Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is already part of everyday life, recommending music, translating languages, and even helping with homework. But scientists want AI to do even more demanding jobs, such as guiding self-driving cars, helping doctors with medical scans, or steering rescue drones in dangerous places. The problem is that today’s computers were not built for nonstop learning and rapid decision making. They hit the “memory wall”, a slowdown that happens when computers waste time and energy moving data around instead of working on it. To get past this, researchers are looking to the human brain for inspiration. Brain cells called neurons can handle information, connect in networks that learn, and send short bursts of signals that save energy. New types of computer chips copy these ideas to make AI faster and more efficient. These advances could cut the energy computers use and open the way for faster, greener technology.

AI Needs Faster, Smarter Computers

Not long ago—just a few decades—artificial intelligence (AI) was mostly something we only heard about in science fiction movies, where it piloted spaceships or controlled a robot sidekick. But now, chances are you interact with AI in your daily life, maybe without even realizing it. YouTube and Spotify use AI to recommend videos or songs based on your past choices, Google Translate uses it to convert words into different languages, and platforms like ChatGPT can answer questions, create art, write stories, or help with homework.

The impressive things that AI tools already do require lots of computer power. Researchers are now working toward even more demanding uses of AI, such as systems that can guide self-driving cars through busy streets, assist doctors in accurately diagnosing diseases from medical scans, or control rescue drones after a natural disaster. In situations like these, the AI system must see, plan, and act almost instantly—there is no time to wait for a slow computer to respond. Many of today’s computers were built for tasks like running apps, watching videos, writing documents, browsing the internet, or running spreadsheets—jobs that do not require the level of computer power that AI needs. AI requires handling massive amounts of data at high speed and doing so continuously as it learns and makes on-the-spot decisions. The mismatch between what AI needs to function in high-stakes situations and what computers can currently deliver without using too much energy is one of the biggest challenges facing scientists and engineers today [1].

Why Today’s Computers are Too Slow for AI

To understand the problem, it will help to look at how today’s computers are organized. Every computer has two main “parts”: hardware and software. Hardware is the physical machinery—chips, circuits, and wires. Software is a set of instructions that tells the hardware what to do and when to do it, whether that is running a game, editing a photo, or sending a text message. When people think about AI, they often focus on the software—the programs that translate language or recognize images. But software can be limited by hardware, because the physical chips and circuits inside the computer determine how quickly and efficiently those programs can run.

Why does the hardware slow things down? Typical computer hardware has two main components: one that stores information, which is called memory, and one that carries out instructions in the form of calculations, which is called the processor. Every time the processor needs a piece of information, it must fetch it from memory before doing anything with it (Figure 1A). You can think about this like trying to do your math homework when your calculator is on your desk in the math classroom but all the data you need for your calculations is across the hall in the library. Every time you need some numbers, you need to stop working, run to the library, and bring the data back. The constant back-and-forth slows you down and burns a lot of energy (Figure 1B).

- Figure 1 - (A) Computer hardware has two main components: the memory, where information is stored, and the processor, which carries out the calculations.

- In typical computers, the processor much fetch information from memory every time it carries out its instructions. This is called the memory wall problem, and it can make traditional computers too slow for AI systems. (B) The memory wall problem is like trying to do your math homework at your desk, but each time you need a piece of information you must run across the hall to the library to get it, slowing you down and burning lots of energy.

While most everyday computer tasks only need to move small amounts of data at a time, AI puts much greater demands on hardware. AI systems contain millions or even billions of pieces of information that must be checked over and over to spot patterns or make decisions. The constant shuttling of data between memory and processor creates a major slowdown inside the computer. Researchers call this the memory wall problem [2]. Even if the processor is ready to work, it spends most of its time waiting for data to arrive. The result is wasted energy and slower performance—two things AI cannot afford when it needs to act quickly in the real world. Another important factor is how much memory is used to store each piece of information. Computers usually give every piece the same amount of digital space in memory, like handing everyone the same big box no matter how small their item is. This wastes memory and can slow down AI.

Learning From the Brain

In terms of computing power and memory management, the human brain is far more efficient than any computer we can build today. Scientists are now taking lessons from the brain as they try to overcome the memory wall problem. Brain cells called neurons are especially important for processing signals from the world and the body—like sights, sounds, touches, movements, and even memories. There are three big features that make brain neurons different from traditional processors.

