Abstract

When a plant is battered and nearly destroyed by the rain, its survival is uncertain, but as the sun comes up and shines on it, the plant starts to recover. Over time, not only does the plant get better but it also comes back stronger. This is growth, and it can happen to us too after an adversity. An adversity is something that is very difficult to deal with and causes us to be upset, have unhappy thoughts, and might even make us cry. But what if something good can come from that bad experience? What if we can learn something that helps us to be different, and maybe better than before? Growth is not just about getting bigger; it can mean changing as a person too. Growth will not stop the adversity from being upsetting, but can lead to powerful, positive changes in a person.

Sometimes life can be tough. People get ill or injured, or loved ones die. Sometimes sport can be tough, too. For example, a gymnast may not make the national team and no longer be able to train with the same squad, or an academy football player may be dropped from the team, crushing their dream to follow in their hero’s footsteps. In sport psychology, we call these extremely unpleasant events adversity. Adversities can make us feel really upset, angry, or sad. In the past, many researchers have spent time looking at what this upset, anger, and sadness can do to us. For example, some researchers focused on the bad memories that kept coming back after the adversities. However, researchers have started to find that even though bad things can happen because of adversities, some good things can also come out of those horrible experiences. This is like a battered plant that recovers from a storm and comes out of it stronger. The young athlete who fails in his or her sport may be more motivated to work hard at that sport to achieve success. The athlete might even discover that he or she is much better in a different position on the team. Or the athlete may now have time to enjoy a different sport, activity, or spend time with friends. In sport psychology, we call this growth.

What Happens When We Experience Adversity?

Adversities can happen to anyone, whether you are an adult or a child. Adversities are experiences or events that we think are very serious, unpleasant, and meaningful. Everyone has their own ideas of whether something is an adversity or not, but what matters most is how horrible the experience or event is for the person who experiences it. Adversity in sports is usually more than having an argument with a teammate or losing a league match. When an adversity happens, it can be very upsetting, and the person might not know how to make things better. People facing adversities might feel like something very important to them is ruined and that their hopes for the future are destroyed. Things that they used to believe were achievable might now feel impossible. Adversity might mean that people can not reach their goals, like becoming a professional footballer or participating in the Olympic Games. Adversities can also happen outside of sport. Children whose parents have split up may feel like an important part of their lives has changed, because a parent who always supported them is no longer around.

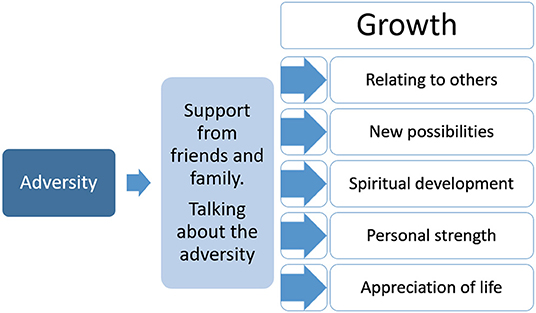

For some people, it might be difficult to stop thinking about the thing that happened. They may find that memories pop into their heads even when they do not want them to, like when trying to concentrate at school. Some people even find that the adversity causes bad dreams. It is very likely that an adversity will make people feel angry or upset. It may be difficult to talk to anyone about it and people may want to spend more time alone. They might feel like crying more than usual or may get into more arguments with others. They will probably feel really bad about what has happened to them, but over time may think about it less. With support from friends and family, and by talking to others about their feelings, sometimes good things can come out of their bad experiences.

What If Adversity Could Lead to Something Positive?

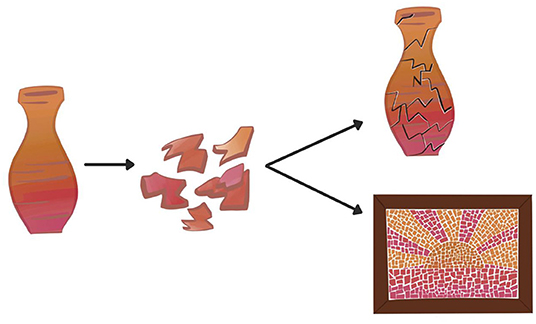

Even though adversities can be upsetting, many people have told researchers that some good things have come from their horrible experiences. In 2005, two researchers came up with a really useful way of describing this [1]. Imagine a beautiful vase sitting on your windowsill. One day, the vase gets knocked over and shatters on the floor. You have a couple of options: 1) You could glue the vase back together. The vase would be repaired, but it might not look as good anymore. Water might leak through the cracks, and it would be fragile and likely to break again. 2) You could take the broken vase pieces and make something new, like a beautiful mosaic to decorate the room. The vase would not be a vase anymore, but it might be better (Figure 1).

- Figure 1 - A smashed vase shows how we can respond the adversity.

- Once broken the vase can be stuck back together but it is still broken, or it can be transformed into something better (the mosaic).

