Abstract

The Internet can provide any information imaginable, leading some people to wonder why they should bother learning or memorizing things. You still need your brain, because it can do things with information that the Internet cannot. Your brain puts information into a larger context; this not only helps you see how concepts are connected, it actually helps you to understand things differently. Your brain is also better at picking the right information from memory for the mental job at hand and at giving you access to that information quickly. The Internet can’t replace your brain, but it can complement it if you understand what each does best.

Introduction

You’ve probably caught yourself in school wondering, “Why do I need to memorize this?” The Internet makes knowing something nearly as easy as lifting a finger. Why memorize the capitals of all 50 states when you can Google them in seconds? And were you to look up the capital of, say, Arizona, you’d have access not only to its name (Phoenix) but other facts about it, for example that it was originally named “Pumpkinville.” (Oddly, there weren’t even any pumpkins growing there, just melons that sort of looked like pumpkins). So what’s the point of memorization? Have our computers and smart phones replaced the need for memory?

You still need your brain. You can think of your brain like a tool box and the Internet like a hardware store. The Internet can provide any information imaginable, but your brain is much better at picking the right information from memory for the mental job you are trying to do. The hardware store is full of specialty items you wouldn’t use on a regular basis. Your tool box should contain practical tools you know how to use well. And, although Internet searches are fast, your brain gives you access to that information even faster. Think of Googling something as driving to a hardware store every time you need to use a tool! While the Internet can’t replace your brain, it can complement it, if you understand what each does best.

Picking the Right Information

What happens when you’re reading and come across a word you don’t know? You don’t always need to look it up. This is because your brain uses the context of what you are reading to figure out the unfamiliar word. That is, your brain uses the other words you do know in the sentence and paragraph to help you understand the meaning of the new word. Consider the following sentence:

- Paul went to the haberdashery to buy a new suit. Audrey waited in the car, because she doesn’t like stores that don’t sell women’s clothing.

Even if you don’t know the word haberdashery, the surrounding words in the first sentence tell you that Paul will buy a suit, so you would (reasonably) guess that a haberdashery is a clothing store, or at least, a place that sells clothing along with other items. The second sentence tells you that a haberdashery doesn’t sell women’s clothing, so you can (again, reasonably) guess that it sells men’s clothing. Your brain pieces together the meaning of the word, like a puzzle.

More surprising, context is important even when you already know the definition of a word. Take the example of Amelia Bedelia, a fictional housekeeper who gets into funny situations because she takes instructions too literally. In the stories, Amelia Bedelia does exactly what her bosses ask. When instructed to dust the furniture, she proceeds to cover the furniture in dust (noting to herself, “At my house, we undust the furniture.”) Whether she is “drawing” the curtains with a pen and paper, or “stamping” letters into the floor with her feet, she provides a lot of good examples of the way words can mean more than one thing, depending on the context.

Amelia Bedelia is not all wrong. Does “dusting” mean to add dust or to take it away? It depends whether you’re a detective dusting the furniture for fingerprints or a housekeeper cleaning it. You could have guessed Amelia was meant to clean the furniture, because your brain uses the context in which the word appears. You know a housekeeper’s job is to clean, not to investigate a crime scene.

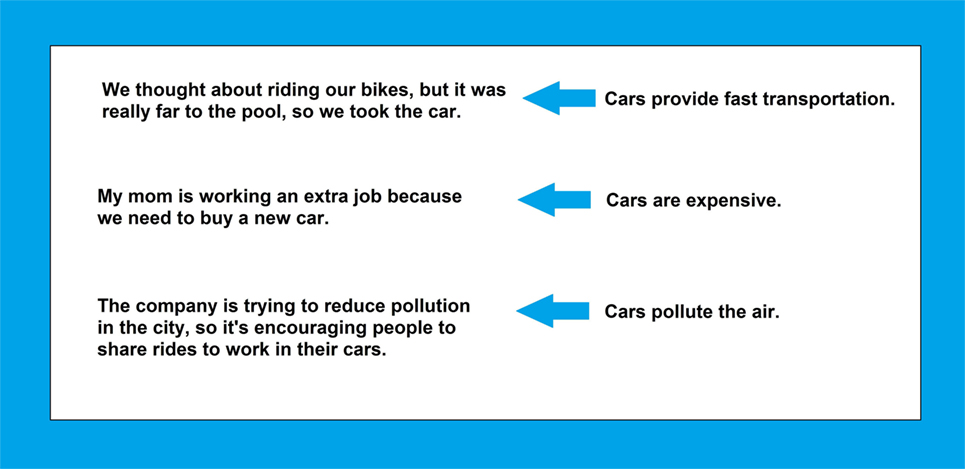

So far, we’ve seen that your brain can use context to figure out a completely unfamiliar word (“haberdashery”) or to tell you which of two different meanings for a word is appropriate (“dust”). But, even if a word has a single meaning, you need to use context to determine the feature of meaning that you’re supposed to pay attention to. For example, take a look at these sentences using the word “car.”

- We thought about riding our bikes, but it was really far to the pool, so we took the car.

- My mom is working an extra job because we need to buy a new car.

- The company is trying to reduce pollution in the city, so it’s encouraging people to share rides to work in their cars.

Unlike our examples using the word “dust,” the word “car” has the same meaning in each of these examples. To fully understand the point of the sentence, however, you need to pay attention to the important feature of the meaning.

