Abstract

Using language is a skill that allows us to share our ideas and feelings, to learn in school, and to understand the world around us. Unfortunately, using and understanding language is not easy for everyone—especially for people with developmental language disorder (or DLD). DLD is a hidden but very common condition affecting about 1 out of 15 children. DLD has been given different names in the past, which has sometimes made it confusing for professionals to talk about the condition and for children with DLD to get help. Researchers have studied the different factors that may contribute to DLD, the different types of language problems children with DLD might have, and how children with DLD can be helped. It is very important that we raise awareness for DLD so that the condition will become less mysterious and the lives of the many children who have DLD will become easier.

Humans use language to share ideas and feelings as well as to understand the ideas and feelings of other people. Most of us use language every single day without ever stopping to think about it. Now imagine what it would be like to struggle to understand what people are saying to you or to put your thoughts into words. Think about how hard it would be to share stories, to understand what your teacher is asking you to do, or to explain to your friends why you are feeling upset. This is how it might feel if you had a developmental language disorder.

What Is Developmental Language Disorder?

Developmental language disorder, or DLD for short, is a hidden but very common condition that means a child has difficulty using and/or understanding language. Children with DLD have language abilities that fall behind those of other children their age, even though they are often just as smart. Having trouble with language means that children with DLD may have difficulty socializing with their classmates, talking about how they feel, and learning in school [1]. DLD is very common. If your class at school was made up of 28 students, there would be about two students in your class with DLD. It is a life-long condition. Even though DLD is usually first discovered and treated in childhood, it usually does not go away as a child grows up. There are many adults with DLD, too [2].

Why Is It Called Developmental Language Disorder?

Throughout history, language problems in children have been given many different names. For example, these children have been said to have a “specific language impairment,” a “language delay,” or a “language disorder,” among other labels [3]. Because there were so many different labels being used to describe language problems in children, it was really hard for professionals (like doctors, psychologists, and speech-language pathologists) to talk to each other about these problems, because everyone was using different names. The use of multiple terms for the same disorder also meant that it was difficult for researchers to investigate how to help these children. In 2015 and 2016, a group of experts from around the world came together to solve this problem [4, 5].

The experts agreed that the term “language disorder” should be used to describe severe language problems that will most likely not go away. These language problems make it hard for children to communicate or to succeed in school [5]. Many children have a language disorder along with another disability, like Down syndrome or autism spectrum disorder. Other children, however, could have a language disorder without having any other disability. For these children, the experts agreed that the label “developmental language disorder” should be used [5]. Many people have never heard of DLD, even though it is very common, and that is why it is so important that information about the condition is shared.

Why Do Some Children Have DLD?

The answer to this question is very complicated. Although there is a lot of research on DLD, we do not know why some children have it and others do not. DLD is probably the result of a mixture of different factors, including:

- Biology: a child's physical makeup may play a role in whether he or she has DLD. DLD often runs in families, meaning that the genes a child gets from his or her parents may influence whether that child has DLD. The way that a child's brain is made up and how the different parts of the brain talk to each other may also play a role.

- Cognition: every child is different in how he or she learns new information, thinks about that information and uses that information. These processes are called cognition. Some children are fast thinkers, while some are slow. Some children have really good memories, while some do not. These differences in cognition may play a role in whether a child has DLD.

- Environment: the environment that a child grows up in may also play a role in whether that child will have DLD. A child's environment can either increase or decrease the risk of the child having DLD. There are some people who believe that a child will have DLD if his or her parents do not talk to the child enough—this is not true.

There is no recipe of biology, cognition, and environment that guarantees that a child will have DLD or that a child will not have DLD. When a child does have DLD, it is probably the result of different factors interacting with each other [6].

What Kinds of Language Problems Does Someone With DLD Have?

To really understand the kinds of challenges that someone with DLD faces, it is important to know that language is very complex and that there are many different ways that language can be impaired. A child with DLD will have a very unique profile, meaning that he or she will face a unique set of language challenges. This profile may look very different from other children with DLD and the profile may change as the child gets older. Even though every child with DLD is unique, there are some language problems that are very common among children with DLD.

- Many children with DLD have trouble using proper grammar. For example, a child with DLD might say the sentence, “he play outside yesterday,” instead of “he played outside yesterday.” In this sentence, the child has not added the -ed to the end of the word play to show that it occurred in the past. A child with DLD might say “I walking to school,” instead of “I am walking to school.” In this sentence, the child has not included the form of the verb “to be” that fits in this sentence [7]. Grammar errors, like these examples, are very common for children with DLD.

- Many children with DLD have trouble with sounds. This type of difficulty is especially common when children are very young. There are many different ways that a child may have trouble with the sounds in words when he or she is speaking. For example, children with DLD might leave sounds out (saying “nana” instead of “banana”). Children with DLD might also use the wrong sounds in certain words (saying “wed” instead of “red”).

