Abstract

Plants absorb various substances from the environment, such as water, minerals, and gases—all of which are made of chemical elements. Sometimes these elements are helpful for the plant, and sometimes they can be harmful. For example, grass species absorb a chemical element called silicon, from which they form microscopic glass-like layers that repel plant-eating animals. A recent study that we conducted showed that this ability could potentially reduce locust outbreaks. In the study, we also discovered that desert plants have a unique “chemical signature”, which holds some surprises. For example, desert plants can absorb large amounts of strontium. This element is likely beneficial to plants growing in harsh conditions. This property is of particular importance because we may be able to use plants such as these to clean up soil contaminated with radioactive strontium.

What is in a Plant?

Many plants look simple—consisting of a stem, leaves, and perhaps some flowers. But inside, plants are composed of lots of different materials called organic compounds. Most of a plant’s body, including its DNA, is made of organic compounds containing carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, with varying amounts of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur. These are the substances that control most of the plant’s biological activity. But plants can also contain many other chemical elements [1]. Some of these elements are part of the plant’s organic compounds and play key roles. For example, magnesium and iron participate in the photosynthesis process. Plants also have special openings called stomata, which allow gases such as carbon dioxide, oxygen, and water vapor to enter and leave the plant. Since the stomata are a significant source of water loss, the plant controls their opening and closing using potassium. Almost every element on the periodic table can be found inside a plant under one circumstance or another, unless the plant makes special efforts to prevent its entry.

What benefit do plants get from all these elements? This question led us to some surprising and intriguing discoveries. Sometimes a chemical element enters a plant almost by accident, hitching a ride with the water, without it “doing” anything in the plant or causing any benefit. In a plant survey I conducted in the Dead Sea region, I found that some species growing in certain places contain tiny amounts of gold, with no benefit to the plant, and unfortunately, no real economic value either.

