Abstract

Sports coaches encourage us to be active, alert, and to get things done quickly; they also advise us to relax, be patient, and do things slowly. With these changing instructions, we need a system to do things at our own pace. In sport psychology, we call this system goal setting. Goal setting means establishing a target that you want to achieve. When your goals are specific, achievable, and challenging, you feel motivated. Getting a glass of water from the kitchen might be specific and achievable but not challenging, whereas training for the nationals in 3 months’ time might challenge you, but you might not know precisely how or when to train. In this article, we introduce a goal-setting system that can help you to set and achieve the goals that matter most to you.

Goal setting is a process by which people set targets that will help them to achieve desired outcomes, such as winning a swimming competition or learning a new skill. You can imagine goal setting as a map that helps you decide which direction to travel to get to your destination. You are free to choose your own route, but better choices will make the journey easier and allow you to travel with confidence.

Along the way, you may notice that the map does not always accurately describe the territory: some hills seem steeper than the map shows, and some distances take longer to travel. So, you may need to adjust your goals as you go. If you do not choose a direction to travel, then you can wander aimlessly—so it pays to be specific. It is important to know how long the journey will be so that you know how much food to bring. Also, if you are traveling to meet a friend, for instance, your friend would appreciate a time to meet. So, goal setting also requires a timetable and a clear plan [1].

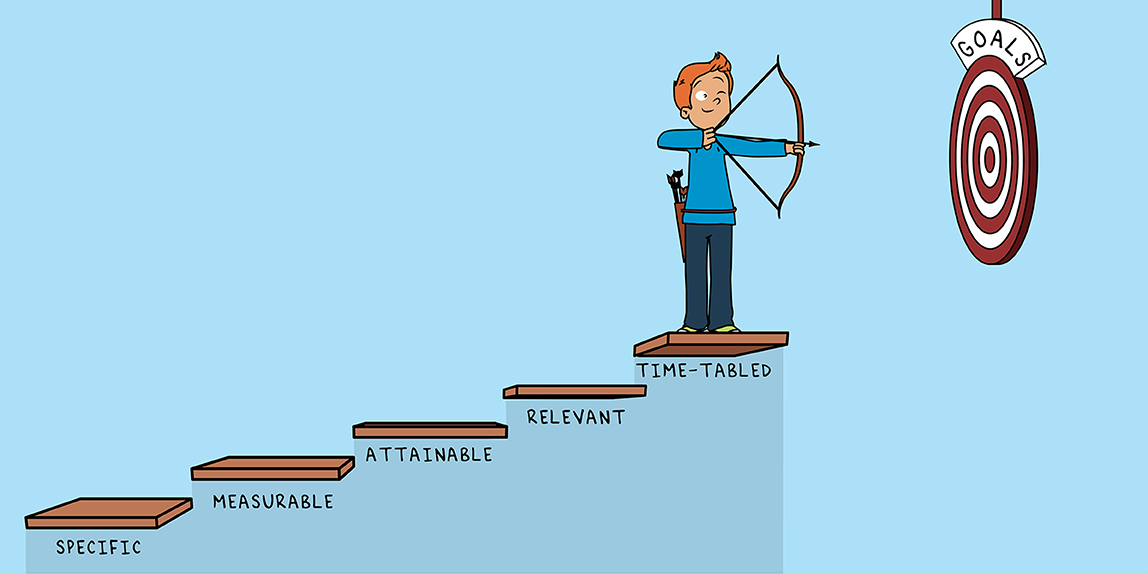

Setting “SMART” Goals

We call the process that we have just described SMART goal setting. In this case, SMART is an acronym for the parts of the process. Whenever you set a goal, you can check it against the SMART criteria: specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-tabled. Specific means that your goal states exactly what you wish to change and improve. Measurable means that you can easily see if you have made progress. Achievable means that your goal is possible to achieve. Realistic means that your goal is challenging but it is within your control to achieve it. Finally, time-tabled means that you set time boundaries around your goal. Goal setting is SMART when everything is flexible and adjusts to your individual needs, the goal being pursued, and your personal environment. If you wish to improve your forehand in tennis, then it does not matter whether you are a professional tennis player or child in a local tennis club; setting goals gives you a helpful target that you can translate into daily actions to follow. The SMART technique works for individuals with different personalities and cultural backgrounds [2]. SMART goal setting provides a formula for achieving the goals that are important to you, using the strengths you already have!

