Abstract

Bullying is an aggressive behavior among school-aged children. Bullying is repeated over time and includes behaviors such as hitting, breaking someone’s things, name-calling, spreading rumors, or posting someone’s private photos online. Researchers all over the world have found that children who are bullied may have serious health problems, including depression, anxiety, sadness, sleep and eating problems, and decreased performance in school. Psychological studies can help to prevent these serious problems, by analyzing which factors put a child at risk of being bullied. Using anonymous questionnaires, we asked children aged 10–12 years old to report if they were suffering some kind of bullying and how they felt about their relationships both in and out of school (for example, how easily they become friends with other children). We wondered if bullying could happen even in a circle of good friends. We can use the information learned in this study to promote prevention programs in schools, to advise children about how to deal with bullying.

What is Bullying?

The word bullying is probably familiar to you. You may have heard it on TV, read about it in a book or magazine, or heard it from a friend or someone you know. You may have even used this word to describe a situation you have seen at your school or even to describe something that might have happened to you. No doubt you already have your own definition of bullying, and you may be quite clear about what bullying is and what it is not. However, not everyone agrees when it comes to defining bullying. Even researchers who study this topic don’t always agree when they define bullying, even though research on bullying started more than 40 years ago.

However, there are some things the researchers do agree on. They agree that bullying is a form of aggression, meaning that it’s a behavior used to hurt someone. From this point of view, when someone hits or pushes someone else, insults somebody, or does not allow someone to play with his or her group of friends, we could state that this person is bullying others. Most researchers would agree that aggression must fulfill two other conditions to be considered bullying [1]: (1) repetition, meaning that the behavior must happen more than once; and (2) power imbalance, meaning that it must be difficult for the victim to defend him or herself. The power imbalance can be the result of the bully being physically stronger or more popular, or because the bully is part of a group of people who act together to pick on one individual.

Bullying includes physical behaviors (hitting, kicking, damaging a victim’s property), verbal attacks (name calling, threats), and social aggression (excluding someone from a group, rumor spreading). Bullying also includes more recent types of behavior through the Internet and other new technologies, which is called cyberbullying (posting someone’s private photos online, for example) [2].

Bullying Involves Groups of Children, Not Just a Bully and a Victim

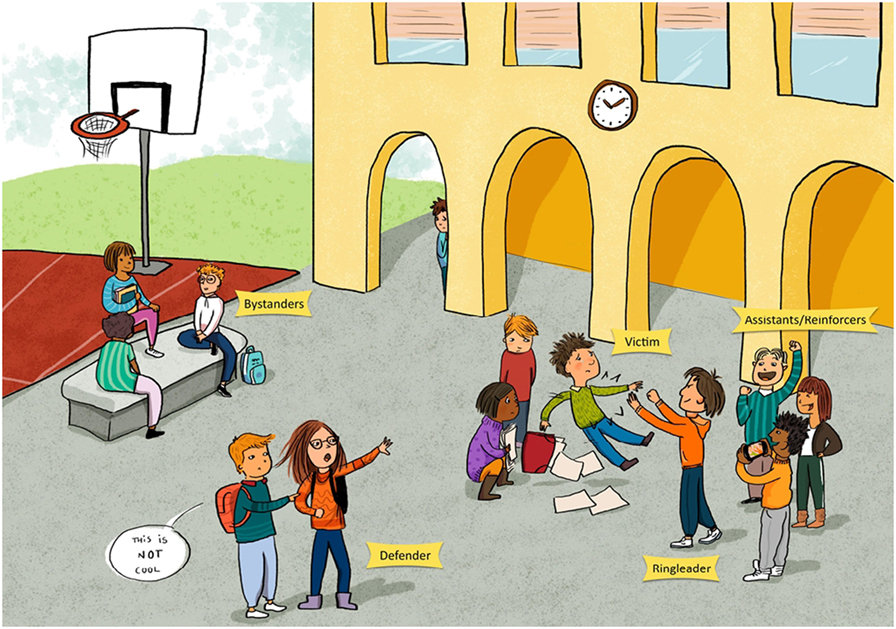

Bullying is not limited to one person who is aggressive and another person who is the victim of this aggression. Bullying is a social behavior that takes place mainly at school and involves everyone who witnesses it, even if they are not directly involved in it [3]. In Figure 1, you can see all the people involved in a bullying situation. In the bully role, we find the ringleader (the person who starts and leads bullying), but bullies do not usually act alone. Bullies tend to like others who engage in similar behaviors, those who help them hurt someone or those who reinforce their behavior. Those who join in with bullies and help them to bully someone are called assistants and people who laugh and encourage bullying when it is taking place are called reinforcers.

