Abstract

Off the coast of Vietnam, two recent events seem to have contributed to the death of coral reefs: the rapid invasion of a small marine snail called Drupella, and the emergence of a disease that spreads over corals. We decided to investigate whether there is a link between the corals, the snails, and the disease. We analyzed the mucus covering the surface of corals, both in healthy corals and those infested by Drupella snails. Mucus produced by corals is usually full of helpful microbes, protecting the corals from harmful microbes that can make them ill or kill them. Our analyses showed that, when Drupella eats corals, the snail also removes one of the corals’ primary defenses by eliminating most of the tiny protectors in their mucus. This allows harmful microbes to cause additional damage to the corals.

No Escape for Corals

To protect themselves from attacks by predators, animals like gazelles, rabbits, or mice can run away. For these animals, running is possible because they are mobile. However, other animals are either unable to move or can only move very slowly, over small distances. This is the case for corals. Corals are minuscule animals that live together in rock structures that they build. The rock structures form the coral reefs known for their beauty and for providing shelter for thousands of marine species, including fish, sponges, crustacean, and worms. Sadly, coral reefs are also known for their fragility and the threats that plague them: warming water, predation, hurricanes, damage from human hands and diving fins, and pollution, to name but a few. In addition to their inability to run away from threats, corals naturally grow very slowly—just a few millimeters per year. Today, one-third of coral species are endangered and may disappear in the near future.

The Snail Attack

Some fish and starfish species are famous for feeding on corals, but recently a small marine snail called Drupella, native to the Indian and Pacific oceans, was also discovered to be an active coral predator. In some parts of the world, these slow-moving killers are increasing in number and their attacks sometimes kill the corals.

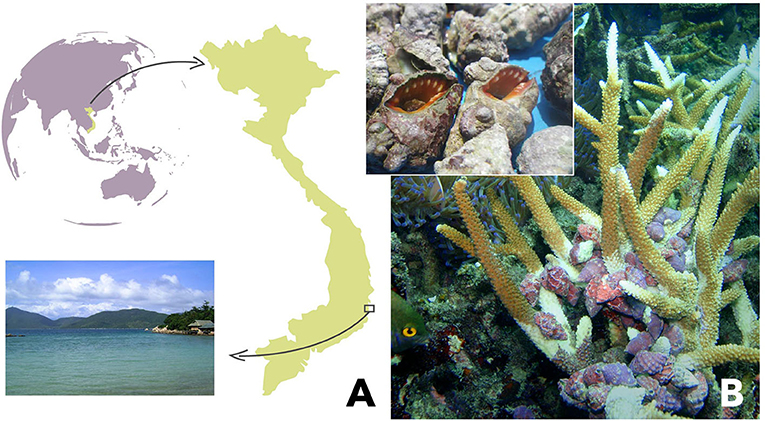

Our research team went to the Bay of Nha Trang in Vietnam. There, the corals are suffering from the growing population of Drupella. In small numbers, this snail does not do much damage, but in recent years the snail population has greatly increased. Corals colonized by snails show two interesting characteristics. First, the corals are left totally white and lifeless after the snails are done with them. Second, traces of coral disease are also visible on the parts of the corals the snails have not yet touched (Figure 1). The aim of our research was to learn more about the links between the snails and the diseases that devastate the corals in Nha Trang. We wanted to see whether Drupella caused disease or whether the corals were already sick before the snails’ arrival. So, we decided to dive in to take a closer look at the corals.

- Figure 1 - (A) The Bay of Nha Trang in Vietnam, where our study took place.

- (B) Drupella eating corals: some parts of the corals are already white, corresponding to the grazed surface. The close-up shows different individuals of Drupella rugosa (© ConserveMarine, CC BY-SA 4.0).

Coral Mucus, a Protective Layer Full of Helpful Microbes

Our first step was to understand the origin of the coral disease. Since corals are unable to move, they are particularly vulnerable to attack by predators. However, they do have defenses against microbial invaders, and not all microbes are dangerous for corals. On the contrary, some microbes help corals stay healthy and are considered to be a component of the corals’ immune system! It is in the corals’ mucus layer that the battle between helpful and harmful microbes plays out. Mucus is a thick, sticky substance that completely covers corals and is produced by the coral itself. This mucus layer contains many helpful microbes that act like soldiers, eliminating any other harmful microscopic intruder that tries to make the corals sick. In our study, we wanted to understand how these tiny soldiers would react during a snail attack. So, we collected the mucus from different parts of corals with and without Drupella, to compare them.