Plants and Salts

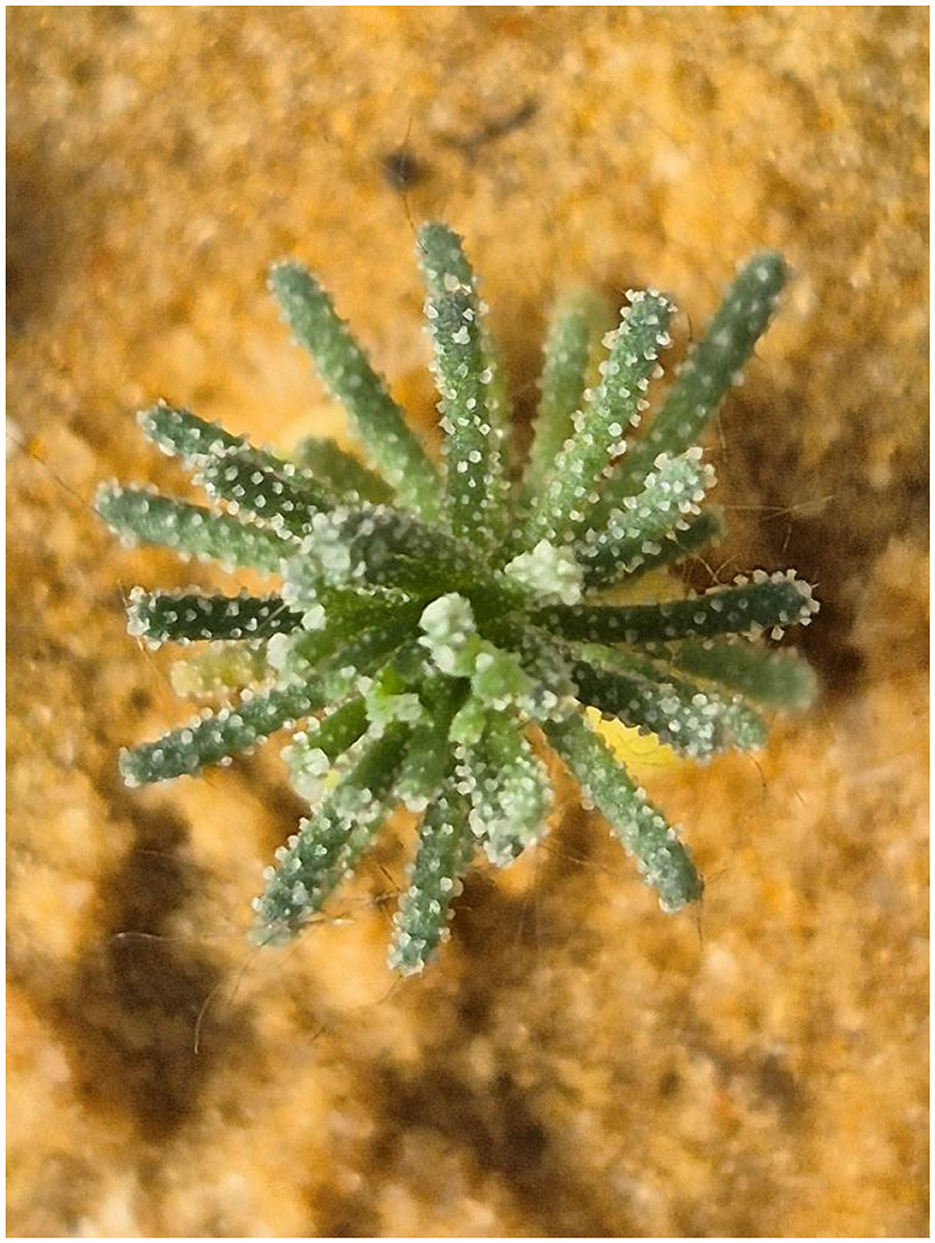

But of course, chemical elements that do nothing are pretty dull. The interesting elements can be roughly divided into two groups, “good” and “bad”, from the plant’s point of view. Let us start with the harmful elements that disrupt the plant’s regular activity. One of these elements is sodium. When there is too much sodium in a plant, it impairs the movement of fluids in it. Why? Because water always flows in the direction where it can “dilute” (or water down) high concentrations of salts, but from the plant’s point of view, this is not always the desired direction. Several plant species that are typical of deserts and high-salinity habitats have learned to deal with this problem. They trap sodium in salt crystals (like salt that we sprinkle on our food) so that the sodium does not dissolve and react chemically. Some plants excrete this salt from their bodies (Figure 1). These salt crystals, a marvel of nature, not only prevent excess sodium from dissolving in the plant—they can also protect the plant from herbivorous animals, which usually prefer food without large salt crystals that can scratch them or get stuck in their throats. Even viruses can have trouble getting into such a plant.

- Figure 1 - Salt crystals on a Reaumuria hirtella.

- Reaumuria hirtella plants form salt crystals (sodium chloride) in special glands and secrete them from their bodies to get rid of excess sodium and to protect themselves from animals and viruses (Photo credit: Yuval Gedulter).

Similarly, trees that grow in environments with very salty groundwater can be exposed to large amounts of sulfur. Sulfur is an essential element for plants, but like everything else, it is harmful in high concentrations. Trees like the tamarisk (salt cedar) have a unique way of dealing with this. They can concentrate the sulfur in small spaces where there is a high concentration of calcium. When the two elements are mixed in high concentrations, they crystallize in the form of gypsum or gypsum-like materials. To give you an idea of how significant this phenomenon can be, it is not rare to find tamarisk trees that have a quarter or a third of their trunks made of gypsum or a similar material!

Glass Plants?

The element closest to my heart is silicon. In many plants, especially those in the Gramineae family (such as wheat and barley) and their relatives, silicon accumulates inside the plant’s cells and on its surface, in a chemical structure that is very similar to that of glass, but very small, at most a few dozen micrometers in size. In the spring, when the wind blows, the leaves of wheat moving in the field sparkle, thanks in part to that microscopic glass that reflects light at different angles.

