Abstract

Biodiversity is the word used to describe the rich variety of life on Earth. Right now, Earth’s biodiversity is threatened. Museums, zoos, and other kinds of natural history collections help to protect biodiversity. One way they do this is by helping researchers study life on Earth. Another way is by teaching people, through exhibits and events. Natural history collections face many challenges. One challenge is getting enough money to stay open. Another is finding new space as collections grow. Finally, some people who want to use and learn from collections cannot access them because they are not nearby. Museum collections are now putting information on the internet, so that many people can access and use it. We can all help natural history collections to continue protecting Earth’s biodiversity by visiting them, volunteering, and donating specimens or other resources.

What Is a Natural History Collection?

When was the last time you visited a museum or a zoo? As well as being interesting and fun to visit, the collections that zoos and museums preserve also help to protect Earth’s biodiversity. Generally, biodiversity means the variety of life on Earth, which includes plants, animals, fungi, and even bacteria. Biodiversity is important because all organisms have a right to exist. Also, biodiverse environments provide services to humans, like foods, medicines, and natural beauty. Right now, biodiversity is facing many threats, including habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change. These threats cause organisms to become rare or even extinct.

Natural history collections are places that bring together, protect, and study specimens. Specimens contain two kinds of information. The first type of information is the physical object itself, like a beetle, bird, plant, fossil, or rock (Figure 1). The second kind of information that a specimen gives us is information about that object, like when and where the specimen was found. This information is usually written on a specimen label, so it is called label data. You might think label data are less important than the physical object, but that is actually not true! To connect the specimen back to the world, we must know when and where it came from.

- Figure 1 - (A) Bird, (B) beetle, and (C) butterfly specimens from the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates and the Cornell University Insect Collection.

- Specimens like these are used by scientists from around the world to study and protect biodiversity. (D) A pinned insect specimen, with its label, which tells scientists that it was collected in Gainesville, Alachua County, Florida, on April 28, 1971, by F. W. Mead, using a blacklight trap.

Some natural history collections are in museums. Many are at colleges and universities. There are also some types of natural history collections that you might not think of at first. For example, seed banks are large collections of plant seeds that are kept safe for the future. Also, aquariums, botanical gardens, and even zoos are all collections! They are simply collections made of still-living things. Large natural history collections might bring together many types of specimens, like fossils, pinned insects, and living butterflies—all under one roof!

Biodiversity Research in Natural History Collections

Scientists use specimens plus the information on labels to understand the world around us in many creative ways. Some collections have very old specimens, like fossils that are millions of years old, or birds from hundreds of years ago. These specimens let scientists “time travel,” to see what organisms looked like in the past, where they were found, and how they might have changed over time. This information can be used to protect the biodiversity that is alive today. For example, scientists used natural history collections of Canadian butterflies to see where the butterflies live—their habitats [1]. Butterfly habitats include the plants these butterflies eat and their preferred climate conditions. Because of climate change, the places where a butterfly’s preferred habitat can be found have changed over time. So, scientists checked to see if the butterflies are moving, too. They found that some butterflies are not moving to follow their habitats, which puts them at risk of going extinct. People can use this information to decide how to protect these butterflies from extinction in the future.

In the past 20 years, we have started using a new kind of information from natural history collections: DNA! DNA is found inside all living things, where it is the “code” or instruction manual for building the organism. To collect DNA, scientists treat specimens with chemicals that dissolve the DNA while leaving other parts of the specimen intact. Then, they can read the DNA code and use it to better understand biodiversity. DNA is still present even after organisms die, so specimens in natural history collections are full of DNA! Some special collections, like the Frozen Zoo at the San Diego Zoo, are specifically used to store frozen DNA.

How does information from DNA help to protect biodiversity? Well, natural history collections are the only way to study the DNA of extinct organisms! This can provide clues about why the organism went extinct. Scientists can also use DNA to understand living organisms. For example, animals from two separate places can look very similar, but their DNA can be so different that they are actually different species. This means we should protect both groups of animals, not just one or the other. Scientists have done this for the endangered Chinese giant salamander [2]. Using DNA from collections, they found that the giant salamander is actually three separate species! All three species must be protected.

Aquariums, botanical gardens, and zoos are special collections, full of living specimens. They play a unique role in conserving biodiversity. Zoos protect biodiversity through captive breeding programs, in which researchers keep endangered animals safe in the zoo so they can have babies. Once the baby animals grow up, they are returned to the wild. This helps wild animal populations grow and avoid becoming extinct.

