Abstract

From their adorable name to their leading role in the movie Finding Nemo, many people find clownfish, also called anemonefish, cute and lovable. Clownfish must live in animals called sea anemones to survive on a coral reef. For 19 years, we followed two-banded anemonefish off the coast of Israel in the Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba), Red Sea. Based on their size, we divided the fish into adults, teens, and babies. In 1997, 195 fish of all ages lived at the site. By 2015, 52 fish—mostly adults—remained, a 74% drop. From 1997 to 2015, the number of sea anemones also fell from 199 to only 27, and each one was more crowded with anemonefish. Climate change may affect sea anemone survival. Without their sea anemone homes, clownfish cannot exist, raising concerns about their future.

In the Wild, Clownfish Must Live in Sea Anemones

When you play musical chairs, there is one less chair than players. When the music starts, the players walk around the chairs. When the music stops, each player scrambles to sit on a chair. The person left without a chair is eliminated. One chair is removed, and the game continues until one chair, and one person sitting on that chair, remains. This person wins the game. Musical chairs would not be a game of elimination if everyone had their own chair, or if there were more chairs than people. Clownfish, also called anemonefish, must have a “chair”, a sea anemone, to survive in the wild (Figure 1). As long as there are enough sea anemones, clownfish babies, teens, and adults, have homes. If sea anemones die as a result of climate change, clownfish numbers will crash.

- Figure 1 - Clownfish musical chairs.

- In the wild, clownfish cannot survive without a sea anemone. Similar to the game musical chairs, when there are not enough sea anemones on a coral reef, baby clownfish cannot join the clownfish community. Teen and adult clownfish without an anemone may die.

Sea anemones are invertebrates that belong to the same phylum as corals and jellyfish. Sea anemones look sort of like a plastic/latex glove. If you fill up a glove with water, the water-filled fingers are like the tentacles of a sea anemone, except sea anemones have many tentacles. The only opening into the sea anemone is in the middle of the “glove”. This opening allows food to come into the anemone’s body and waste to leave. Like corals, sea anemones have algae that live within them, and both the sea anemone and the algae benefit from the relationship. When individuals from different species live together in this way, it is called a symbiosis [1]. When the symbiosis is beneficial to both of the individuals, it is called mutualism [1]. The clownfish-sea anemone relationship is a mutualistic one. Without a sea anemone, clownfish cannot survive in the wild because they will be eaten by predators. Sea anemones with clownfish benefit by growing faster and surviving better than sea anemones without fish [2]. Climate change can lead to conditions that may harm corals and sea anemones, as well as the organisms that live within the coral/sea anemone body, such as the algae, or fishes that live within coral branches or the clownfish that live amidst sea anemone tentacles [3, 4].

Studying a Clownfish Community in the Red Sea

Nearly 30 years ago, we started studying clownfish in the Gulf of Eilat, in the Red Sea. The two-banded clownfish (Figure 2A) is the only clownfish found in the Red Sea. In the Gulf of Eilat, the two-banded clownfish lives in either the bubble-tip anemone or the long-tentacle anemone (Figure 2B). To learn about the clownfish community, we first needed to map out an area of the coral reef. To do so, we went SCUBA diving, placing measuring tapes on the sea floor to determine the length and width of the area that we would study. Once we had the edges of the area mapped out, we marked the location of every sea anemone on a map, whether it had fish or not, and whether the fish were adults, teens, or babies. For the first year of the study, we checked on the clownfish community every month, which allowed us to answer several scientific questions. For example, we found out that adult clownfish live mostly in the bubble-tip anemone, surviving better there than in the long-tentacle anemone [4]. Babies, probably because of their small size, survived equally well in both sea anemone species.

![Figure 2 - The two-banded clownfish and the two types of sea anemones, the bubble-tip anemone [bottom of (A)] and the long-tentacle anemone (B) that two-banded clownfish call home in the Gulf of Eilat (photos by DG).](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1373561/frym-12-1373561-HTML/image_m/figure-2.jpg)

- Figure 2 - The two-banded clownfish and the two types of sea anemones, the bubble-tip anemone [bottom of (A)] and the long-tentacle anemone (B) that two-banded clownfish call home in the Gulf of Eilat (photos by DG).

When Do Clownfish Babies Join a Clownfish Community?

Clownfish babies hatch from fertilized eggs attached close to the bottom of the sea anemone where the parents live. Since sea anemone tentacles sting, the eggs’ location provides protection. When the babies hatch, they go up into the sea water, where currents may carry them away from the reef from which they came, to another reef. Or, the babies may stay in the water close to home, and eventually find an anemone “chair” and settle down on the same reef. In our study, we found that clownfish babies joined the clownfish community mostly in the months of October, November, and December [4], although we do not know if the babies that settled came from afar or from nearby.

How is the Clownfish Community Spread Out on the Reef?

Counting clownfish, putting them into age categories, and counting sea anemones in the study area are important for understanding the clownfish community. But looking only at numbers does not uncover the entire story. One thing that we did in our study that was different from other studies is that we also recorded where the clownfish and sea anemones were found on the reef. By collecting this information, we found out that adult clownfish protect not only the sea anemone in which they live, but they also prevent other clownfish from living in nearby sea anemones [4]. It is like playing musical chairs but a player sitting on a chair not only prevents other players from sitting on their chair, but also on the empty chairs immediately nearby. As a result, even if there are empty chairs (sea anemones), babies cannot settle into them and teens cannot move to them without fighting the adult clownfish—a fight that the smaller fish may not win.

