Abstract

Think about what is important to you in your life—think about your values! This article explains how the values of people around the world are similar and different.We present the circle of values, which shows how people around the world understand ten basic values: universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction. For a long time, scientists thought that values were an adult thing, and that children could not understand values very well. But children have values, too! The circle of values explains how our values guide us in life: We often take action for things we find important. For example, we embark on adventures if we value stimulation, but we stay safe if we value security. Finally, we will describe an experiment in which children shared chocolate coins or kept them for themselves, and we provide a link to a web page where you can test your own values.

You have probably heard the word “values”. Maybe it was mentioned by your teacher in school who spoke about what is important in class. For example, if your teacher spoke about the importance of achieving good marks, they were referring to achievement values. If your teacher said it is good to be curious and explore new ideas, they were referring to self-direction values. Maybe you have read about values in a newspaper or heard about them on TV. Politicians often talk about values in their countries, for example, about how important it is that everybody is safe (security values) and that everybody should follow rules (conformity values). Values are also part of many fairy tales, stories, and movies. Do you remember how Cinderella chose to be kind and good-hearted (benevolence values)? And did you notice how WALL-E, the last robot left on earth, worked hard to collect all the litter humans had left behind, trying to make earth a more beautiful place (universalism values)?

When we think about values, we ask ourselves: What is important to us in our lives? Some people want to become strong and powerful, maybe one day being the big boss of a company (power values). Other people find it important to have an exciting life and experience adventures (stimulation values)—these people may do crazy things like bungee-jumping. Other people follow the tradition of their family and pray to a God every day (tradition values). Finally, there are people who want to enjoy their lives, have a good time and lots of fun (hedonism values).

If we ask people around the globe what is important to them, we will get hundreds of different answers: kindness, love, freedom, success, politeness, justice, wealth, independence, and so on. We could continue this list for some time. From these many different answers, how can we understand what values exist in the world? Professor Shalom Schwartz, a scientist in psychology, has studied this question, and thousands of people from Europe, North and South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia participated.

The Circle of Values

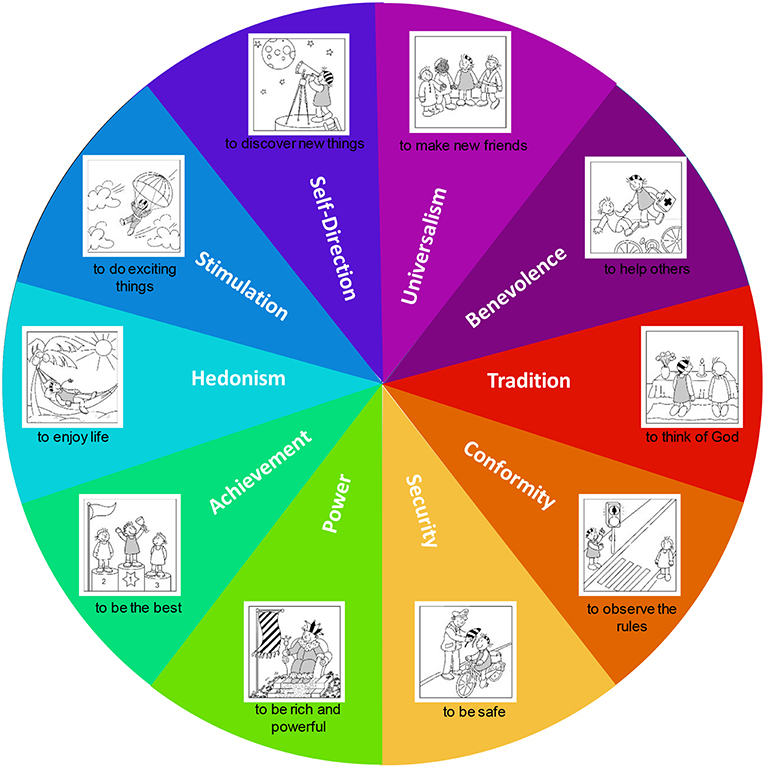

Professor Schwartz developed a circle of values [1]. This circle brought some order to the hundreds of values that are important to people. The circle also helped scientists understand how values guide us in life. You can see the circle of values in Figure 1, and you will recognize the ten values from the beginning of this article: universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction. These are called “basic values”, and people all over the world understand them. Each of the many values that exist belongs to one of the ten basic values. For example, kindness and love are benevolence values, because they are both about being good and helpful to other people around you. Curiosity and independence are self-direction values, because they are both about deciding for yourself what you want to do or learn about. In Figure 1, you can also see pictures with a title that give you more explanation about what each basic value means. These are from a values questionnaire for children. More about that later.

