Abstract

One way people learn new words is through reading books and stories. Little kids love hearing their favorite stories over and over and are also very good at learning new words. We wondered if reading the same stories could be helping preschool kids learn new words. Our research tested if it was better to read the same stories over and over or to read a few different stories. Here, we tell you about three studies that show preschool kids learn more words from reading the same stories over and over. Our research suggests that it is easier to learn new words from stories when you have heard the story before and know what is going to happen.

We know little kids like hearing stories and will ask to hear the same story over and over again. You may have noticed this if you have ever read a story to a younger sibling. Kids learn a lot of things from stories. They can learn about colors, shapes, numbers, relationships, and places—and they can learn new words. You probably learn a lot of new words from reading, too. Kids who hear more stories learn more words than kids who hear fewer stories. Kids who hear lots of stories are also more likely to do better at school. So, we know that hearing stories helps kids learn new words, but could we help kids learn even more?

What Helps Learning from Storybooks?

Kids learn best from stories with plots that are easy to understand and relate to. They also learn better from books with photos than from books with cartoon-style drawings [1]. We know that pointing to things in the pictures helps kids learn words from stories. Giving definitions of new words is helpful too, and so is asking the kids questions about things mentioned in the story. The more times kids hear the new words the more chance they have of learning them, so repeating the words is really helpful in storybooks.

We know kids love hearing the same stories over and over, so we wondered whether this was helpful for word learning. This is what our studies are about.

Our Studies

Do kids learn more words from hearing the same story over and over or from hearing different stories? Our studies will tell us.

If we want to see if kids learn new words from hearing a book, there are different ways we could do this. We would, of course, read them a story and then measure how many words from the story they know. But is it really that simple? How would we know that the kids did not already know those words before they heard the stories? We have a really fun solution: we write our own storybooks so we can put special words in them! These special words are called “target words.” The special words we use are made-up words like “sprock” and “manu.” They sound like real words but we make them up. That way, we can know that kids do not already know the words before we even read the stories. Lots of studies use made-up words like these for the same reason. One famous study is “the Wug Test” [2]. Kids have not heard the word wug before, but if you tell them “Here is a wug, here is another wug, now there are two ___” they know the next word is “wugs.”

The special words in our stories are names for weird objects. Like the words, we use weird objects so we know that kids do not already have a name for them. These weird objects are called “novel objects” because they are new to the kids. Take a look at an example of these special words and weird objects from a set of our storybooks, in Figure 1.

- Figure 1 - These are the target words and novel objects we used in our studies.

Our Stories

For these studies, we wrote nine stories about a girl named Rosie. We tried to make them sound like real storybooks. Each story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Each story has a happy ending. In one story, Rosie makes cookies. But she uses salt instead of sugar by mistake! The cookies taste really bad. But her family still has a nice day.

Each story is nine pages long with nine pictures. We took photos of real people acting out each page. One picture shows Rosie and her father putting cookies into the oven. Then, we used the computer to make the pictures look more like drawings.

In some of the pictures, you can see the novel objects. But the stories are not really about the objects. The stories are really about something Rosie is doing.

There are two weird objects in each story. Each weird object has a name like “sprock.” The name is always the same for the same object. For example, the object with the green wheel is always the “sprock.” We say the name (target word) for each object four times in each story. So, if a child reads a story three times he or she will hear the target words 12 times.

In three stories, the two objects are the “sprock” and the “tannin.” In another set of three stories, the two objects are the “manu” and the “zorch.” In the last set of three stories, the two objects are the “gaz” and the “coodle.” Remember, these are supposed to be new names and weird objects that kids do not know before they read the stories!

Learning and Testing

We wanted to know if kids learn more words from hearing the same story over and over or from hearing different stories. So, we read our stories to two groups of preschool kids. Kids were English-speaking and from average homes in a seaside town in the South of England. The same stories group heard the same story three times in a row. The different stories group heard three different stories instead, but these three different stories had the same target words. Each kid in the same stories group heard one of the stories with “sprock” and “tannin” three times. Each kid in the different stories group heard all three of the different stories with “sprock” and “tannin.” But every kid heard “sprock” and “tannin” 12 times.

