Abstract

The ability to taste brings us some of the finest things in life: the sweetness of candy, the saltiness of chips, and the sourness of lemonade. We all know it starts on the tongue, but how does it really work? Scientists have discovered that taste comes from a chain reaction that starts with sensitive proteins on your tongue, races through taste buds, enters your nerves, and ends in your brain. One of the most amazing findings is that taste sensitivity varies from person to person. Each of us lives in a unique taste world, making everyone different in the foods they love and hate.

Introduction

Think of your favorite food. Is it pizza? Chocolate? Sushi? Imagine your favorite treat and the pleasure you get from eating it. What about a food you dislike? Foods have many different properties that contribute to enjoyment: smell, temperature, and even how they feel in your mouth. One of the most important properties of food is taste, the combination of sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and savory sensations coming from your tongue. How are these signals conveyed from the mouth to the brain? This has long been a mystery. However, scientists looking closely have uncovered remarkable details about the pieces making up the taste system, and how these pieces fit together [1].

A Closer Look at Your Tongue

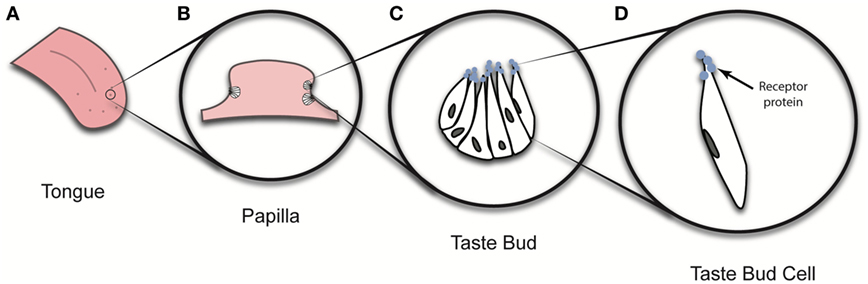

What do we see when we stick out our tongues? Bumps. Lots of bumps. Most people think they are taste buds, but it is a little more complicated than that (Figure 1). The bumps we see are called papillae, and they are a special tough part of our skin. The real taste buds are made up of delicate cells nestled like sections of an orange beneath the surface of the papillae, where they are well protected. Only the tips of the taste buds poke through to the surface of the tongue. The taste buds cannot be seen with the naked eye, but if you could zoom in, you would see that each of our papillae contains thousands of taste buds, all peeking out [2].

- Figure 1 - The structure of the tongue.

- A. The bumps on the surface of the tongue are called papillae. B. Taste buds are hidden beneath the surface of the papillae and barely poke out. C. Each taste bud is made up of a cluster of cells, which are packed together like segments of an orange. D. The cells making up taste buds store special taste receptor proteins at their tips, which respond to particles in food. Each taste bud cell is attached to nerves at its base, as shown in Figure 2.

Taste Detectors

At their very tips, where they poke out from the tongue, each taste bud cell stores tiny proteins called taste receptors (Figure 1) [3]. Thousands of different proteins are found in our bodies, and each plays a special role in the body’s structure and function. The role of taste receptor proteins is to detect substances in your mouth, such as food particles. There are five specialized kinds of taste receptor proteins, and each kind detects particles with one of five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and savory (the “meaty” aspect of foods such as soup broth). Taste receptors activate when chewed food mixes with saliva, then flows over and around the papillae like a mushy river. The receptor proteins ignore most of the mix, but when they detect their target food particles they react, notifying their cells that a taste substance has been detected. This process can be imagined as if the receptors are locks and the food particles are keys. Just as a lock opens only with its matching key, a taste receptor reacts only to its matching type of food particle.