Cars have many characteristics. They are fast, expensive, and pollution-causing. Cars come in different colors and sizes, are made by humans, require a license to operate, and so on. Usually, just one of these characteristics is important for understanding a situation. Note that as you read the sentence:

- We thought about riding our bikes, but it was really far to the pool, so we took the car.

you think of just one characteristic of cars: “right, they took the car because it’s faster.” You don’t think “they took the car because its faster…but you know, cars are also expensive and pollute the air.” Your brain is terrific at pulling from your memory the exact feature of meaning that fits the context. When you read:

- Dan decided to join us, so we had to take two cars.

you immediately think about the fact that cars have a limited seating capacity. Suppose you didn’t know that fact. The sentence would be confusing. Perhaps you’d Google the word “car” to try to puzzle out why Dan joining the trip meant that two cars were necessary. Google returns over 5 million results for the search term “cars!” How long would it take to review these sites before you figure out that cars carry a limited number of passengers?

So, that’s one way that your brain is superior to Google—words change their meaning with context, and the brain is better at meeting that challenge. But what about the other obvious advantage of the Internet—isn’t it fast and convenient to look things up?

Speed

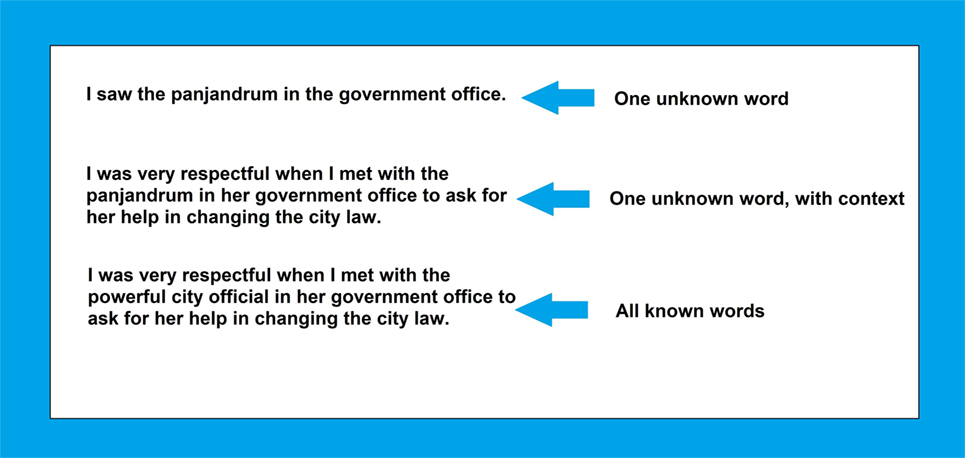

Looking something up on the Internet may be faster than looking the same thing up in a book, but both methods are much slower than finding that information in your memory. This makes a difference because speed is important to reading. If you slow down too much, you can’t connect sentences and clauses; as you’re reading one sentence you forget the one you just finished. You might remember experiencing this when you were first learning to read, and had to slowly sound out each word. The same thing can still happen, but for a different reason. Now, instead of letters, it’s words you don’t know that slow you down. Consider these three sentences:

- I saw the panjandrum in the government office.

- I was very respectful when I met with the panjandrum in her government office to ask for her help in changing the city law.

- I was very respectful when I met with the powerful official in her government office to ask for her help in changing the city law.

These sentences illustrate the importance of memory to reading.

For the last sentence, all of the words are in your memory, and reading proceeds smoothly. The second sentence contains one unknown word, but plenty of context to give you a good idea of what that word means. You can figure out that the panjandrum must be someone who can help you change laws that has a government office. Reading the second sentence is still not quite as smooth as the third. An unknown word such as “panjandrum” is like a speed bump—it slows you down, but you are able to get through it. In the first sentence, however, there’s no context to help. “Panjandrum” is not a speed bump, it’s a flat tire. To proceed, you would need to look the word up, and that’s like putting your car in park, getting out, and calling for help. There’s no doubt that it’s faster to look up a word definition with Google than by using a paper dictionary, but it’s still much slower and more disruptive than either retrieving the meaning of the word from memory, or using the context to puzzle out the meaning.

Conclusion

Think back to the analogy of your brain as a tool box and the Internet as a hardware store. The first section of this article explains why the context provided by a sentence is important for understanding the meaning of a word. Similarly, knowing the different ways you can use your tools helps you get the most out of them. Just like the word “dust” has two meanings (which are actually opposites), a hammer can be used to both add and remove nails. To make sense of information, you need to know how concepts are connected, often in ways that would be difficult to look up on the Internet. You would be unlikely to find a hammer labeled as a “nail remover” in a hardware store, just as you would be unlikely to see a car advertised as an “environment polluter” at a car dealership.

The second section of this article points out the importance of speed in putting together information from what you read. Similarly, practice in finding and using your tools helps you get a job done more quickly. While a hardware store has a much larger selection, you can find the tools in your own toolbox more quickly and use them more effectively. That’s an obvious advantage, but the hardware store does have your personal toolbox beat in one way: they’ve got everything. Likewise, the Internet has all the information you might need, but your brain doesn’t.

Given that your brain’s storage space is limited, what should you pick to learn? You need to use some mental tools frequently, for example letters and numbers. These are the hammer and nails of your toolbox. You’ll want to memorize the things that come up most frequently in your daily life. Luckily, school is designed around helping you learn things you will encounter again and again. Learning can also happen outside of school. When you read, you develop contextual knowledge in a way that’s impossible from memorizing definitions alone. Reading books that you enjoy is a great way to do this. Video games, comic books, and magazines all provide opportunities to practice reading as well.

People and computers have complementary skills. This means that computers are very good at some tasks that humans are bad at, and humans are good at certain kinds of tasks that computers cannot perform well. Your brain is good at pulling up the right information for you quickly, and at putting things into context. The Internet has more information on it than a single human being could ever memorize. While you can’t replace your brain with Google, you can use the Internet wisely if you remember what both your brain and the Internet do best.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.