First, neurons can both store and process information. Each neuron receives tiny electrical or chemical signals from other neurons. It adds up all the incoming signals, decides whether the message is strong enough to pass along, and if it is, sends its own signal to other neurons. Neurons also store information by strengthening or weakening their connections with other neurons, which are called synapses. This means a single neuron can both processes signals and store memories without constantly moving data back and forth the way traditional computer hardware does. This efficient way of representing and handling data saves memory and makes information transfer faster.

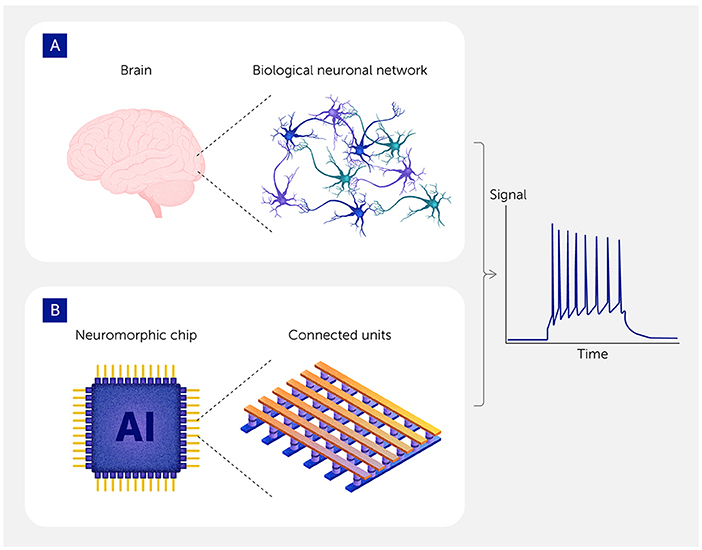

Second, neurons form flexible networks that can change and learn (Figure 2A). The brain’s power comes from billions of neurons working together. One neuron by itself cannot do much, but a vast network of neurons can recognize a friend’s face, understand speech, or plan a movement. These networks constantly change as connections between neurons grow stronger or weaker, which is how the brain learns from experience. In contrast, conventional computer circuits cannot change their connections on their own.

- Figure 2 - (A) Neurons in the brain are organized into networks that can both store and process information based on the strength of their connections to each other.

- The connections between neurons can change in number and strength, which is how the brain learns from experiences. Neurons also communicate by sending “spikes” of signals only when necessary, which saves energy. (B) To overcome the memory wall problem so that AI systems can work faster and more efficiently, engineers are trying to design faster computer hardware, called neuromorphic chips, made of connected units that combine memory and processing, have brain-like flexible connections, and use spike-based computing.

Third, neurons send signals only when needed. Instead of streaming information nonstop like today’s computer chips, neurons send quick bursts of electrical activity, called spikes, only when something important needs to be shared—like a short ping that says “pay attention!”. This stop-and-go style of communication saves enormous amounts of energy while still allowing the brain to react quickly to the world. Computer scientists call this idea spike-based computing when they try to copy it in machines.

Together, these three features make the brain powerful and energy efficient. Engineers hope that by borrowing some of these strategies, they can design computer hardware that handles AI tasks quicker and with far less energy. At the same time, computer scientists and software engineers will need to develop new software so that these new hardware solutions can reach their full potential.

Brain-Inspired Computing for Smarter Hardware

One step toward brain-inspired computing is compute-in-memory (CiM). CiM is a new technology that takes inspiration from the first key characteristic of brain neurons: combining memory and processing in the same physical hardware [3, 4]. Instead of keeping storage and calculation separate, as today’s chips do, CiM-based chips are designed to carry out simple calculations, such as adding or multiplying numbers, within the memory itself, right where the data is stored. This is similar to the way neurons both hold information and process signals. In our math homework analogy, CiM is like moving your calculator into the library so you can look up numbers and work on them without constantly running back and forth. By cutting out extra data transfers, CiM chips could make AI systems faster and more efficient.

Neuromorphic chips take this a step further [5]. The word “neuromorphic” means “shaped like the brain”, and these chips are built from many tiny units that act like simplified versions of the brain’s neurons and synapses (Figure 2B). Each unit can send and receive signals, adjust the strength of its connections with other units, and communicate with short bursts (spikes) of activity only when new information arrives—similar to how brain cells work. Linking thousands or even millions of these units together creates a network that can learn from patterns and adapt to new situations. Researchers are also creating spiking neural networks (SNNs), special AI programs (software) built to match this hardware [6, 7]. In contrast to ordinary computing, which processes information with constant signals, SNNs are designed to work with spikes. The simultaneous optimization of hardware and software could solve problems in real time, such as recognizing images, speech, or movement as they happen—while using far less energy than today’s chips.