Goal setting is a game with two halves: the first half is to set a goal; the second half is to achieve it. In the game of goal setting, much of what happens in the second half depends upon the thinking and planning that occurs in the first half. To set goals, you often must think about the past as a guide to your future. Unfortunately, people can become prisoners of their stories, which can prevent them from achieving their goals. We might tell ourselves stories like, “It is impossible for me to succeed—I do not have the skills;” or, “Children who live where I live do not become professional athletes.” We carry these stories with us through our lives, but they are often untrue. For example, you cannot be certain that becoming a professional athlete is not possible for you. You might be the one person from your community who becomes a professional athlete, but you would never realize this possibility unless you kept moving toward your goal each day. The mental endurance to keep progressing toward a goal is often what separates athletes who succeed from athletes who do not. The SMART technique works for individuals with different personalities and cultural backgrounds [2]. It is a technique which gives a formula for getting the goals which are important to you, using the strengths you already have.

How to Set Goals

There are three common types of goals that we can set: outcome, performance, and process goals. Outcome goals focus on the results [3]. You might set a goal to win a competition or to get the number 1 rank in your sport, for example. It is important to remember that you are only partly in control of outcome goals because another person or team might simply perform better on the day of the competition. Performance goals have to do with improving your own ability, independent of the other competitors or team members. For example, in rugby, the kicker might wish to improve her conversions from 70 to 80%. The rugby kicker is in control of achieving this performance goal because it does not depend upon anyone else. Process goals are the basic practices we have to do in order to improve our overall capacity to play a sport. Coaches and athletes use process goals in practice to improve performance. For example, a golfer might focus on the top back portion of the ball when practicing putting. Out of these three types of goals, we should remember that only process goals are 100% in our control.

Writing down our outcome, performance, and process goals, maybe at the start of each week, is a purposeful way of striving for improvement. Maybe you have a coach who will help you set your weekly goals. For example, you might set a goal to train or practice on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Setting goals can help you focus your attention on the task at hand. The more you practice with the SMART technique, the better you will become at setting, refining and achieving your goals. Many athletes incorporate this healthy habit into their lives. As you work on your goal setting, keep some healthy guidelines in mind. First, your goals should be realistic but moderately difficult. You should feel like you are just out of your comfort zone. Second, choose your own goals. If you choose your goals yourself, you will feel more motivated and committed to them. Third, choose goals that can give you feedback about how well you are doing. For example, if your goal is to master a specific shot in, every time you play the shot gives you feedback on your progress. Fourth, focus on process and performance goals, not on outcome goals. This will help improve your ability as an athlete and spearhead your development. Last, be sure to set time aside to plan your goals beforehand and to periodically review them as you make progress.

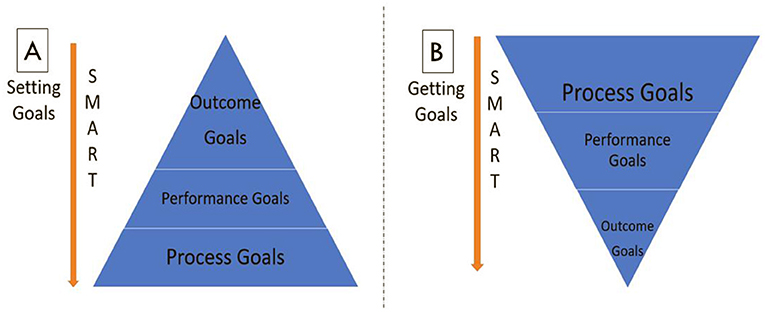

Following a particular order of setting goals and achieving your goals using SMART goal-setting allows us to be consistent and improve. When you are setting goals, you need to look at the short-term, medium-term, or long-term future to decide on your Outcome goal i.e., your destination (e.g., being Junior Number 1 rank). Then you set the Performance goals which are needed to improve your own ability to cross certain milestones to get to your destination i.e., the road you follow (e.g., the tournaments you need to play and the skills you need to master). Lastly, you set your Process Goals which are crucial to building your daily practices and training to keep you on track and follow the road toward your destination (e.g., regular training, nutrition and good support) (see Figure 1A). When you are then getting goals, you start from the other way. You start with process goals which become your vehicle to achieve your performance goals to stay on the road. This eventually allows you to achieve your outcome goals and reach your destination (see Figure 1B). If you do not get your process goals (train regularly, get good support), it is difficult to achieve your performance goals (develop skills and play tournaments), which makes it difficult to achieve your outcome goal (of being Junior Number 1 rank).