Sending a Signal

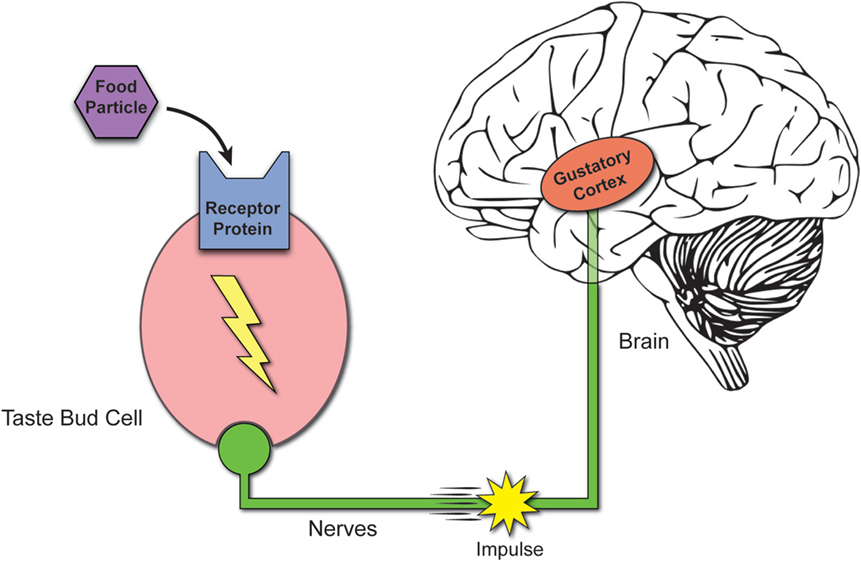

When a taste bud cell is notified that a substance such as food has been detected, it goes into action (Figure 2). The taste bud puts dozens of proteins inside the cell to work. These proteins cooperate, rapidly shifting electrically charged atoms called ions here and there, to produce a tiny electrical current inside the cell [2]. This impulse is so tiny you cannot feel it. However, it is detected by the nerves in your tongue, which are specialists at detecting and passing on electric signals. When the nerves in your tongue receive signals from taste bud cells, they pass them on to more nerves and then more, sending the message racing out the back of your mouth, up through a tiny hole in your skull, and into your brain. There, your gustatory cortex (the taste center of your brain) finishes the job of telling you, which taste you perceive, sweet, salty, bitter, sour, or savory.

- Figure 2 - Taste signals.

- Taste signals begin when food particles are sensed by receptor proteins on the taste bud cells. When the receptor proteins sense different kinds of particles, they order their taste bud cell to send a small current to the nervous system, which relays the impulse to the brain. This diagram is simplified and shows a taste bud cell with one receptor protein. In reality, each taste bud cell has millions of receptor proteins.

Differences in Sense of Taste

The basic taste system is the same for all of us. Even toddlers pucker their faces at sour lemons, smile when tasting sweet things, and dislike bitterness. However, people do differ from each other in important ways. You have probably noticed that some of us are more sensitive to tastes than others. For example, vegetables in the Brussels sprouts family contain a substance called goitrin that is strongly bitter and disgusting to some people, but other people can barely taste it. Why is this? One reason is that different people have different numbers of taste buds [1]. Each taste bud cell adds a little bit to the strength of a taste, so people with more taste buds are more sensitive. This holds true for all tastes, not just bitter. Scientists even have names for people with different sensitivity levels. People with the lowest overall sensitivity are called “non-tasters.” Those in the middle are called “medium tasters.” Those with the greatest sensitivity are called “super tasters.” Which do you think you are? What about your friends?

Be a Taste Researcher

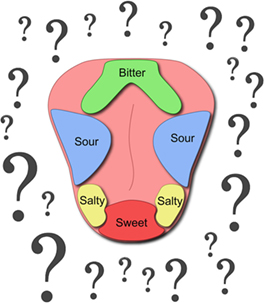

Researchers around the world investigate the process of taste because taste affects what people eat, and what people eat affects their health [1]. There is even some taste research you can do in your own kitchen. One theory you can investigate is that taste sensitivity is laid out like a map on your tongue. For many, many years, books have taught us that salty and sweet tastes are sensed at the tip of the tongue, while bitter is sensed at the back and sour at the sides (Box 1, figure). The center of the tongue, which has few taste buds, is often left blank. However, taste researchers now believe that taste sensitivity does not follow a simple map. They say tastes can be perceived everywhere on the tongue. Try testing yourself using the experiment in the Do-it-Yourself (Box 1). How well does taste sensitivity on your own tongue fit the map?

Box 1. Do-it-Yourself: Testing the Tongue Map

Many books and magazines say taste sensitivity follows a map on your tongue: the front is for salty and sweet, the back is for bitter, and sour is at the sides (figure). (Savory, which is a more recent discovery, is usually left out.) This experiment will test the sensitivity of different regions of your tongue to sweet, sour, and salty tastes, so you can compare your own patterns with the map.

Supplies

Lemon juice.

Salt.

Sugar.

Three small glasses of water.

Tablespoon.

Q-Tips.

Procedures

Wash your hands.

Prepare taste testing solutions:

Add a tablespoon of lemon juice to the first glass of water.

Add a tablespoon of salt to the second glass.

Add a tablespoon of sugar to the third glass.

Stir each glass well, rinsing the spoon between solutions. It is fine if the sugar and salt don’t dissolve.

Dip a Q-Tip in the salt solution and dab it on the back of your tongue. Write down what you taste. Repeat for the sides, center, and front of your tongue. Try other locations on the tongue, too.

Try the test using the sweet and salty solutions. Make sure to use different Q-Tips.

Results

Which regions of your tongue can sense each taste? Do they match the taste map? Try the experiment with your friends. Do they have the same patterns of sensitivity you do?

Glossary

Papillae: ↑ Bumps of tough skin on the surface of the tongue. They protect taste buds inside them.

Taste Bud: ↑ Bundle of cells specialized to detect taste.

Taste Receptor: ↑ Tiny protein found on the tips of taste buds, which responds to particles of food.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Bradbury, J. 2004. Taste perception: cracking the code. PLoS Biol. 2(3):E64. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020064

[2] ↑ Smith, D. V., and Margolskee, R. F. 2001. Making sense of taste. Sci. Am. 284:32–9. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0301-32

[3] ↑ Chaudhari, N., and Roper, S. D. 2010. The cell biology of taste. J. Cell. Biol. 190:285–96. doi:10.1083/jcb.201003144