Findings From 20 Years of Observations

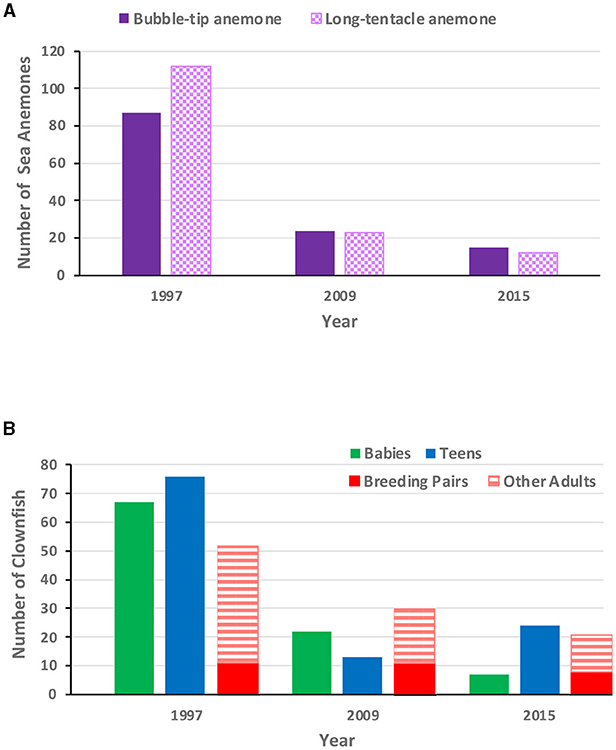

In 1997, 195 clownfish lived in 199 sea anemones (Figure 3A). The 195-clownfish community included 52 adults, 76 teens, and 67 babies (Figure 3B). A male and female adult clownfish that live in the same sea anemone are called a breeding pair (parents). In 1997, out of the 52 adults, 22 adults formed 11 breeding pairs (Figure 3B) [4]. By 2009, the picture on the reef completely changed. Only 47 anemones occurred at the study site (Figure 3A) [4]. That means that only a quarter of the sea anemones were left! Not surprisingly, with fewer sea anemone homes, the clownfish numbers also fell, with only 65 fish, roughly one third of the starting number, remaining in the study area (Figure 3B).

- Figure 3 - (A) The number of sea anemones and (B) clownfish at the coral reef study site in 1997, 2009, and 2015.

- From 1997 to 2015, the total number of sea anemones fell from 199 to 27. The total clownfish numbers also dropped from 195 to 52. Between 1997 and 2015, fewer adults remained, but the number of breeding pairs only dropped slightly, from 11 to 8. The big change was in the number of babies in the community, falling from 67 in 1997 to only 7 in 2015.

Six years later, in 2015, fewer sea anemones remained—only 27 (Figure 3A). In these sea anemones lived 52 clownfish [4]. So, the anemone numbers fell from 47 in 2009 to 27 in 2015, a loss of nearly half of the sea anemones. The clownfish numbers also dropped, but not by as much—only 20%—with clownfish numbers falling from 65 to 52 fish (Figure 3B). With half of the sea anemone “chairs” gone, the remaining clownfish crowded into the few sea anemones left, resulting in more clownfish in each anemone.

Counting clownfish provides important information but does not differentiate the ages of the clownfish in the community. In 1997, adults accounted for only a quarter of the clownfish community. That meant that teen and baby clownfish outnumbered the adult clownfish (Figure 3B). By 2009, adults made up nearly half of all the fish in the smaller fish community, although the number of breeding pairs stayed the same (Figure 3B). In 2015, adults continued to be a bigger part of the community than they were in 1997 [4]. What was very concerning was that, in 2015, there were only seven babies in the community (Figure 3B). With all the sea anemones occupied, babies might not find a sea anemone home to move into. If there are fewer and fewer sea anemone “chairs”, and babies cannot join the clownfish community, eventually the clownfish community may collapse.

In 2003, the lovable animated clownfish, Nemo, starred in the blockbuster film Finding Nemo. In 2016, the sequel Finding Dory hit movie theaters. If the clownfish community that we followed in the Gulf of Eilat continues to decline, the third movie in the series may be What Is a Nemo? We hope our continuing research will lead to a different movie title, with this lovable mutualism continuing to survive on coral reefs.

Glossary

Invertebrates: ↑ Animals without backbones.

Phylum: ↑ A category used for organizing organisms. Humans, for example, are in the phylum Chordata.

Symbiosis: ↑ When individuals from different species live together.

Mutualism: ↑ A type of symbiosis in which both partners benefit from the relationship.

SCUBA: ↑ An acronym for self-contained underwater breathing apparatus. SCUBA equipment provides the oxygen needed to go underwater and be at eye level with the fish in the sea.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Howell, J., Goulet, T. L., Goulet, D. 2016. Anemonefish musical chairs and the plight of the two-band anemonefish, Amphiprion bicinctus. Environ. Biol. Fish. 99, 873–86. doi: 10.1007/s10641-016-0530-9

References

[1] ↑ Goulet, T., and Goulet, D. 2021. Climate change leads to a reduction in symbiotic derived cnidarian biodiversity on coral reefs. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:636279. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.636279

[2] ↑ Holbrook, S. J., Schmitt, R. J. 2005. Growth, reproduction and survival of a tropical sea anemone (Actiniaria): benefits of hosting anemonefish. Coral Reefs 24:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s00338-004-0432-8

[3] ↑ Liberman, T., Genin, A., and Loya, Y. 1995. Effects on growth and reproduction of the coral Stylophora pistillata by the mutualistic damselfish Dascyllus marginatus. Mar. Biol. 121:741–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00349310

[4] ↑ Howell, J., Goulet, T. L., and Goulet, D. 2016. Anemonefish musical chairs and the plight of the two-band anemonefish, Amphiprion bicinctus. Environ. Biol. Fish. 99:873–86. doi: 10.1007/s10641-016-0530-9