Abstract

When people must share things, what does it mean to share fairly? Do all people around the world have the same idea of what is fair or unfair? Are humans born with a feeling about what is fair and unfair, or is it something we learn as we grow up? Scientists study how people from different cultures choose to share things in various situations, and whether people think different ways of sharing are fair or unfair. This article describes an experiment in which scientists studied whether children from different cultures have different ideas about what is fair. These studies are important for understanding how humans are similar and different from each other and from other animals, and they also help us understand how we can work to create a world that is considered fair by everyone.

Fairness Does Not Mean the Same Thing to Everyone

Imagine this situation: Ana, Ben, and Carla baked a cake together and are now discussing how to split it. Ana says it is only fair to split the cake into equal amounts so that everyone gets exactly one third. Ben says he should get more than the other two because he did most of the baking. Carla says she needs more cake than the others because she has a little brother with whom she must share her piece of cake, while the other two have no siblings. All three get into an argument about what is fair, each one with their own understanding.

Can you remember a similar situation in your own life when you felt that you were treated unfairly? We humans seem to care a lot about fairness, and we all know what it is like to feel unfairly treated—it makes us angry and frustrated. Therefore, many scientists are trying to understand fairness. Some scientists study the brain to understand how the brain makes us care about being treated fairly. It turns out that the same areas in the brain that make us feel angry, sad, scared, or happy also create our sense of fairness—this means our sense of fairness is a very emotional reaction.

Other scientists are interested in how humans behave, what they do, and how they think about things like fairness. These scientists have found that people seem to have different views on how resources (like food or money) should be fairly shared in a group, which is why we often get into arguments with other people about what is fair. There are three main ways of sharing resources. The first is called equality, in which everybody gets the same. Sharing resources can also be based on equity, in which people who worked harder or contributed more also get more. Last, resources can be shared according to need-based sharing, in which people who need more, also get more. Can you tell which participants in the cake story above seem to have these different views on how to share resources? Which ideas of fairness did Ana, Ben, and Carla follow?

Why do different ideas about fairness exist? If all humans care so much about fairness, why don’t we all have the same understanding of what fair means in a situation? One factor that could make us disagree about what is fair is our own role in the situation. For example, could it be that in our cake scenario, Ana considers the idea of equality to be fair only because she can get cake even if she did not do much work? Could it be that Ben just considers equity to be fair because he was the one who did most of the work? Could it be that Carla considers need-based sharing to be fair because she is the one who must share with her brother? Another factor causing disagreement could be our beliefs about other people’s efforts and intentions. Would Ben think differently if he knew that Ana and Carla wanted to help him more, but were not able to for some reason?

We might also disagree about what is fair based on what we learn about fairness as we grow up. For example, in some places or cultures, children may learn that it is very important to pay attention to who has done the work when deciding how much to share. In other places, children may be taught to think more about others’ needs. Could it be that people have different ideas about fairness in the same situation because they grew up in different places and cultures, and thus learned different ideas from their parents and other people around them?

How Did We Study Cultural Ideas About Fairness?

To better understand the role of culture in our ideas of fairness, scientists often study how children and adults develop a sense of fairness during childhood, and how adults and children from different cultures think about fairness in various situations.

In one study [1], scientists conducted an experiment with 4- to 11-year-old children from two different cultures. One group of children came from a city in a Western country (Germany). Another group of children came from a hunter-gatherer society, the Haikom (pronounced with a clicking sound) in Namibia. In Haikom society, people mostly obtain their food by hunting wild animals and gathering wild plants. In the experiment, the scientists grouped the children into pairs. There were about 25 pairs for each cultural group, and the children in each pair were of the same culture, of the same gender and age, and knew each other.