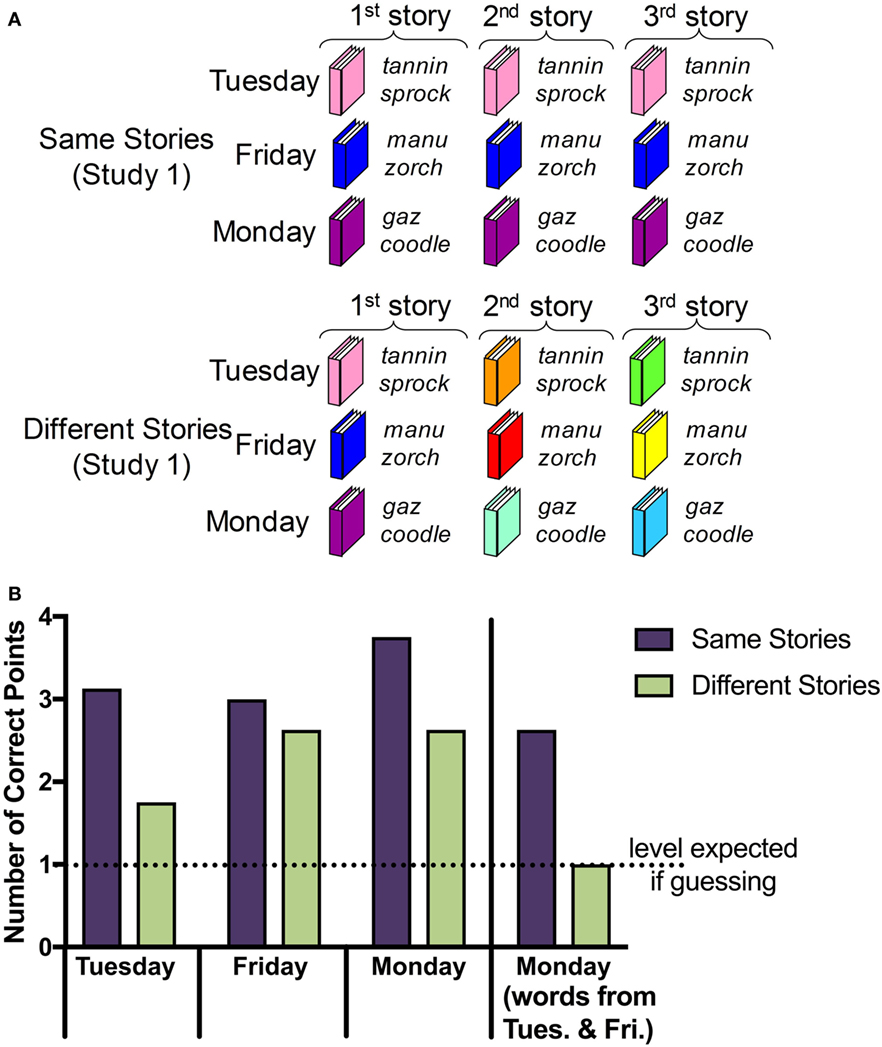

In our first study, we visited kids at home on 3 days over about 1 week. For example, Tuesday and Friday and then Monday. Every time we visited we read three times: either the same story three times or three different stories (take a look at Figure 2A). After we read the stories, we wanted to see if the kids learned the names for the objects. So, we showed them pictures of the novel objects and asked them “can you point to the sprock?” (or one of the words they heard). We asked them to point to each of that day’s objects twice. There were always four pictures on a page, so if kids had not really learned the word and were just guessing, they should point to the correct object for about one of the four questions. So, we asked kids to point out each target object once and did not say whether they were right or wrong. Then, we asked them to point out each target object again. So, if kids pointed to the correct objects for more than about two questions we knew they were not guessing and had really learned the words!

- Figure 2

- A. The story order in our original study. Kids in the same stories group heard a different story each day, but the same story over and over. Kids in the different stories group always heard three different stories, but with the same target words. B. Word learning scores in the original study. Kids in the same stories group always scored higher than kids in the different stories group. This is really important on Monday (the last test) when we tested the kids on the words from Tuesday and Friday again.

