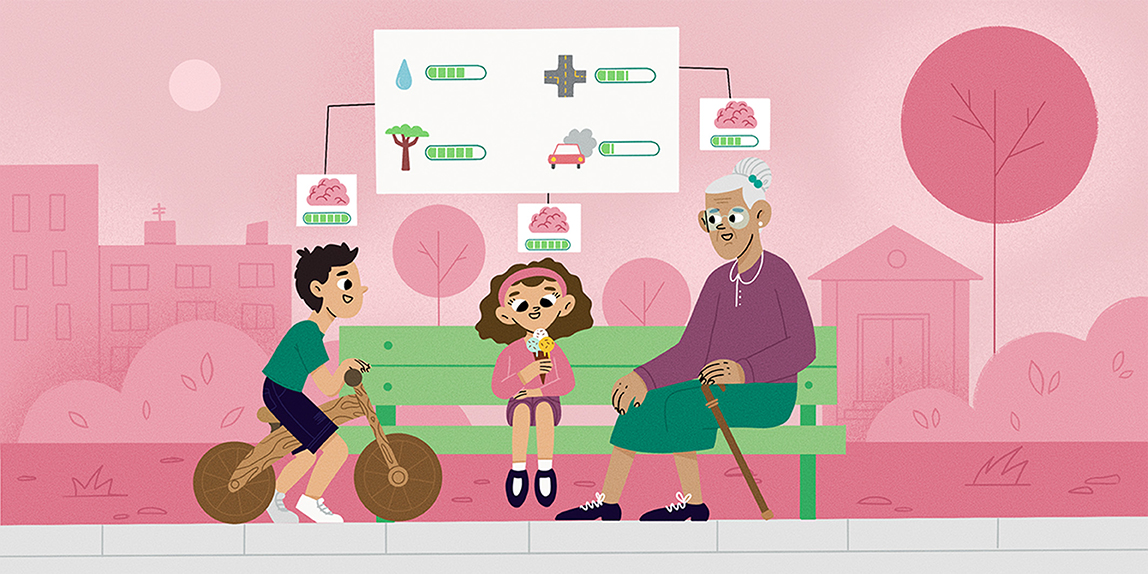

גם בינה מלאכותית משתמשת בקיצורי דרך

בינה מלאכותית (AI) זוכה לעיתים קרובות לשבחים על הביצועים המרשימים שלה במגוון רחב של משימות. עם זאת, מאחורי הצלחות רבות...

סוקרים צעירים

בינה מלאכותית (AI) זוכה לעיתים קרובות לשבחים על הביצועים המרשימים שלה במגוון רחב של משימות. עם זאת, מאחורי הצלחות רבות...

לְרֻבֵּנוּ יש חמישה חושים, שבהם המוח משתמש ליצירַת מוֹדֶל של העולם הנמצא סביבנו. כדי להבין מה קורה בסביבתנו אנו רואים...

בעלי חיים שצדים חיות אחרות כדי להזין את עצמם מכונים 'טורפים'. בעלי חיים ניצודים ידועים כ'טֶרֶף'. מה קורה, לדעתכם, כאשר...

חיידקים מזיקים הם אורגניזמים זעירים שלפעמים עלולים לגרום לבני האדם לחלוֹת בחוּמרה. בדרך כלל, כאשר חיידקים מזיקים נכנסים...

אולי לא הבחנתם בכך שפטריות גדלות על קליפות העצים בשכונות מגוריכם, אך מדענים גילו כי מינֵי פטריות רבים הצטרפו לצד זה של...

דַּמְיְנוּ שאתם מְשׂחקים במשחק וידיאו כל כך מהנה, עד שאינכם מבחינים בכך שמישהו קורא בשמכם. כולכם ודאי יכולים לחשוב על...

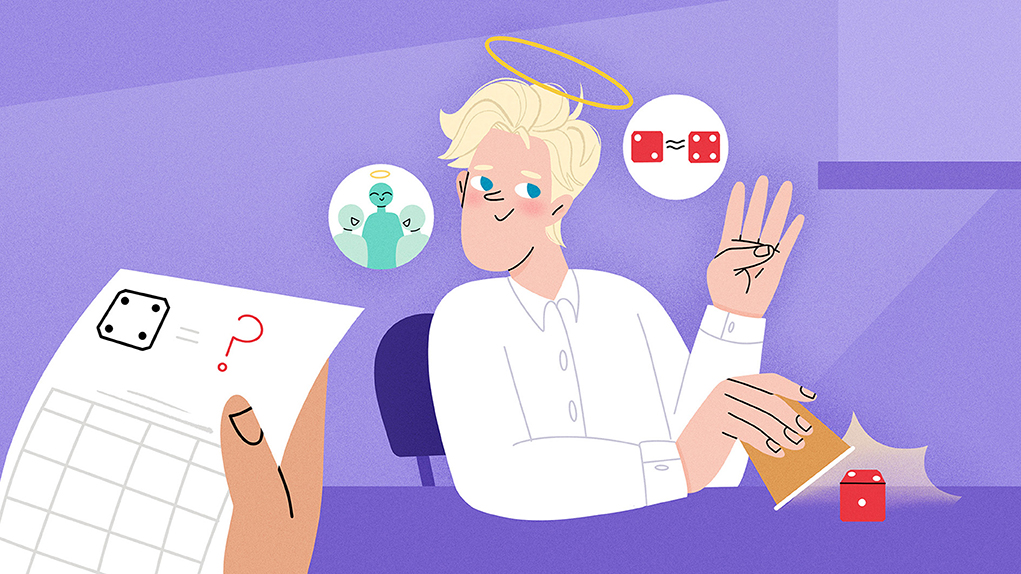

כולנו יודעים שילדים ומבוגרים משקרים לפעמים – אבל מתי הם נוטים לשקר, ועד כמה? ואיך בכלל אפשר לחקור שקרים בצורה מדעית...