- Figure 1 - People involved in a bullying event.

- In the figure, you can see the ringleader (the person who starts and leads bullying), the assistants or reinforces (those who help ringleaders hurt someone or reinforce their behavior), the defenders (people who help victims of bullying), and the bystanders (those who know about bullying but ignore it).

There are also people who help victims of bullying in some way and they are known as defenders. However, bullying is often reinforced by people who know about it but remain silent. These people do not get involved in the bullying situation because they prefer to ignore it, or they do not feel capable of doing something to stop it. People who know about bullying but ignore it are called bystanders. Bystanders may play a key role in stopping bullying, or in allowing it to continue happening. In addition to all of these roles, other people can be what researchers call bully/victims, meaning kids who are both bullies and victims.

Health Consequences of Bullying

Bullying significantly affects the social, emotional, and academic well-being of both the bullies and the victims. For example, research has shown that victims of bullying are more likely to report symptoms of depression, low self-esteem, and anxiety. Victims are also more likely to experience social exclusion, they report less life satisfaction, have more absences from school, and often have poor academic performance. Bullies are also more likely to have poor performance in school, as well as problems keeping friends. Bullies are also more likely to report drug and alcohol use and violence later in adult life [1]. Bullying also has negative consequences for bystanders. Research has revealed that kids who observe bullying have difficulties concentrating and may experience depression or distrust of others [4].

Why Do Some Children Bully Others?

We asked students why some people bully others, and some students said that bullying is motivated by boredom. They explained that bullying may be a way for bullies to spend their time when they feel bored. They also said that bullying may be done as a joke rather than as an act to hurt someone. However, research has shown that bullying is not explained by boredom. Bullying may be explained by what researchers call the dominance hypothesis. This hypothesis says that some children who bully are driven by the desire to have a dominant status in the peer group. This means that bullies expect to experience positive outcomes from their bullying, such as the approval of their social group, or high popularity, and sometimes they actually get these things through bullying. It’s important to know that even when bullies are not well liked by their classmates, they may still be seen as popular, powerful, and cool by members of their own group. So, other students might assist or reinforce bullying, so that they can also been seen as cool, or to avoid being bullied themselves. Bullies usually choose victims who are unaggressive, insecure of themselves, physically weak, have few or no friends, or who are rejected in school. By dominating victims like this, bullies can repeatedly demonstrate their power to the rest of the group, reinforcing their popular position without the fear of being confronted by the victim.

Other researchers have demonstrated that bullies are also driven by impulsivity, meaning that they tend to act without prior reflection or thought and that they also show less empathy, which is the ability to understand what others feel. When bullies ignore the feelings of others, it could be because they are not able to see that the victims are suffering, which might make the bullying behavior more likely. Researchers have also found that bullies show something called high moral disengagement. This is a term used by psychologists to describe the process by which someone convinces himself/herself that standards of right and wrong (for example, that hurting people is negative and inappropriate) do not apply to them. Thus, bullies may think that aggressive behaviors are acceptable and, because of this, they might hurt other people [1].

How is Research on Bullying Performed?

Psychological research can help to prevent the severe mental health problems associated with bullying by analyzing which factors put a child at risk of being bullied. To learn what these risk factors are, researchers ask questions of people who may be suffering from or performing bullying. The researchers ask questions about how the bullies or victims feel and what their relationships with other people are like. Researchers also ask whether the bullies/victims have trouble making friends with other people, or if they think they do well at school.