Every day that we visited the kids we read them stories with a new pair of words and tested them on that pair of words. Our favorite part of this study was that, on the last day, we also tested them again on the words from the first and second days (which they had not heard since those earlier stories). Would kids remember the words? Would they remember more words from hearing the same stories over and over?

Take a look at Figure 2B. The dark bars show the number of correct points by the kids in the same stories group. The light bars show the number of correct points by the kids in the different stories group. Kids in the same stories group always did better than kids in the different stories group. But what about the last test? Look at the last bars: kids in the same stories group remembered the words really well! And kids in the different stories group did not score any better than if they were just guessing. They had forgotten the words.

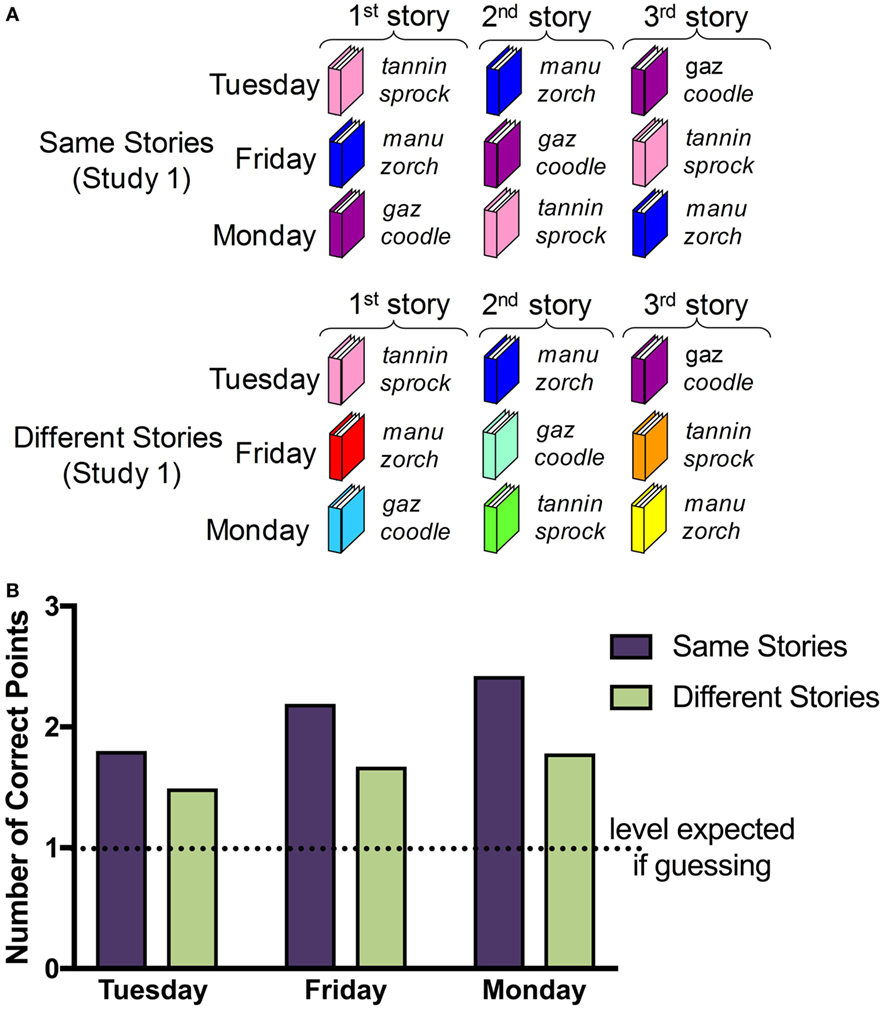

In our second study, we also had a same stories group and a different stories group. Sometimes kids do ask for the same story over and over, but not on the same day. So in this study, the same stories group heard three stories, but they were the same three stories on each day (Figure 3A). In the different stories group, kids heard three different stories every day. This study was a lot harder for kids, because they heard all six target words (but only four times each) each day.