- Figure 1 - The circle of values.

- The circle of values shows the 10 basic values universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction. Similar values are close to each other, and conflicting values are at opposite sides of the circle. For each basic value, you can also see a picture that illustrates it. © The ideas for the value pictures were developed by Dr. Anna Döring. The pictures were drawn by Andrea Blauensteiner.

Why are the basic values shown on a circle with rainbow colors? Let’s think about how these values guide us in life. Say I find benevolence very important. That means I want to be there for my friends when they need me, help my family, and be kind to other people I know (like my classmates). Say I also find universalism important. Then I would like to make the world more beautiful for all people, I might give money to a beggar on the street, or plant trees in my neighborhood. Universalism and benevolence are similar, because both are about caring for others and the world. Therefore, they are next to each other on the circle (like two similar colors that are next to each other in the rainbow). But let’s imagine I also find power very important. I want to be rich and strong, and I want to be the leader and tell others what to do. This makes my life difficult: Do I share with others, or keep everything for myself? Do I want everybody to be equal, or do I want to be more powerful than the others? So, power values can clash with universalism and benevolence values. Because of this, they are on opposite sides of the circle. We can think about this for all other basic values, and we will always find the similar values close to each other and the values that may clash on opposite sides of the circle.

What is Important to People?

Out of the 10 basic values, which ones do people find most important? Surprisingly, people in different parts of the world are similar in that people from many countries believe benevolence is the most important—they want to care for other people, support and help those in need. Many people also find values of power—being rich and powerful and stronger than others—least important. When scientists tried to understand why humans are this way, they thought about our history millions of years back: human evolution. Humans managed to survive and develop in harsh conditions, and they were very successful. Humans invented lots of things that made their lives easier and helped them adapt to the environment they found. Working well together in a group and learning from each other was very important to achieve that. Scientists believe that this may be the starting point of today’s high importance of benevolence values.

But, you may now think, some find power more important than benevolence, and others want to have an exciting life. Yes, each person’s value priorities (how important they find each value) can be different from those of other people. Some people do want to become leaders and others want to become explorers. We can also imagine how having a leader and an explorer in the group can make the group successful.

Children’s Values

Until very recently, most scientists studied adults’ values, and a few scientists studied teenagers’ values. But what about children’s values? Do children have values, too? In 2010, Dr. Anna Döring (one of the authors of this article) developed the first values questionnaire for children between 6 and 11 years old [2], which has pictures in it. You see some of those pictures in Figure 1.

It turned out that the answer to the question is Yes—children do have values [3]. Children also think about the ten basic values from the circle of values. Of course, a child would probably not say, “self-direction is important to me”. However, a child may say that it is important to discover new things and explore the world, which is what self-direction means. When children think about their values, they think a lot about what they would do in their lives if a value was important to them. For example, children who value self-direction may think about how they want to invent new stories or go to the science museum to learn about the planets. Like adults, children can also have all ten basic values.

How do children’s values compare with adults’ values? Many children and adults worldwide find benevolence most important and power least important. Whether young or old, it is important to many people to have friends and to help and support others. But, if you look at the other values, children and adults differ. This is because values change as we grow up. For example, teenagers often become more adventurous and look for stimulation and new things to experience [3]. When teenagers become adults and start working, many try hard to do well in their jobs and be very successful. Once adults start families and have children of their own, stimulation and achievement often become less important. Professor Schwartz [4] explains that this happens because parents want to avoid risks and keep their loved ones safe and secure. Family traditions and security values hence become more important. Now think of people who grow very old. Because they are not as strong and fit as they used to be, security values may become even more important.

We have seen that our values are already present in childhood, and they accompany us through life. Values can change as we grow older and as we have new experiences [3, 4]. But for adults, who have thought a lot about their values, change is very slow and often takes many months or even years. Values express who we are as a person, what goals we have, and this does not change from one moment to the next.

How do Our Values Guide us?