Examining Microbes in the Coral Mucus

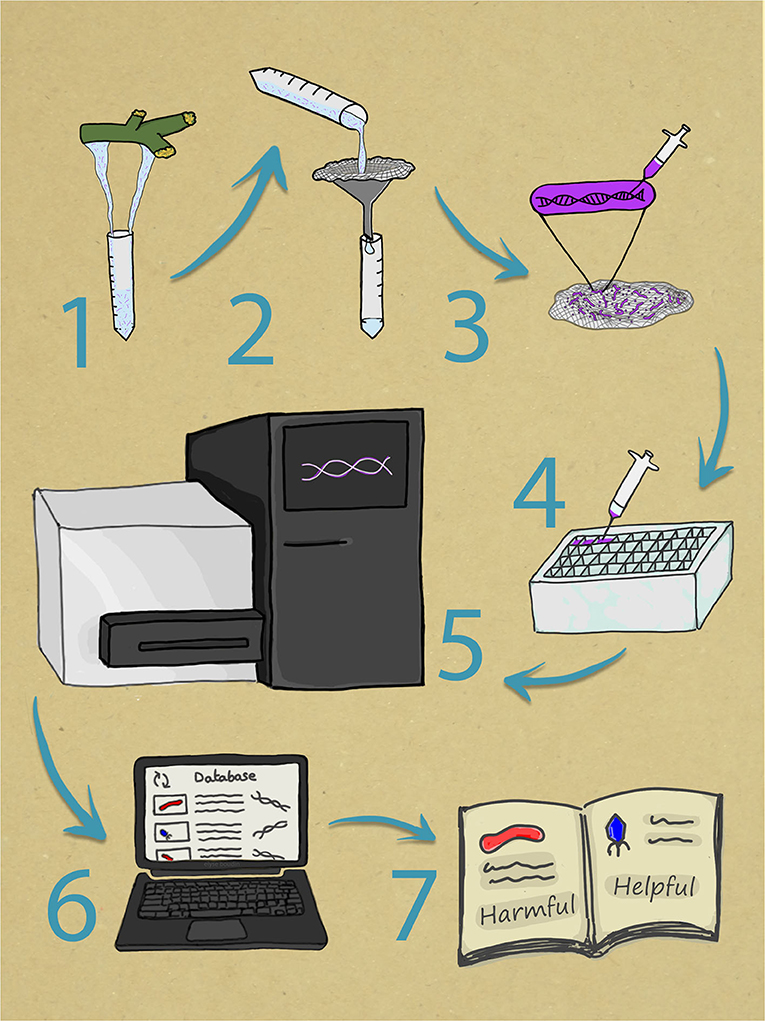

Bacteria and viruses are incredibly small. To give you a sense of scale, bacteria are 100 times smaller than the width of a single hair and viruses are more than 10 times smaller than bacteria! It is therefore impossible to see such small organisms with the naked eye. To detect and identify them, we use DNA sequencing. DNA is found in the cells of all living organisms. It contains the genetic code of the organism and determines all the features of that organism. Imagine an instruction manual with an alphabet of only 4 different letters! The difference between the instruction manual of a human and that of a goldfish is just a matter of the order of some of those letters. Each species’ instruction manual (their DNA) is unique. We extracted as much DNA as possible from the coral mucus, to identify all the microbes living there. Then we searched a database in which the DNA codes of all known living species are referenced (Figure 2), to find the identities of the species we discovered in the coral mucus.

- Figure 2 - Identifying microbes living in coral mucus.

- (1) Mucus is taken from healthy and snail-eaten corals. (2) Mucus is filtered to collect all the microbes. (3) DNA is extracted from the microbes. (4) The microbial DNA is placed in small boxes. (5) A sequencing machine reads and determines the sequences of the DNA in the samples. (6) A computer analyses the data and compares it to a database with the DNA sequences of all known microbes. (7) This tells us which microbes, both helpful and harmful, are present in the mucus (©Elyse Boudin).