Silicon has many functions in plants [2]: it binds to several harmful elements, such as those I described earlier, and prevents them from reacting with other substances in the plant. Because it accumulates in thin layers that resemble glass, silicon creates an effective physical barrier. It prevents bacteria and fungi from penetrating into the plant, and it reduces water loss by limiting the amount of water that leaves through the stomata. Silicon can even be found inside the cells that control the opening and closing of the stomata, giving the plant better control over these structures.

The microscopic glass also helps the plant protect itself from herbivorous animals [3]. If you are a small insect, even a tiny piece of glass can scratch the soft tissues of your mouth and digestive tract, and possibly even block them. Because the glass surrounds some of the cells, it also makes it difficult to crack the cells open, thus preventing the animal from extracting all the nutritious organic compounds inside the cells. In large quantities, silicon burdens the animal’s digestive system, taking up space that could be filled with nutrients (in cereal grasses, silicon can constitute more than one percent of the plant’s mass). Silicon can also help reduce the effects of different kinds of stress on plants, such as dryness and salinity, or stress caused by bacteria and other disease-causing organisms.

In a recent study I conducted with researchers in Germany (DFG grant no. SCHA 1822/19-1) (Figure 2), we grew Mediterranean needle grass, either with fertilizer that contained silicon or fertilizer without silicon. Then we exposed the grass to a species of locust. We found that exposure to the silicon-rich grain caused the female locusts to become shorter, even though there was no difference in their body weight. This result shows that silicon impairs the elongation process of females. This means that their bodies were more compact and had less volume for all their internal systems. But with all the silicon in their food, it was hard to believe that it was the digestive system that was shrinking. A likely possibility (that we did not test) is that the reproductive system needed to become more compact, which may mean that the locusts can lay fewer eggs. Therefore, the use of silicon could help reduce locust outbreaks. In males, we did not find a similar occurrence. This reinforces the possibility that silicon affects biological processes that are characteristic of the female body, such as reproduction.

- Figure 2 - Science in action.

- Taking measurements during the locust experiment (Image used with permission from Tovale Solomon and Yaron Nitka-Nakash; Photo credit: Tovale Solomon).

The Chemical Signature of Desert Plants

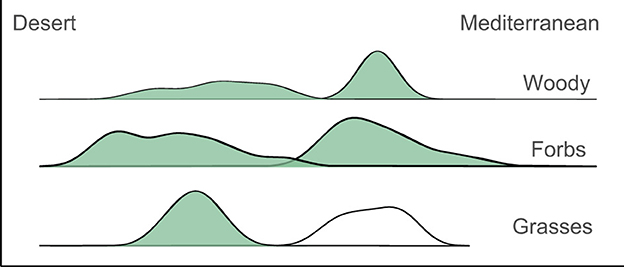

In a study that we recently published collaborating with Prof. Marcelo Sternberg and Prof. Michal Gruntman from Tel Aviv University and funded by the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 1041/19) [4], we measured the concentrations of several chemical elements in a wide variety of plants from all over Israel. One of the interesting results was that there were clear differences in the chemical composition of plants from the desert region compared to plants from the Mediterranean region (Figure 3).

- Figure 3 - Our study found a clear difference between the chemical signature of desert plants vs.

- those from the Mediterranean region. On the left are the desert plants, and on the right are the plants from the Mediterranean region. The high points represent regions where there are many species with a similar chemical signature. You can see that for each type of plant—woody, forbs, and grasses—there are two curves with almost no overlap, meaning their chemical composition is very different, and it is easy to identify whether a plant comes from the desert or the Mediterranean region by its chemistry, just as people have unique signatures.