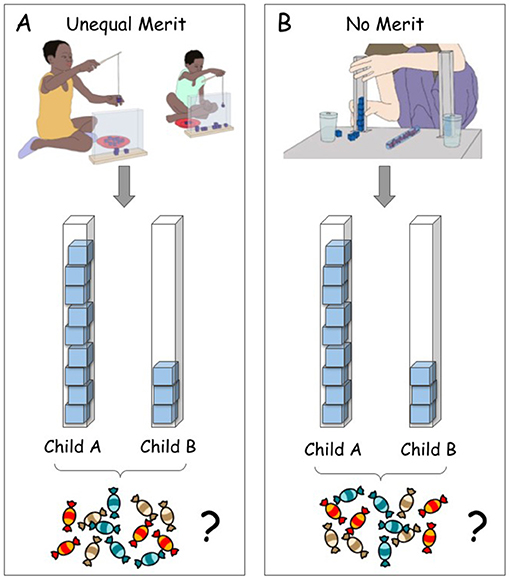

Each pair played a game that involved fishing for cubes from a water tank (Figure 1A). The cubes were magnetic, and the children fished the cubes from their tanks using magnetic fishing rods. However, the scientists used cubes that were not all magnetized equally, and the children did not know this. Only three cubes were magnetic for one child and nine cubes for the other child, so that one of the children could only fish a maximum of three cubes, and the other could fish nine. The scientists called this version of the fishing game the unequal merit game (Figure 1A). In another version of the experiment, the children did not play a real game. The scientists gave three cubes to one of the children and nine to the other, but the children did not have to do anything to get the cubes. The scientists called this version of the fishing game the no merit game (Figure 1B). After each game, the scientists gave the pairs 12 pieces of candy: one candy for each cube that they had together fished from the tanks or received from the scientist. The scientist left the two children alone with their 12 candies, without telling them how they should share the sweets. The scientists were interested to see what the children thought would be a fair way to divide the 12 candies, when no adult was involved in the decision.

- Figure 1 - Pairs of children, either from Germany or Namibia, participated in an experiment to examine differences in cultural ideas about fairness.

- (A) In the unequal merit game, not all the cubes were magnetized, so one child could fish out nine cubes, and the other only 3. (B) In the no merit game, the scientist just gave one child nine cubes and the other three. Then, in each case, the two children got twelve pieces of candy to share, with no input from adults about how to divide them.

Before you read on, try to think about how you would divide the candy and what you would consider fair in each of these two situations. Do you think the children from the different cultures might have shared differently than you would?

Differences Exist Between Cultures!

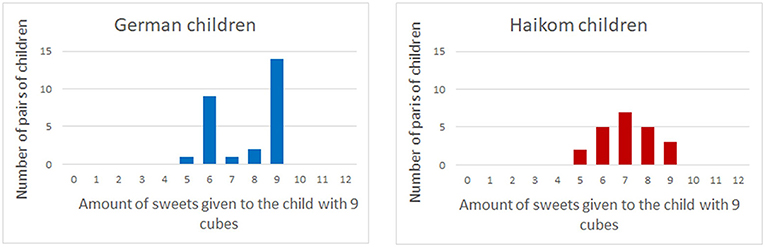

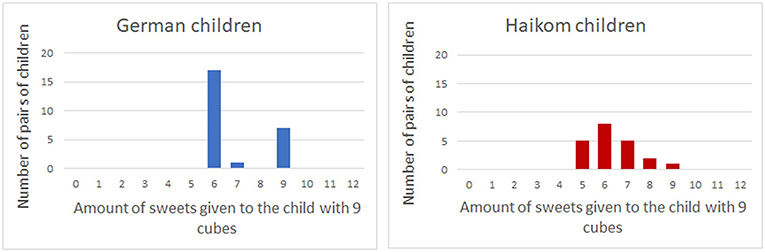

In the unequal merit game, the children of the two cultures seemed to behave differently (Figure 2). Many German children seemed to care more about equity, meaning the child who fished nine cubes also often got exactly nine candies. The children of the Haikom seemed not to care as much about who had fished more cubes and tended to divide the 12 candies rather equally. However, in the no merit game, in which the children just had been given different amounts of cubes, even the German children tended to share the candy more equally (Figure 3).

- Figure 2 - In the unequal merit game, in which one child fished three cubes and the other child fished nine cubes, the German and Haikom children shared the 12 sweets differently.

- The German children tended to share more according to the idea of equity because the child that fished nine cubes also often got nine pieces of candy. The Haikom children shared more according to the idea of equality, because they often split the 12 candy more or less equally—the child that fished nine cubes mostly got 6–8 pieces of candy.