Based on this type of research, we did a study to understand how suffering from bullying or performing bullying behavior is related to having friends who understand you, who are there so you can tell them about your problems, and who offer to help you solve your problems. We also wanted to know how big of a role popularity among peers plays, for both bullies and victims. Additionally, we wanted to know whether the factors that influence bullying are the same whether bullying occurs in or if it occurs over the Internet (cyberbullying), when the victim and bully do not directly see each another.

To examine these topics, researchers use self-reported scales, which are a type of survey, which involves asking a participant about their feelings, attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors. These scales contain a series of questions about a given topic that we wish to investigate. Study participants must indicate if something similar to what the questions describe has happened to them, or if they agree or disagree with the statements that appear in the scale. For our study, we selected scales that had been used before with students between 10 and 12 years old, in different countries. One scale measured bullying. Students stated whether they had performed or suffered from a specific behavior in the last 3 months, on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (several times a week). For example, they were asked if they had “written embarrassing jokes, rumors, gossip, or comments about a classmate on the Internet.” Another scale measured the quality of the study participants’ friendships. They had to indicate to what extent they agreed with each sentence on a scale from 1 (agree entirely) to 5 (disagree entirely). Here is an example: “When my friends know that something is bothering me, they ask me about it.” We used another scale to understand how the participants were supported and protected by their friends. This scale went from 1 (never) to 5 (all the time) using questions like: “How often can you count on someone to listen to you when you need to talk?” Finally, we asked the participants what they thought about their own popularity, with questions like “others think I’m popular,” and how they would like to be seen by others, in popularity terms: “I’d like others to think I am a leader,” on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always).

We collected data from students who returned signed forms with their own and their parents’ written consent. We were careful to make sure that the students trusted the research team, so that they provided honest answers. To do this, questionnaires were administered anonymously and contained no information that could identify the participants. After finishing each session, questionnaires were placed inside an empty envelope to show the participants that information was processed confidentially. This way, participants could see that all the questionnaires in their class were mixed together and were not marked in any way to make difficult that anyone could identify their answers. We collected data from 1,058 children (516 females and 542 males), who studied at one of 17 primary schools chosen randomly in the Castilla-La Mancha region of Spain.

Bullying Seems to be Less Frequent among Children with Supportive and Close Friends

First, we classified the participants according to their involvement in bullying. We considered students to be victims of bullying if they reported having suffered at least one of the behaviors included in the questionnaire, several times a week. This gave us 143 children who were victims of bullying and 915 who were uninvolved. We followed the same procedure for categorizing bullies, which resulted in 58 bullies and 1,000 uninvolved children.

After we classified participants into victims or bullies, we looked at how they described themselves, in terms of their friendship support and their popularity. We compared them with non-involved children. The results showed that victims of bullying were less likely to experience closeness to friends than uninvolved children. This was particularly interesting because this result applied regardless of whether the bullying was face-to-face or through the Internet. It seems that children who do not have close friends miss opportunities to gain support from other children when they are bullied, and they have fewer opportunities to defend themselves from bullies.

Furthermore, victims of bullying reported less social support than uninvolved children. Social support involves spending time with others and having somebody who readily supports and offers comfort. The children who did not report such support appeared to be at higher risk of suffering bullying. Additionally, the children who believed they were not popular and felt that they were not well accepted by their peers experienced more bullying.

Regarding the bullies, study participants who wanted to be seen as leaders among their peers were more likely to be involved in bullying behaviors. It could be that these children engage in bullying as a way to become more popular or because they are supported by others when they perform bullying behaviors.