One of the chemical elements that contributes most to the unique chemical signature of desert plants is strontium. Its concentration in plants is relatively low, but seven times higher in desert plants than in plants from the Mediterranean region. Until a few years ago, the accepted view was that strontium played no role in plants. In recent years, several studies have been conducted on individual species showing that strontium can help plants under stress. The contribution of our research is that, thanks to studying the differences between 89 plant species from two geographical regions, we can now confidently say that increased absorption of strontium is an adaptation to stress conditions in a wide range of species.

But the fundamental importance of this discovery lies elsewhere. Strontium has a radioactive isotope, which is very common in soils around sites where nuclear leaks have occurred, or in places where fuel for nuclear reactors is mined. Because the atomic structure of strontium resembles that of calcium, plants and animals sometimes “confuse” the two elements, and thus a small portion of the calcium in the body is “replaced” by strontium. Suppose the soil on which the plants grow is contaminated with radioactive strontium. It could enter the human body and cause various health issues (e.g., cancer), partly because we have a lot of calcium in our bodies (mainly in our bones). One method of cleaning up soils contaminated with radioactive strontium is to grow plants that can absorb relatively large amounts of this element, then harvest them and dispose of the radioactive material safely. Now that we understand that strontium is more common in desert plants and under stressful conditions, we can improve methods for cleaning up soil by selecting more suitable plants (such as desert plants) and further increasing the rate of strontium absorption by exposing those plants to stress. The challenge is to identify the correct plant species and the exact concentrations to achieve optimal strontium absorption.

As you can see, plants are more than they seem, and their chemistry is not limited to organic compounds. For many of the chemical elements, we are just scratching the surface, and novel revelations—such as that of the strontium—probably await us.

Glossary

Organic Compound: ↑ A chemical compound of one or more carbon atoms chemically bonded to hydrogen, oxygen, or nitrogen. Organic compounds are the chemical basis of all life.

Stomata (singular: Stomate): ↑ Openings in the outer tissue of a plant that allow gases to enter and exit. A stoma has a complex structure that controls its opening and closing.

Periodic Table: ↑ A method for classifying all chemical elements according to their chemical properties and atomic structure. We use it figuratively to describe the types and kinds of chemical elements in plants.

Salinity: ↑ High concentrations of the element sodium, or some other elements, which gives materials a salty taste and interrupts some bodily functions.

Herbivorous: ↑ Plant-eating, usually referring to eating leaves and stems (as opposed to fruits and seeds).

Gypsum: ↑ A mineral made up of calcium, sulfur and oxygen. It is often used to make drywalls and plaster (as the one used in orthopedic casts).

Micrometer: ↑ A unit of measurement equal to one millionth of a meter, or one thousandth of a millimeter. The thickness of an onion peel, for example, is about 40 micrometers.

Stress: ↑ A condition resulting from harsh conditions that impair the ability of an organism to function correctly.

Radioactive Isotope: ↑ A form of an element’s atom that is unstable. It slowly changes into a stable form by releasing energy and tiny particles called radiation.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Original Source Article

↑Katz, O., Moura, R. F., Gruntman, M., and Sternberg, M. 2025. The plant ionome as a functional trait: variation across bioclimatic regions and functional groups. Physiol. Plant. 177:e70076. doi: 10.1111/ppl.70076

References

[1] ↑ Kaspari, M. 2021. The invisible hand of the periodic table: how micronutrients shape ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 52:199–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-012021-090118

[2] ↑ Katz, O. 2019. Silicon content is a plant functional trait: implications in a changing world. Flora 254:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2018.08.007

[3] ↑ Johnson, S. N., Hartley, S. E., and Moore, B. D. 2021. Silicon defence in plants: does herbivore identity matter? Trends Plant Sci. 26:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2020.10.005

[4] ↑ Katz, O., Moura, R. F., Gruntman, M., and Sternberg, M. 2025. The plant ionome as a functional trait: variation across bioclimatic regions and functional groups. Physiol. Plant. 177:e70076. doi: 10.1111/ppl.70076