Growth for a person is like the vase that is transformed into the mosaic. The person may be different, but maybe even better than before. The adversity may still be upsetting, but it can lead to powerful, positive changes in a person. These changes can happen when people facing adversities have other people around them who care and are prepared to listen and be supportive. Talking to those people and not keeping the upsetting thoughts and feelings inside is really important to help growth occur. For young athletes, this support may come from family, coaches, teachers, or friends.

Researchers made a questionnaire called the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) that researchers can use to study growth [2]. The questionnaire has 21 statements that measure five different signs that can tell us whether someone has grown after an adversity. For each statement, people are asked to select a score from 0 to 5 to show how much they agree with that statement, where 0 is “never experienced” and 5 is “experienced a lot.” The higher the score, the more likely someone is to have grown. These five signs are:

1. Appreciation of life: Sometimes when people have experienced an adversity such as a bad injury, they tell researchers that they have changed their minds about what is important to them. One of the statements on the PTGI that measures appreciation of life is, “I have different priorities about what is important in life.” In one study, an Olympic swimmer said that when he gave up swimming, he was able to enjoy life more. He told the researchers he loved spending more time with his family [3].

2. Relating to others: After an adversity, athletes sometimes talk about how their friendships and relationships get better. This might be because they have spent more time with friends and family or have needed their support to get through the experience. One of the statements that measures whether someone has improved how well they get on with others is, “I put effort into my relationships.” Sometimes, athletes who have recovered from injuries tell researchers that they have a better understanding of how teammates feel when they are injured.

3. New possibilities: Adversities sometimes give people the chance to try new things that they may not have been able to do before. They may have more time to find new things that they enjoy. For example, a footballer who had to give up his sport because of a knee injury may find that he is able to play other sports instead. Or he may discover that he really enjoys drama and turn out to be great at acting. One of the statements that measures whether people can see new possibilities in life is, “I developed new interests.”

4. Spiritual development: This is when people who have had an adversity feel more religious or have a better understanding of the meaning of life. For children, this may involve asking questions about the purpose of life or whether God exists. One of the statements that measures spiritual development is, “I have stronger religious faith.”

5. Personal strength: This is not about physical strength. Instead, after an adversity, people may believe they can manage things better than before. One of the statements that measures personal strength is, “I am stronger than I thought.” Some adults might say, “it made me stronger,” which means they believe they are more able to deal with other horrible events. A young athlete who has recovered from a very bad injury might be able to cope better if something else nasty happens in the future.

The process that leads to growth is shown in Figure 2.

- Figure 2 - The process of growth in response to adversity happens when we get support from friends and family and when we are ready to talk about the adversity.

- Growth can be recognized by an increase in the five signs mentioned.

Not everyone who experiences an adversity will show signs of growth. When people do, they might not believe that all five signs of growth happened to them, sometimes it is just one or two. Also, there are other good things that can happen after an adversity that do not fit into one of the five areas above. For example, what is really interesting is that when elite athletes talk about growth, they often say that they got better at their sports as a result of their adversities—even when the adversity involved injury! One of the most famous swimmers ever, Michael Phelps, wrote in his autobiography that when he was a child his teacher said that he would never be good at anything. Even though it was very upsetting, he believes that it made him more determined to become a world-class swimmer. Other athletes find that, when they fail, it makes them realize how much they want to do well in their sports. This can motivate them to work hard on their skills to become the best athletes they can be. Even if people experience growth, this does not mean that the adversity was a good thing; they might still feel sad or upset about it. But growth means that because we have gone through the adversity, there are some things in our lives that improve. Not everyone believes they have grown after adversity, and that is ok too.

Take-Home Message

Life has its ups and downs. Even when adversity happens and it makes us feel upset and angry, some good things can still come from it. These good things are called growth. Growth can involve improvements in five areas: appreciation of life, relating to others, new possibilities, spiritual development, and personal strength. When we talk to supportive people around us, then growth is more likely to happen. So, if something bad happens to you, talking to people about it is a really important thing to do!

Glossary

Sport Psychology: ↑ This is the study of how the mind impacts on how we perform in sport. It can focus on how we feel, how we think and how we behave.

Adversity: ↑ This is an event or experience that we think is negative and upsetting.

Growth: ↑ Involves the positive things that we can see in ourselves after we have experienced an adversity.

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: ↑ This is a questionnaire that measures growth after (or post) adversity. Sometimes we refer to adversities as traumatic.

Conflict of Interest

NH was employed by Embrace Performance.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Joseph S, and Linley A. 2005. Positive adjustment to threatening events: an organismic valuing theory of growth through adversity. Rev. General Psychol. 9:262–280. doi: 10.1037/1089–2680.9.3.262

[2] ↑ Tedeschi RG, and Calhoun LG. 1996. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Traumat. Stress 9:455–471. doi: 10.10007/BF02103658

[3] ↑ Howells K, and Fletcher D. 2016. Adversarial growth in Olympic swimmers: constructive reality or illusory self-deception? J. Sport Exercise Psychol. 38:173–186. doi: 10.1123/jsep.2015-0159