- Figure 3

- A. The story order in the later study. Now, all kids heard three different stories, but for kids in the same stories. group, they were the same three stories each day. For kids in the different stories group, they were always different stories. Notice, this study was a lot harder because kids heard six target words each day of the study. B. Word learning scores in the later study. Kids in the same stories group always scored higher than kids in the different stories group.

Take a look at Figure 3B. Once again, the kids who heard the same stories over and over learned the words really well. They learned more words than the kids who heard different stories.

For another study, we teamed up with a lab in Germany and tested reading the same stories in preschool children diagnosed with developmental language disorder (DLD, previously known as specific language impairment [3]). Children diagnosed with DLD may have trouble speaking and understanding language, and as they get older they may struggle with reading and writing. The lab in Germany translated our storybooks into German. Then, all of the German kids were tested the same way as the English children in the same stories group of the first study. Children diagnosed with DLD did not learn the target words as well as kids in our other studies. However, on the last day of the study, there was no longer a real difference between the children with DLD and the typically developing children. This means that repeating stories is a good idea for children with special needs too.

Summary

Remember that, in each study, all kids heard the target words the same number of times. This means the only difference was whether or not the stories were repeated. Kids learned more words from repeated stories than from different stories. Even when stories were repeated days later, kids still learned more words, so there must be something very special about hearing things over and over again.

But reading and hearing different books are still good for learning, too. It could be that kids hearing the different stories are learning something different. Maybe they are learning more about the different uses of the objects. Or maybe they learn how to use the word correctly in a sentence better. There is still a lot we do not know. Our work in this research area isn’t over yet!

What Does it all Mean?

Kids learn more words from hearing the same stories over and over. It reminds us of how kids like to watch the same TV shows over and over [4]. Sometimes when you watch a movie for the first time it can be a little confusing to follow the story and work out who the key characters are. But when you watch the same movie for a second or even third time, you know what is coming and can think about different parts of the movie because you no longer need to concentrate so hard on the story.

This is what we think is happening here. With each new reading of the story, kids are able to focus on something new: they have time to work out what these novel objects are and to learn their names. Kids hearing different stories are always hearing the story for the first time, so they have to concentrate on understanding the story. They just do not have enough time or brain power to concentrate on anything extra.

It is important to understand how kids learn words. We want to find ways to help kids learn words even better, so we can help everyone do well at school. But understanding how kids learn helps in lots of other ways, too. Not everybody learns to speak in the same way. Some kids take longer to learn language, and some might always find reading difficult. Imagine if we could use storybooks to help some of these kids learn a little bit more. What an easy way to help! Even adults like to hear stories when they already know the ending [5]. Maybe you are learning a second language. Maybe English is a second language to you. Maybe you just find it hard to concentrate when reading. Reading the same stories and books over and over might help you, too.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑ Horst, J. S., Parsons, K. L., and Bryan, N. M. 2011. Get the story straight: contextual repetition promotes word learning from storybooks. Front. Psychol. 2:17. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00017

References

[1] ↑ Simcock, G., and DeLoache, J. 2006. Get the picture? The effects of iconicity on toddlers’ reenactment from picture books. Dev. Psychol. 42(6):1352–7. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1352

[2] ↑ Berko, J. 1958. The child’s learning of English morphology. Word 14:150–77. doi:10.1080/00437956.1958.11659661

[3] ↑ Bishop, D. V., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., Greenhalgh, T., and CATALISE-2 Consortium. 2017. CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development. Phase 2. Terminology. PeerJ Prepr. 5:e2484v2. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.2484v2

[4] ↑ Crawley, A. M., Anderson, D. R., Wilder, A., Williams, M., and Santomero, A. 1999. Effects of repeated exposures to a single episode of the television program Blue’s Clues on the viewing behaviors and comprehension of preschool children. J. Educ. Psychol. 91(4):630–7. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.91.4.630

[5] ↑ Leavitt, J. D., and Christenfeld, N. J. S. 2011. Story spoilers don’t spoil stories. Psychol. Sci. 22(9):1152–4. doi:10.1177/0956797611417007