Facing the Public: Displays and Beyond

People visit natural history collections for many reasons. Some people visit to relax, others because it is an exciting activity. Many people visit because they are curious and want to learn. Collections are best known for their cool exhibits and events. Exhibits are one great way that collections use specimens for public viewing. These displays are changed from time to time, to highlight different specimens. Exhibits show us where specimens come from, like oceans or forests (Figure 2). Many collections also have events, like fairs that show off colorful bugs or furs from big cats. Events like stargazing and nature walks are fun to do, and they are educational! For those who want to learn even more, many natural history collections offer classes and other programs, for example, teaching how to prepare and care for specimens.

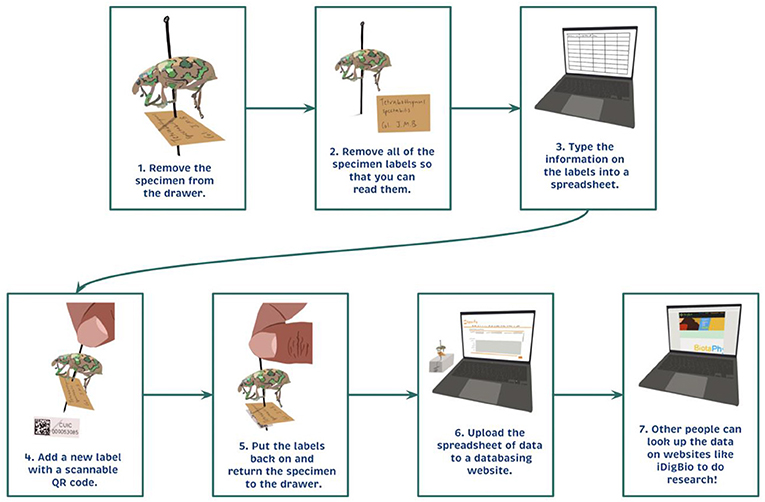

- Figure 2 - Flowchart shows how to digitize the data from a natural history collection specimen.

- First, a specimen is removed from its drawer, and then the labels are removed to read them. Next, all the label data are typed into a spreadsheet. A new label with a scannable QR code is added to the specimen; this lets other researchers scan the specimen to look it up. Then the specimen is put away. Finally, all the information is uploaded to a databasing website, where other people can find and use it!

Zoos might be the best way for collections to engage with the public! Zoos are exciting because you can make eye contact with an animal or feel a plant’s soft leaves. Visitors can learn about the varieties of plants and animals by being up close with them. For example, the San Diego Zoo has a park that feels like a real African safari. Zoo visits can be fantastic ways to learn about biodiversity. When people learn about something and interact with it, they may start to care more about biodiversity and the natural world.

The Future of Natural History Collections

Just like biodiversity, natural history collections face many challenges. One big challenge is money. Collections need money to care for their specimens. They must also pay their workers, and they need money for research. Money usually comes from the government, universities, admission fees, or donations. Often, natural history collections do not have enough money to do all the things they want to do. Sometimes, collections must even close, giving their specimens to larger museums, because of a lack of money.

Collections are always growing, so space is another issue. There are many ways to fit as many specimens as possible into a collection. For example, collections use cabinets on wheels, which can be pushed together with no space in between them—that helps scientists fit more cabinets in a room! Then, workers can roll out just one cabinet at a time when they need to use it. Still, collections eventually need new rooms and buildings.

Another challenge is making information from natural history collections available to everyone. Collections do this by digitizing, which means putting information about specimens online. This takes lots of work (Figure 2). Specimens must be photographed, label data must be typed up, and all the information must be put online. Some collections have hundreds of millions of specimens. Digitizing all those specimens is a huge task! But it is important, because it allows people from around the world to use the collection, not just people who can visit in person. One cool digitization project is oBird, which creates 3D images of bird specimens [3].

Finally, it is important for natural history collections to keep growing. We use collections to know what the biodiversity of the planet looked like long ago. Future researchers will need specimens from today to know what biodiversity was like right now! Scientists and community members should keep giving specimens to collections, so they can be protected and studied in the future.

What Can You Do?

If you want to help preserve these collections, first find out where your local natural history collection is! It might be a big museum like the Chicago Field Museum, or a small collection at a local university. Many collections love having visitors. So, reach out and ask for a tour or how you can volunteer. Right now, many collections are working hard to put years and years of information online. This can be anything from photos of specimens to typing up the location on the labels. You can volunteer to help through websites like iDigBio and DigiVol!

