Abstract

Temperatures are increasing almost everywhere on Earth due to climate change. To understand what hotter temperatures will mean for tropical rainforests, researchers are studying the trees and other plants growing around the Boiling River in the Peruvian Amazon. At the Boiling River, hot waters warm the surrounding area, creating the hottest forest on Earth and making a unique, natural warming experiment. In our recent study, we found that many types of trees do not grow in the hotter forests, and as a result, the number of tree species in the hotter forests is much lower than in the cooler, normal forests. The research at the Boiling River provides important evidence that rising temperatures can have a negative effect on tropical forests, and that global warming could cause many tropical tree species to go extinct.

A River that Boils?!?

Imagine a river so hot that it actually boils! This may sound like something out of a fantasy novel, but believe it or not, this is a real place in the Amazon rainforest (Figure 1). It is called the Boiling River. This special place in Peru is helping scientists understand what might happen to tropical rainforests around the world as the Earth gets warmer due to climate change.

- Figure 1 - The Boiling River and the surrounding forest (Photo credit: K. J. Feeley).

What Makes the Boiling River so Special?

The Boiling River, known locally as Shanay-Timpishka in the indigenous Asháninka language, translates to “boiled by the heat of the sun”. However, the river’s heat does not actually come from the sun. Instead, the heat comes from deep within the Earth. Hot water from underground flows up into the river, raising the water temperature to a scorching 95°C (over 200°F) in some places. That is hot enough to cook an egg! The hot water does not just heat the river; it also heats the air around the river and in the nearby forests. This means that the forests surrounding Peru’s Boiling River are some of the hottest forests on Earth.

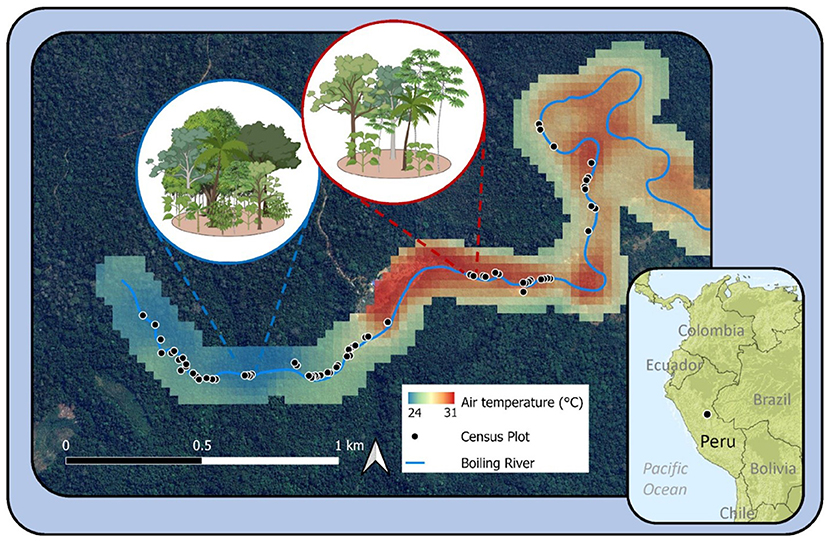

As the hot water flows along the river’s 6-km (4-mile) course, it mixes with cooler water. This creates a range of different water temperatures, which in turn creates different air temperatures in the surrounding forests (Figure 2). The closer you are to where the hot water bubbles up from the ground, the hotter the forest is, and the farther away you are, the cooler it is. These differences in temperatures create a kind of natural warming experiment.

- Figure 2 - A map of the Boiling River in Peru’s Amazon rainforest, showing the average annual air temperatures measured in the forest along the river, the locations of the forest census plots from our study, and cartoon depictions of how the forest differs between the cooler (blue) and hotter (red) areas.

A Natural Laboratory for Climate Change Research

This natural warming experiment is a very important and unique “living laboratory” for scientists to study climate change. Because there is such a wide range of temperatures in just a small area, scientists can observe how plants, animals, and even tiny microbes respond to different temperatures [1].

The hot air temperatures around the Boiling River are similar to what scientists predict will happen in the rest of the Amazon by the year 2100 because of climate change. By studying how plants are dealing now with the hot temperatures at the Boiling River, scientists can get an idea of how the Amazon and other rainforests may change in the future. This research is essential because the rainforest is a critical part of our planet. It is home to countless species of plants and animals and helps to regulate Earth’s climate.

New Research at the Boiling River

Recently, our team, which included scientists from Peru and the United States, conducted a study looking at the trees and other plants in the forests surrounding the Boiling River. We wanted to understand how hot soil and air temperatures affect the variety and types of trees that live there.

We hiked along the river’s edge and set up 70 small plots in the forest where we could census and study the plants. Each of these plots had a slightly different average air temperature, ranging from about 24.0 to 26.5°C (about 75–80°F; Figure 2). In each of these forest census plots, we carefully counted, measured, and identified every tree and shrub that was larger than 2 cm (0.8 inches) in width. This required a lot of hard work and careful observation. In total, we identified and measured over 600 trees from nearly 200 different species!

We did not just look at the trees in the forest. We also used information from plant collections, called herbaria (plural for herbarium), and online databases. This allowed us to figure out where each of the plant species typically grows and to estimate what temperatures each species normally prefers.

What did we Discover?

Our research team made some very important discoveries about how hot temperatures affect the forests around the Boiling River. Here are two of the main things that we found.