Snails Damage Coral Mucus

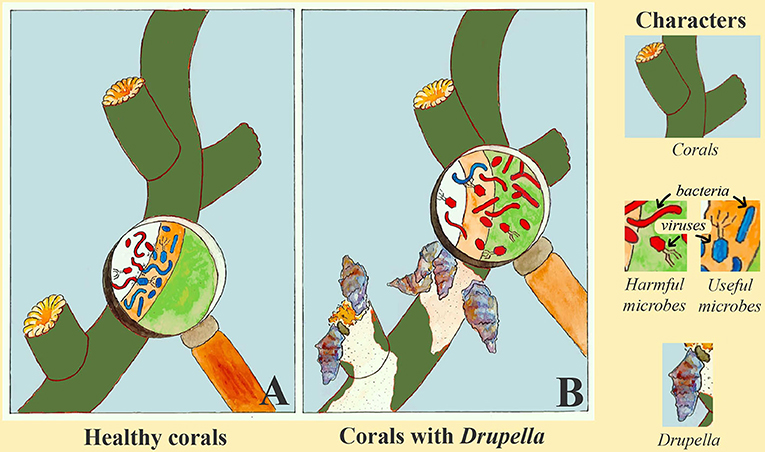

We found that the mucus of corals colonized by Drupella was different from the mucus of healthy corals. The bacteria and viruses found in the snail-colonized coral mucus were different than those found in healthy corals that were spared by the snails, and there were many more of them. Sadly, many of the helpful microbes were also replaced by harmful microbes that are typically responsible for coral diseases (Figure 3). Why are the dangerous microbes growing on the corals that were attacked by snails? Are the snails responsible for this? We believe that the snails, while eating the corals, also seriously damage the corals’ mucus layer and the helpful microbes living in it. If these helpful microbes are no longer able to protect the corals against harmful microbes, then the corals can come under the control of those harmful microbes and become sick.

- Figure 3 - Comparison of corals with and without Drupella.

- (A) The magnifying glass shows us that healthy corals host helpful microbes (blue) in their mucus, which protect them against harmful ones (red). (B) When the mucus layer is damaged by Drupella, more harmful microbes grow, which results in the development of coral diseases (©Jean Péronnin).

Moral of the Story

The “hungry” snail Drupella is naturally present in the seas of Southeast Asia and its population has increased enormously in recent years. The reason for this increase is believed to be overfishing, because the larvae of Drupella snails are normally eaten by fish. Overfishing reduces the number of fish, meaning that more Drupella larvae survive and become adults. Adult Drupella have hard shells and are totally inedible, so they can safely grow and multiply. So, you can clearly see that overfishing has consequences on coral health! We found that not only do the snails scrape the surface of corals and damage them, but snail attack also makes fragile corals even more vulnerable, by providing a path for the invasion of harmful bacteria and viruses.

Finally, our original study [1] shows the importance of both the coral mucus and the helpful bacteria living there that serve as part of the corals’ immune system. Microscopic organisms are being studied by more and more groups, as they are found everywhere in marine animals: in their guts, on their skin, and even in their brains! These helpful microbes have many positive effects on their hosts. This also holds true for humans. The microbes that live on and inside our bodies play important roles in our health, our food digestion, and even in our behavior. Those microbes seem to act as an extremely organized community. However, helpful microbes are so abundant and diverse that we still do not know what they all do. Therefore, we need to continue to research the roles of helpful microbes in all species, since they could reveal other hidden secrets that would help us protect the health of all organisms, from fragile corals to humans.

Glossary

Coral Disease: ↑ Several diseases can affect corals and cause whitening of their surfaces or the formation of white, black, or brown bands on the corals. Coral diseases are mostly caused by bacteria, viruses, or small fungi, and can sometimes lead to coral death.

Microbe: ↑ An organism so small that it cannot be seen with the naked eye. Microbes, which include bacteria and viruses, are the most abundant organisms on earth and are found everywhere—in the air, in the water, and associated with all living organisms.

Immune System: ↑ The bodily system that recognizes unfriendly microbes and defends the organism against them.

Mucus: ↑ The viscous layer produced at the skin surface of most marine animals. It contains a large number of useful microbes involved in the protection of the animal against the surrounding microbial invaders.

Viruses: ↑ The smallest microorganisms on earth (ten times smaller than bacteria). Viruses cannot reproduce by themselves. For this, they have to find a host (which could be bacteria, a plant, an animal, a human being…), get inside the host, multiply, and usually get back out. Like bacteria, they are not always harmful and responsible for diseases. On the contrary, most of them actually protect their host against dangerous bacteria!

DNA Sequencing: ↑ Powerful machine, which allows deciphering the genetic information (DNA) contained in each cell.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Bettarel, Y., Halary, S., Auguet, J. C., Mai, C. T., Bui, V. N., Bouvier, T., et al. 2018. Corallivory and the microbial debacle in two branching scleratinians. ISME J. 12:1109–26. doi: 10.1038/s41396-017-0033-5

References

[1] ↑ Bettarel, Y., Halary, S., Auguet, J. C., Mai, C. T., Bui, V. N., Bouvier, T., et al. 2018. Corallivory and the microbial debacle in two branching scleratinians. ISME J. 12:1109–26. doi: 10.1038/s41396-017-0033-5