These brain-inspired chips also use a technique called quantization, which stores data in simpler, smaller pieces so the computer can work faster without losing important details. Quantization reduces memory needs and speeds up processing with only a small loss in accuracy. Together, compute-in-memory, neuromorphic design, and quantization help create smarter hardware that works faster and more efficiently—much like the human brain.

Both CiM and neuromorphic chips are still in the research stage. CiM may be closer to real-world use, while neuromorphic chips represent a longer-term goal that could one day enable brain-like computing—but both show how lessons from biology could help us design computers that could support more powerful AI. Training today’s most advanced AI systems can use as much electricity as hundreds of households in a year, on top of the huge amounts already consumed by data centers worldwide. Cutting this demand could make AI more practical and lower its negative impact on Earth’s climate. Researchers see these advances as steps toward what they call a converged platform—a single kind of hardware that can run today’s data-hungry AI while also supporting future, brain-like AI systems.

Smarter Hardware in Future Action

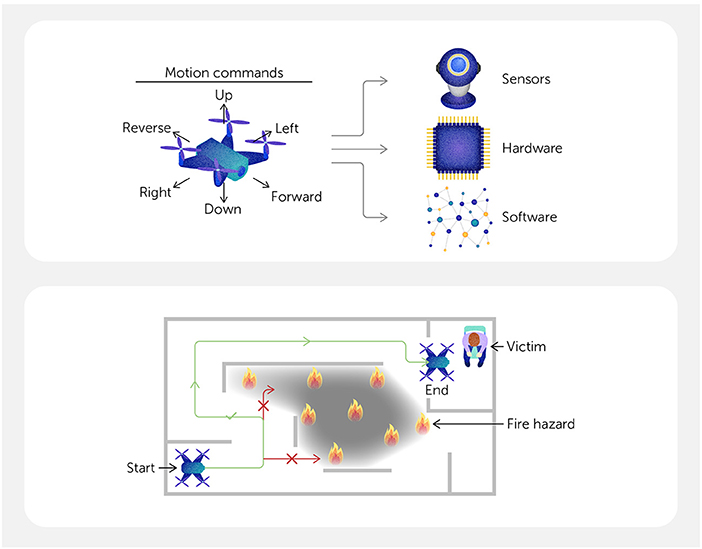

Think about a rescue drone flying into a collapsed building after an earthquake: every second counts. The drone’s onboard AI might be trained to fly into places that are too dangerous or too small for people to enter, map out safe routes for rescue workers, or even locate trapped survivors by scanning for heat or sound [8]. To succeed, the AI must process information from cameras and sensors, make decisions about where to go, and keep moving without delay (Figure 3). If its computer spends too much time stuck in the memory wall traffic jam, the drone could crash into debris, overlook signs of survivors, or fail to guide rescuers when every second matters.

- Figure 3 - An AI-powered rescue drone must process information from its sensors extremely quickly, so that it can maneuver precisely through dangerous places (like collapsed buildings) when every second counts.

New hardware ideas like CiM and neuromorphic chips, coupled with neuromorphic software such as spiking neural networks, could make this kind of life-or-death task possible, not only for drones but for many other uses. Phones and laptops could run advanced AI apps without draining their batteries or overheating. Self-driving cars could respond instantly to hazards on the road. Medical devices could process signals from the body in real time, helping doctors spot problems quickly. And large data centers—which power much of the world’s computing—could operate with far less energy. Although these designs are being developed mainly to support AI, they would also make many kinds of everyday computing faster and more efficient.

The Road Ahead

As AI becomes more central to our world, computers will need to process information accurately, quickly, and without wasting energy. Today’s hardware struggles with this task because of the memory wall problem, which happens because data spends too much time traveling between memory and processor. To overcome this problem, researchers are rethinking how computers should be built. Compute-in-memory chips store data where it is used, and neuromorphic systems borrow ideas from the brain’s networks of neurons. Both approaches aim to reduce wasted energy and allow AI to work in new, more demanding settings.