Less Diversity in Hotter Areas

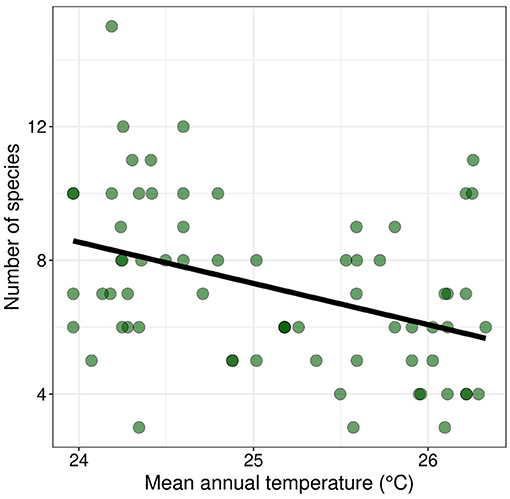

One of the most important findings of our study was that the diversity of trees was much lower in the hotter forests. In fact, for every 1°C increase in average air temperature (about 1.8°F), the number of trees growing in the plots decreased by more than 10%! Overall, the hottest forests at the Boiling River had 33% fewer types of trees than the cooler forests, even though these forests were only separated by a short distance of about 2 km (about 1.2 miles; Figure 3). This drop in tree diversity suggests that as rainforests get hotter and hotter due to climate change, there could be a rapid loss of many plant species.

- Figure 3 - The number of tree species per plot (y-axis) is lower at hotter average air temperatures than at cooler air temperatures (x-axis).

- The black line shows this trend of decreasing diversity at hotter temperatures that was calculated using our observations (green dots) of plants in the forest plots along the Boiling River.

A Change in the Types of Trees

We also found that the types of trees growing in our forest plots changed depending on the temperature. Plots in hotter areas had a higher number of thermophilic species—those that are adapted to living in warmer conditions. These heat-loving plant species tend to grow in the hotter parts of the Amazon. In contrast, the cooler forests along the Boiling River had mostly plant species that typically only grow in the cooler parts of the Amazon. Other studies at the Boiling River have also shown that many plants cannot easily adjust to higher temperatures and therefore may suffer when it gets hotter [2, 3]. These findings all suggest that as global temperatures continue to rise due to climate change, rainforests could become dominated by only the heat-loving tree species, while the other species that are less tolerant of heat may grow slower and decrease in abundance—or some species may disappear altogether!

Why does this Matter?

Even small changes in the diversity and types of trees growing in the forest could have big impacts on rainforests, and even the entire planet. Changes in the types of plants could affect the animals that depend on them for food and shelter. If certain plant species disappear, the animals that rely on those plants could also decline or disappear, which could disrupt the entire food web. Further, changes in the diversity and types of trees growing in the forest could affect the rainforest’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Rainforests play an important role in regulating Earth’s climate by absorbing carbon dioxide, which is a greenhouse gas that strongly contributes to climate change. If warming harms the trees, it could reduce the rainforest’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide and make climate change even worse. Understanding these changes is really important for developing effective ways to protect rainforests and the many species that live there.

The Boiling River and the Future of Rainforests

Our research at the Boiling River provides valuable information about what might happen to rainforests as the Earth gets hotter. This information can be used to develop better strategies for protecting rainforests and other ecosystems. One thing to keep in mind is that the forests around the Boiling River have had thousands of years to get used to hot temperatures. Other parts of the Amazon have never been this hot and are now warming very fast. These rapid changes may make it even harder for plants to survive.

In short, the Boiling River is an amazing place that helps scientists to understand and predict the potential impacts of climate change on plants and trees in the rainforest [1]. The research being done in this region will help us to protect rainforests and the many plants and animals that depend on healthy forests. It also emphasizes the need for even more studies, with other species and in different ecosystems, to fully understand how climate change is impacting the natural world. By learning from the studies at Peru’s Boiling River, we can make better decisions about how to conserve and protect Earth’s important ecosystems.

Glossary

Rainforest: ↑ A type of forest with lots of rain all year. Rainforests are typically found in hot climates in the tropics near the equator. The Amazon is Earth’s largest rainforest.

Census: ↑ A count of all the individuals and species in a particular plot or place.

Herbarium: ↑ A collection of dried leaves and plants that are used for scientific study.

Diversity: ↑ How many different kinds of organisms or species are in a certain area.

Thermophilic: ↑ Adapted to live in warmer conditions.

Ecosystem: ↑ A type of habitat where living things like plants, animals, and fungi all interact with each other and with their environment.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research at the Boiling River was supported by a grant from the US National Science Foundation (Award DEB 2344948).

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Original Source Article

↑Fortier, R. P., Kullberg, A. T., Soria Ahuanari, R. D., Coombs, L., Ruzo, A., and Feeley, K. J. 2024. Hotter temperatures reduce the diversity and alter the composition of woody plants in an Amazonian forest. Glob. Change Biol. 30:e17555. doi: 10.1111/gcb.17555

References

[1] ↑ Posch, B. C. 2024. How a boiling river is helping to highlight the risks of warming for tropical forests. New Phytol. 241:1381–3. doi: 10.1111/nph.19515

[2] ↑ Kullberg, A. T., Coombs, L., Soria Ahuanari, R. D., Fortier, R. P., and Feeley, K. J. 2024. Leaf thermal safety margins decline at hotter temperatures in a natural warming ‘experiment’ in the Amazon. New Phytol. 241:1447–63. doi: 10.1111/nph.19413

[3] ↑ Kullberg, A. T., and Feeley, K. J. 2024. Seasonal acclimation of photosynthetic thermal tolerances in six woody tropical species along a thermal gradient. Functional Ecol. 38:2493–505. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.14657