- Figure 3 - In the no merit game, in which the scientists simply gave one child nine cubes and the other three, both the German and Haikom children tended to share the sweets more equally, with the majority of pairs giving six candies to each child.

The results of these experiments tell us that even young children from very different cultures care about what is fair when sharing with others. However, children’s sense of what is fair seems to depend on the culture they grow up in. Scientists use the term social norms for the behaviors that are typical for members of a social group and that are learned by children from other group members. For example, if children behave in a way that is considered “good” in their group, such as when they share things with others, other group members respond positively, such as with smiles and praise. When children behave in a way that is perceived as “bad” in their group, such as when they are stingy and do not want to share, other group members react negatively, such as with criticism and punishment. Through these experiences, children learn to behave in certain ways toward others. Eventually, we automatically behave according to these social norms, without thinking about it, and we get irritated or angry when we notice that other people do not behave in this way—for example, when others do not want to share in a way that we find fair.

Why Are Ideas of Fairness Different Across Cultures?

Why are social norms about fairness so different between cultures? Scientists think that this is due, at least partly, to the way that people in each culture have been living throughout history, including the types of relationships they must form with others in their community and how they organize their work in everyday life. In hunter-gatherer groups like the Haikom, people depend on hunting animals and gathering plants to stay alive, and it is important for the life of the group that everyone works together, lives in harmony with other group members, and shares food so that everyone has enough to eat. The people who interact and work together every day know each other well, so they can observe that differences in work contribution, for example when hunting or gathering food, can happen by accident or bad luck rather than out of laziness. Next time, perhaps someone else has bad luck gathering food, so the benefits for all balance out over time, and the risks are evenly distributed over the whole group. Thus, people in such groups consider it fair and right that certain resources should be shared according to the social norm of equality or need, so that everyone gets as much as needed.

On the other hand, in Western countries like Germany, individual work achievement and performance are viewed as quite important. In these societies, people meet many different people everyday, including strangers, and they often exchange money, goods, and services with people they do not know—for example, at the supermarket. This is especially true in large cities. There must be ways to manage these situations so that individuals do not take advantage of each other. After all, there may be no future encounter to make up for any inequalities. So, an equity-based norm of fairness is very important in these societies. It is considered right that people who achieve more or do a better job should also get more.

Why Does Fairness Matter?

Many problems in society have to do with people feeling that they are treated unfairly—they feel they get less money than others, or that they do not get the same opportunities and freedoms as others, or they feel that they have less power than others. When people feel they are unfairly treated, they may protest, go on strikes, or start to blame and get angry at certain groups of people. This can even lead to violence. If we could all come to an agreement on how to create a fairer society, both within our communities and between countries, the world would be a much better place for everyone to live in. Understanding where our disagreements about fairness come from is an important steppingstone toward creating a better, fairer world. We can also learn how to deal with our ideas and social norms about fairness more flexibly, and try to understand the perspectives of others, so that the interests, achievements, and unfortunate circumstances of all people are considered.

So, the next time you need to share with someone, regardless of what you are sharing, try to use these insights, see things from the other person’s perspective, and come to an agreement that takes everyone’s situation, needs, intentions, contributions, and sense of fairness into account.

Glossary

Equality: ↑ An idea of fairness that says that all members in a group should generally get the same resources and have equal status.

Equity: ↑ An idea of fairness that says that resources and power should be shared according to a person’s contribution or achievement; those who contributed more should also get more.

Need-based Sharing: ↑ An idea of fairness that says that the sharing of resources should be according to need; those who need more should also get more.

Unequal Merit Game: ↑ A version of the experiment in which one child fished out more cubes than the other child.

No-merit Game: ↑ A version of the experiment in which the children only received candy without having to do any work for it.

Social Norm: ↑ A way that most people in a group tend to behave because they learn it from others as they grow up.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑ Schäfer, M., Haun, D. B. M., and Tomasello, M. 2015. Fair is not fair everywhere. Psychol. Sci. 26:1252–60. doi: 10.1177/0956797615586188

References

[1] ↑ Schäfer, M., Haun, D. B. M., and Tomasello, M. 2015. Fair is not fair everywhere. Psychol. Sci. 26:1252–60. doi: 10.1177/0956797615586188