These technologies are mostly still in the research stage, and scientists and engineers face tough problems building them reliably, making them small and affordable enough for everyday devices, and showing they can handle the huge demands of modern computing. But progress is happening in both hardware and software. If these researchers succeed, the memory wall that limits computers today may become a thing of the past. That would mean faster, more efficient AI systems in areas from emergency response to medicine to everyday technology—and it would also reduce the energy burden of computing, helping to protect Earth’s changing climate as AI becomes an even bigger part of our world.

Glossary

Memory Wall Problem: ↑ A slowdown in computers caused by constant movement of data between memory and processor, which wastes time and energy.

Neuron: ↑ A brain cell that receives signals, processes them, and sends signals to other neurons while also storing information in its connections.

Synapse: ↑ The connection between two neurons where information is stored and passed along by changing the strength of the link.

Compute-in-Memory (CiM): ↑ A type of computer chip that can both store and process information in the same place, reducing wasted energy and speeding up tasks.

Neuromorphic Chips: ↑ Computer chips built from many small units that act like neurons and synapses, sending spikes and forming networks that can learn and adapt.

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs): ↑ Special AI programs designed to communicate with short bursts of activity, or spikes, similar to how neurons in the brain send signals.

Quantization: ↑ A technique that stores data in simpler, smaller pieces, reducing memory use and making computer processing more efficient.

Converged Platform: ↑ A single kind of computer hardware designed to run both today’s data-hungry AI systems and future brain-like AI programs.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Edited by Susan Debad Ph.D., graduate of the UMass Chan Medical School Morningside Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (USA) and scientific writer/editor at SJD Consulting, LLC. We would like to thank the coauthors of the original manuscript: Tanvi Sharma, Shubham Negi, Deepika Sharma, Utkarsh Saxena, Sourjya Roy, Anand Raghunathan, Zishen Wan, Samuel Spetalnick, and Che-Kai Liu. The research was funded in part by the JUMP 2.0 program [The Center for Co-design of Cognitive Systems (CoCoSys)], Semiconductor Research Corporation, National Science Foundation, Intel, and Department of Energy.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Original Source Article

↑Roy, K., Kosta, A., Sharma, T., Negi, S., Sharma, D., Saxena, U., et al. 2025. Breaking the memory wall: next-generation artificial intelligence hardware. Front. Sci. 3:1611658. doi: 10.3389/fsci.2025.1611658

References

[1] ↑ Horowitz, M. 2014. “1.1 Computing’s energy problem (and what we can do about it)”, in IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference Digest of Technical Papers (ISSCC), (San Francisco, CA: IEEE).

[2] ↑ Wulf, W. A., and McKee, S. A. 1995. Hitting the memory wall: implications of the obvious. ACM SIGARCH Comput Archit News. 23:10–20. doi: 10.1145/216585.21658

[3] ↑ Chang, M., Lele, A. S., Spetalnick, S. D., Crafton, B., Konno, S., and Wan, Z. 2023. “A 73.53 TOPS/W 14.74 TOPS heterogeneous RRAM in-memory and SRAM near-memory SoC for hybrid frame and event-based target tracking”, in IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), (San Francisco, CA: IEEE), 426–8.

[4] ↑ Agrawal, A., Ali, M., Koo, M., Rathi, N., Jaiswal, A., and Roy, K. 2021. IMPULSE: a 65-nm digital compute-in-memory macro with fused weights and membrane potential for spike-based sequential learning tasks. IEEE Solid State Circuits Lett. 4:137–40. doi: 10.1109/LSSC.2021.3092727

[5] ↑ Davies, M., Srinivasa, N., Lin, T.-H., Chinya, G., Cao, Y., Choday, S. H., et al. 2018. Loihi: a neuromorphic manycore processor with on-chip learning. IEEE Micro 38:82–99. doi: 10.1109/MM.2018.112130359

[6] ↑ Roy, K., Jaiswal, A., and Panda, P. 2019. Towards spike-based machine intelligence with neuromorphic computing. Nature 575:607–17. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1677-2

[7] ↑ Kosta, A. K., and Roy, K. 2023. “Adaptive-spikenet: event-based optical flow estimation using spiking neural networks with learnable neuronal dynamics”, in IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), (London, United Kingdom: IEEE).

[8] ↑ Wan, Z., Qian, J., Du, Y., Jabbour, J., Du, Y., Zhao, Y., et al. 2025. Generative AI in Embodied Systems: System-Level Analysis of Performance, Efficiency and Scalability. 26–37. doi: 10.1109/ISPASS64960.2025.00013