מחלות שעוברות באופן טבעי מחיות לבני אדם נקראות זוֹאוֹנוֹסִיס, או מחלות זוֹאוֹנוֹטיוֹת. יותר מ-70% מכלל הזיהומים הנגרמים...

האם אי פעם שמעתם על טָרֶשֶׁת אַמִיוֹטְרוֹפִּית צִדִּית (ALS)? מחלה זו, המכונה גם מחלת לוּ גֶּרִיג, מובילה להיחלשות...

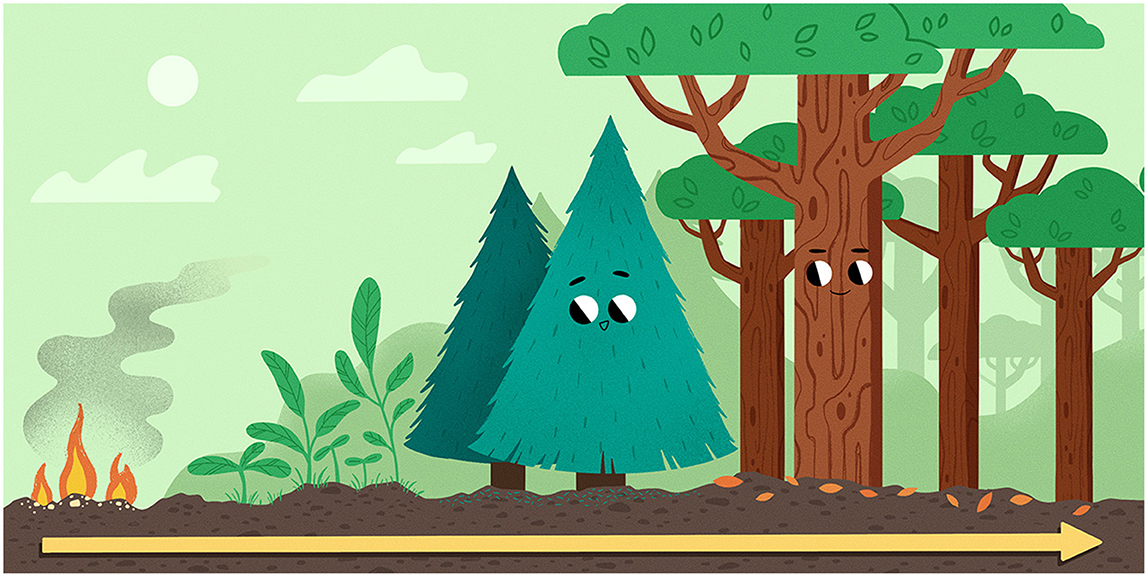

בעונת הקַּיץ, הטלוויזיה והעיתונים מציגים לעיתים קרובות מראות מרשימים של שְׂרֵפוֹת חורש ביערות ים-תיכוניים. בדרך כלל...

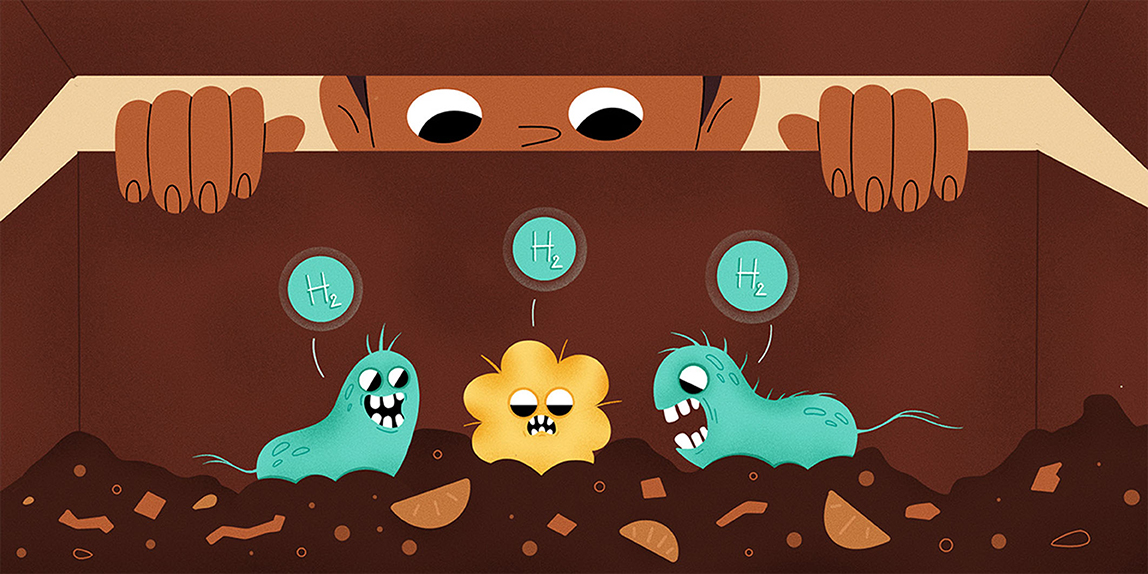

כיצד הייתם מגיבים לוּ היו אומרים לכם כי ישנם מיקרואורגניזמים ’טובים’ שיכולים לאכול זבל? אומנם קיימים מאמרים ודוחות...

כשהמוח בריא, אנו יכולים לזכור דברים; לשים לב; להשתמש בהיגיון; לנוע; לתקשֵׁר; לקבל החלטות ולבצע משימות מורכבות. בעת...