Collections want to help protect biodiversity. If you have specimens you can donate, this is a fantastic way to support them. Collections take in new specimens all the time. They want to know where and when the specimens came from (Figure 3). These data are part of a treasure trove of information about the specimen. Is it a cool bug? A bird that hit a window? A rare plant in your backyard? They want every detail. We can all help keep these cool collections growing!

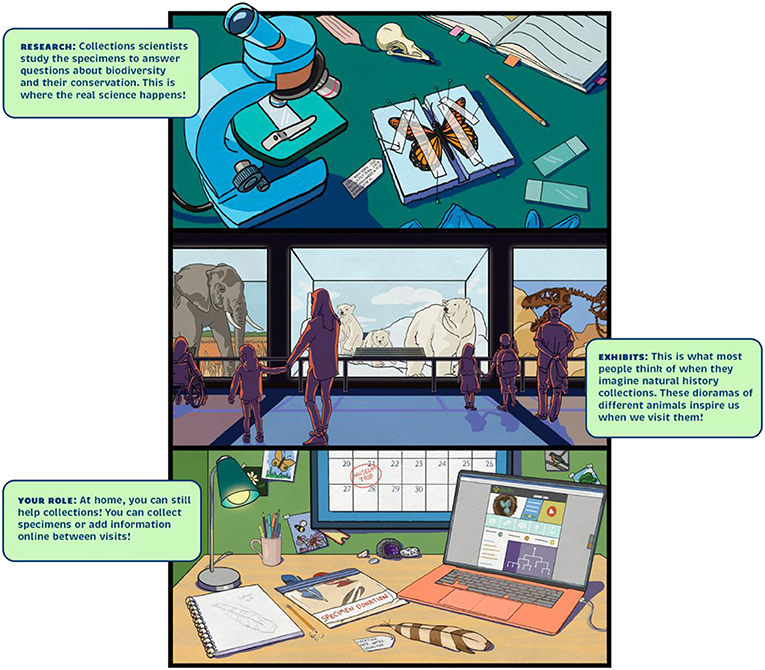

- Figure 3 - Three distinct aspects of natural history collections.

- First, scientists use natural history collections to help with research. Second, the public interacts with natural history collections through museum exhibits, to learn more about biodiversity. Third, you can help collections yourself, by collecting and donating specimens, or volunteering online (Figure credit: Charlotte Welker Holden)!

Glossary

Biodiversity: ↑ The variety of life on Earth, including plants, animals, fungi, and bacteria.

Natural History Collections: ↑ Places that bring together, protect, and study specimens from the natural world.

Specimen: ↑ A physical object stored in a natural history collection.

Label Data: ↑ The information about a specimen that is recorded on its label, including data like when and where the specimen was collected.

Habitat: ↑ The natural home of an animal, plant, or other living thing.

Extinct: ↑ When a species or group of organisms has no living members and no longer exists on the planet.

Digitizing: ↑ Gathering information about specimens and putting it into computers. This can include what is written on the specimen’s label or even pictures or 3D scans of the specimen.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jason Dombroskie, CUIC Collection Manager; Mary Margaret Ferraro, CUMV Bird Collections Manager; and Charlotte Welker Holden, Cornell Lab of Ornithology Bartels Science Illustrator. We also thank our Young Reviewers and their Science Mentors for constructive feedback on this manuscript. This material was supported by the National Science Foundation (DBI 2210800) to CSM, the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-2139899 to MB, and the Ford Foundation Pre-doctoral Fellowship and Alfred P. Sloan Foundation’s Minority Ph.D. Program under Grant No. G-2019-11435 to MP. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

References

[1] ↑ Lewthwaite, J. M. M., Angert, A. L., Kembel, S. W., Goring, S. J., Davies, T. J., Mooers, A. Ø., et al. 2018. Canadian butterfly climate debt is significant and correlated with range size. Ecography 41:2005–15. doi: 10.1111/ecog.03534

[2] ↑ Turvey, S. T., Marr, M. M., Barnes, I., Brace, S., Tapley, B., Murphy, R. W., et al. 2019. Historical museum collections clarify the evolutionary history of cryptic species radiation in the world’s largest amphibians. Ecol. Evol. 9:10070–84. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5257

[3] ↑ Medina, J. J., Maley J. M., Sannapareddy, S., Medina, N. N., Gilman, C. M., and McCormack, J. E. 2020. A rapid and cost-effective pipeline for digitization of museum specimens with 3D photogrammetry. PLoS ONE 15:e0236417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236417