupont IFF and Allurion. All payments go to the University of Leeds to support research. These companies were not involved in any way in the preparation of the present article.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Edited by Susan Debad Ph.D., graduate of the UMass Chan Medical School Morningside Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (USA) and scientific writer/editor at SJD Consulting, LLC. We would like to thank the coauthors of the original manuscript: Catherine M. Champagne, Marj Moodie, Joseph Proietto, and Guy A. Rutter. Paul Behrens was supported by a British Academy Global Professorship and is REAPRA senior fellow.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Original Source Article

↑Behrens, P., Champagne, C. M., Halford, J. C. G., Moodie, M., Proietto, J., Rutter, G. A., et al. 2025. Obesity and climate change: co-crises with common solutions. Front. Sci. 3:1613595. doi: 10.3389/fsci.2025.1613595

References

[1] ↑ World Obesity Federation. 2023. World Obesity Atlas 2023. London, UK: WOF. Available online at: https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/WOF-Obesity-Atlas-V5.pdf (Accessed December 1, 2025).

[2] ↑ Kyrgiou, M., Kalliala, I., Markozannes, G., Gunter, M. J., Paraskevaidis, E., Gabra, H., et al. 2017. Adiposity and cancer at major anatomical sites: umbrella review of the literature. BMJ. 356:j477. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j477

[3] ↑ NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). 2024. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 403:1027–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2

[4] ↑ Simmonds, M., Llewellyn, A., Owen, C. G., and Woolacott, N. 2016. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 17:95–107. doi: 10.1111/obr.12334

[5] ↑ Rubino, F., Cummings, D. E., Eckel, R. H., Cohen, R. V., Wilding, J. P. H., Brown, W. A., et al. 2025. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 13:221–62. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00316-4

[6] ↑ Dicken, S. J., and Batterham, R. L. 2024. Ultra-processed food and obesity: what is the evidence? Curr. Nutr. Rep. 13:23–8. doi: 10.1007/s13668-024-00517-z

[7] ↑ Vásquez, F., Vita, G., and Muller, D. B. 2018. Food security for an aging and heavier population. Sustainability. 10:3683. doi: 10.3390/su10103683

[8] ↑ Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., et al. 2019. Food in the anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 393:447–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4