Conclusion

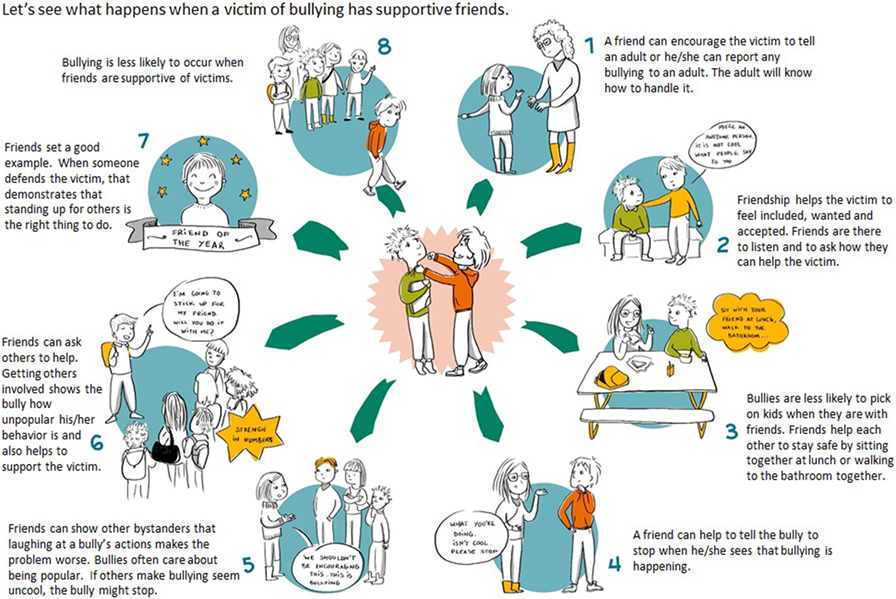

Our study suggests that bullying is less frequent in a circle of good friends. In fact, our results show that having someone to spend time with, someone who helps you and offers you consolation, decreases your chances of suffering from bullying. We know that supporting victims is never easy, but helping others can be crucial when it comes to minimizing bullying. Providing this help does not mean directly confronting the bully. Even just listening to your friends can make a difference, because your friends will feel included and liked. Bullies often target people when they are alone, so, offer to sit with a friend at lunch or walk to the bathroom with her/him. You can also inform an adult, so they can help solve the problem, or you can encourage your friend to talk to an adult. In Figure 2, you can see how support from a friend can help to make bullying less likely to occur in the future.

- Figure 2 - Help from supportive friends in bullying situations.

- The figure shows how one child got bullied, but because people decided to support him, he was less likely to be bullied in the future.

Whether or not you are friends with the victim, you should be sympathetic to his/her situation and report any bullying to an adult you trust. Saying nothing could make it worse for everyone. The bully will think it is ok to keep treating others that way. It is also important not reinforce the bully by laughing at the bully’s behavior. This makes the problem worse, because the bully may think that she/he is popular and powerful. As other researcher have stated, if fewer children took on the role of reinforcer when witnessing bullying, and if the group refused to assign a high status to those who bully, an important reward for bullying others would be lost [5]… and eventually, bullying may stop.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank young reviewers and mentor for the suggestions that have contributed to a tighter and more comprehensive work. We would also like to thank the artist Ana B. Delgado (anadelgado017@gmail.com) for creating the illustrations for this article.

Original Article Reference

↑ Navarro, R., Yubero, S., and Larrañaga, E. 2015. Psychosocial risk factors for involvement in bullying behaviors: empirical comparison between cyberbullying and social bullying victims and bullies. Sch. Ment. Health 7(4):235–48. doi:10.1007/s12310-015-9157-9

References

[1] ↑ Smith, P. K. 2016. Bullying: definition, types, causes, consequences and intervention. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 10(9):519–32. doi:10.1111/spc3.12266

[2] ↑ Navarro, R., Yubero, S., and Larrañaga, E. 2016. Cyberbullying Across the Globe. Gender, Family, and Mental Health. Netherlands: Springer.

[3] ↑ Menesini, E., and Salmivalli, C. 2017. Bullying in schools: the state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 22(sup1):240–53. doi:10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740

[4] ↑ Rivers, I., Poteat, V. P., Noret, N., and Ashurst, N. 2009. Observing bullying at school: the mental health implications of witness status. Sch. Psychol. Q. 24(4):211–23. doi:10.1037/a0018164

[5] ↑ Salmivalli, C., Voeten, M., and Poskiparta, E. 2011. Bystanders matter: associations between reinforcing, defending, and the frequency of bullying behavior in classrooms. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 40(5):668–76. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.597090