Our values guide us in life. It’s not just that we talk about values, but values are our guides to actions. For example, a child who finds achievement very important will want to study a lot to get good marks in school. A child who finds universalism very important will try to protect the environment. This child may recycle, volunteer to collect litter, and grow plants.

But how do our values guide us? Lior Abramson and her colleagues [5] ran a study in Israel to find an answer to this question. The study involved 243 children between 5 and 12 years old. The children first completed the values picture questionnaire. From the children’s answers, the scientists computed a score for their prosocial values. Prosocial values are values of universalism and benevolence, which are about being kind, helpful, and supportive of others. If a child had a high score, the scientists knew that prosocial values were very important to this child. If a child had a low score, the scientists knew prosocial values were less important to this child.

Each child then played a game. In this game, the child had to share chocolate coins with another child whom he or she did not know. In Figure 2A, you can see that the child could choose between option 1 and option 2. Option 1 is selfish and option 2 is prosocial, because in option 1, the child gets more chocolate coins himself/herself than the other child. In option 2, the other child gets the same number of chocolate coins. Most children chose option 2 and shared with the other child. Here, it is easy to share, because you do not lose any chocolate yourself when you share. In option 1, there is only one chocolate coin, but in option 2, there is an additional second coin available for sharing with the other child.

- Figure 2 - The chocolate coin experiment.

- In this experiment, the player can decide how he or she would like to share chocolate coins with another child. There are two options: Option 1 and Option 2. For each option, the player gets the coins in the blue part of the picture, and the other child gets the coins in the yellow part of the picture. In (A), the player can share chocolate coins with the other child without losing coins himself/herself. In (B), the player loses a coin himself/herself if they decide to share with the other child.

In Figure 2B, the decision is more difficult. You can see that you can share with the other child. But, as it happens in real life, the same number of coins is available (in this case, two) whether you share or not. This means that you get fewer chocolate coins yourself if you share. Would children still share their chocolate if they lose chocolate themselves? Some children still shared. Who were they? Those were the children with a high score of prosocial values. The higher the children’s scores of prosocial values, the more they shared in situations like this. This means that our values guide our behavior in situations that come with some costs to ourselves. When there are no costs, most people will happily share—it is easy. But when we have to make difficult decisions, that’s when values matter.

Conclusion

We have seen that our values guide us in life, because they express what we find important. When we study values around the world, we find hundreds of them. But scientists have found that there are only ten basic values. Some of these values are about helping and supporting others, while some values are about being powerful and successful. Some values are about being safe and following rules and traditions, while other values are about experiencing adventures, having fun, and making decisions of our own. This is shown in the circle of values. Children have values too! Children can talk about what is important to them in life, and their values also guide what they do. We had a look at an experiment with chocolate coins to show this.

Find Out More About Your Values!

Now it is your turn: What are your values? What do you find important in life? What is not important to you? Test your values!

Follow the link below. This will take you to a webpage where you can test your own values.

https://hujipsych.au1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_dgU3o4Bud1neRoh

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation to AK-N (1670/13 and 1333/18). We would like to thank Louisa Gardner and Orri Knafo (young persons’ view) as well as Lior Abramson (academic’s view) for their feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript. Many thanks to the Frontiers young reviewers and their mentors, whose comments helped us a lot in further improving the manuscript. We would like to thank Guy Doytch for programming the online values survey. The research described in Figure 2 was performed at the Living Lab in Memory of Noam Knafo at the Jerusalem Bloomfield Science Museum.

References

[1] ↑ Schwartz, S. H. 1994. Are there universal aspects in the content and structure of human values? Social Issues 50:19–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01196.x

[2] ↑ Döring, A. K., Blauensteiner, A., Aryus, K., Drögekamp, L., and Bilsky, W. 2010. Assessing values at an early age: the picture-based value survey for children. J. Pers. Assess. 92:439–48. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2010.497423

[3] ↑ Döring, A. K., Daniel, E., and Knafo-Noam, A. 2016. Introduction to the special section: value development from middle childhood to early adulthood—new insights from longitudinal and genetically informed research. Social Dev. 25:471–81. doi: 10.1111/sode.12177

[4] ↑ Schwartz, S. H. (n.d.). Human Values. Retrieved from: http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/1/

[5] ↑ Abramson, L., Daniel, E., and Knafo-Noam, A. 2018. The role of personal values in children’s costly sharing and non-costly giving. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 165:117–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.03.007