- Figure 1 - (A) When setting goals, it is a good idea to start with Outcome Goals, move to Performance Goals, and then finally to Process Goals. This is helpful because it gives you the destination and the path to take.

- (B) When working toward achieving goals, it is helpful to start with working only toward process goals. Achieving process goals automatically puts us on the path to achieve Performance goals, which allows us to eventually achieve our Outcome goals. Figure was designed by Sahen Gupta.

The Road May Be Rough…

When we set goals, we set ourselves up for a future that we hope is within our control. However, because sports are unpredictable, we must keep our minds in a healthy place to manage this uncertainty. Two helpful mechanisms are self-compassion. Self-compassion means not judging ourselves too harshly when things get difficult and instead engage in an understanding and acceptance inward. Self-compassion has enormous benefits for athletes, but unfortunately, not everyone believes this. Some people believe that self-compassion might decrease the drive for self-improvement that characterizes the best performers in any sport—they believe that self-compassion makes athletes lazy! But research suggests that people take more, not less, responsibility when they have self-compassion after a negative event [4]. For example, if you fail to win a tournament, being self-compassionate allows you to understand the reasons why you lost, and positively motivate you to improve those areas.

Striving for perfection helps athletes to achieve excellence in any sport. Healthy perfectionism involves high personal standards—trying to be the best you can be. But perfectionism can have a downside, too. If you set unrealistic goals for yourself and are harshly self-critical when you do not meet them, this is not healthy or helpful for your performance or success. It is important for athletes to regularly ask themselves, “Has my striving for perfection gone too far in the wrong direction?” Balancing perfectionism with self-compassion is the healthiest strategy [5].

Remember, it is common to face difficulties while working toward your goals. For example, research has shown that even elite athletes who practice goal setting found it difficult during the COVID-19 pandemic [6]. From our work with elite athletes, we recommend the ICE strategy to help stick with your goals. “I” stands for identifying goals that mean a lot to you. “C” is for committing to chase your goals despite difficulties. “E” is for expanding your abilities, by learning from the successes and failures of the SMART goal-setting process.

Conclusion

In summary, we set goals to get goals! When you follow the SMART goal-setting formula, you increase your chances of achieving your goals. The mistakes you make along the way are the best way of remembering what you have learned [7]. We finish with a few lines from Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s famous poem, “The Winds of Fate”:

“One ship drives East and another drives West,

With the self-same winds that blow,

‘Tis the set of the sails,

And not the gales,

Which tells us the way to go.”

Glossary

Goal Setting: ↑ The development of an action plan that guides an individual toward a goal.

Outcome Goals: ↑ Outcome goals focus on the end point or the desired end-result in the short or long-term.

Performance Goals: ↑ Performance goals are focused on trying to develop and achieve a better sporting ability.

Process Goals: ↑ Process goals are focused on the day-to-day behaviors one needs to engage in to improve their skills.

Self-compassion: ↑ Being nice to ourselves when we are in pain or face personal shortcomings, rather than hurting ourselves with extra self-criticism.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Jeong, Y. H., Healy, L. C., and McEwan, D. 2021. The application of goal setting theory to goal setting interventions in sport: a systematic review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 17:1–26. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2021.1901298

[2] ↑ Erez, M. 2013. “Cross-cultural issues in goal setting,” in New Developments in Goal Setting and Task Performance eds Edwin A. Locke and Gary P. Latham (New York, NY: Routledge). p. 533–44.

[3] ↑ Weinberg, R. 2010. Making goals effective: a primer for coaches. J. Sport Psychol. Act. 1:57–65. doi: 10.1080/21520704.2010.513411

[4] ↑ Neff, K. 2003. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Ident. 2:85–101. doi: 10.1080/15298860309032

[5] ↑ Breines, J. G., and Chen, S. 2012. Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38:1133–43. doi: 10.1177/0146167212445599

[6] ↑ Gupta, S., and McCarthy, P. J. 2021. Sporting resilience during COVID-19: what is the nature of this adversity and how are competitive elite athletes adapting? Front. Psychol. 12:611261. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.611261

[7] ↑ Metcalfe, J. 2017. Learning from errors. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 68:465–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-044022