- Many children with DLD know fewer words than other children their age. The number of words you know is called your vocabulary. Problems with vocabulary will look different as a child grows up. Very young children with DLD may say their first words later than other children. It may also take children with DLD longer to learn and remember new words. Even if a child with DLD has learned a word, it may be hard for him or her to remember that word when talking. This problem is called word-finding difficulty. As children with DLD get older, they may not properly learn that some words have more than one meaning (like the word “cold,” which can mean a low temperature, a sickness, or being unfriendly [6]).

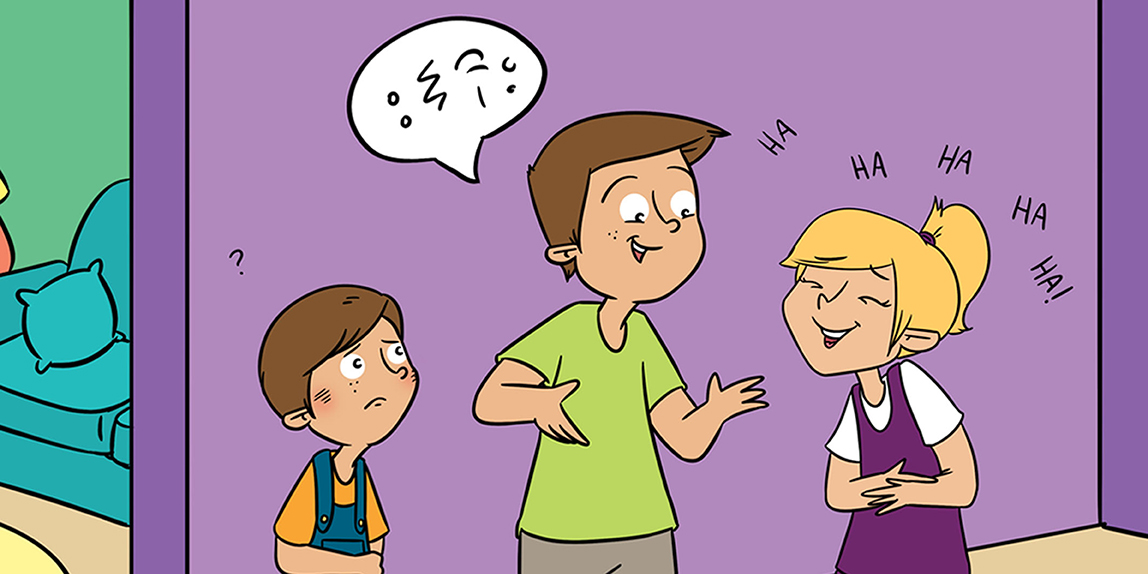

- Many children with DLD have problems properly using language in social situations. Children with DLD might have trouble staying on topic, taking turns in a conversation, or understanding long sentences. These children may have trouble sharing information and telling stories [8]. It might be hard for children with DLD to use words to talk about how they are feeling. This difficulty with making people understand a problem they are having can make children with DLD feel frustrated or angry, and act in ways they are not supposed to.

Although these language problems are common in children with DLD it is very important to remember that no two children have the same language skills, communication, or learning abilities.

How Does A Child With DLD Get Help?

It is very important to know that support from professionals, like speech-language pathologists and teachers, can make a huge difference in the lives of children with DLD. The first step in getting help for a child with DLD happens when someone recognizes that there is a problem. DLD will look different in different children. However, we also know that there are some DLD warning signs that parents and teachers should remember. One DLD warning sign is when a child has problems in school. Language is important for every single subject, so a child with DLD may struggle to understand what he or she is learning, might feel frustrated at school, and might get bad grades. Another DLD warning sign is when a child has language skills that are less advanced than other children the same age. There is a large amount of evidence showing that providing help, also called intervention, for children with DLD can be very effective and can improve that child's language skills. Although many children with DLD will always have language skills that fall behind their peers, getting help can maximize a child's communication and learning potential [1]. By creating greater awareness about DLD, the condition will become less mysterious and children will be helped sooner. We all have a responsibility to share what we know about DLD so that researchers and professionals can continue to work hard every day to help make the lives of children with DLD easier.

Addendum

The article, Developmental Language Disorder: The Childhood Condition We Need to Start Talking About, describes the language problems that may be observed in children with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD). The descriptions and examples of language problems in the article primarily focused on standard English. This addendum adds the important point that the common language learning problems observed in DLD will be different for speakers of other languages or other English dialects. An English dialect is a particular form of the English language that a group of people from a specific region or group speak. Some of the common errors that people with DLD make when they are speaking standard English may not be a sign of DLD for someone speaking an English dialect. For example, he play outside yesterday, which was given in the original article as an example of a grammatical error in Standard American English, would be a perfectly grammatical production by a speaker of African American English [9]. It is very important for professionals, like speech-language pathologists, to understand the specific dialects that may be spoken in their communities in order to properly identify DLD.

Glossary

Language: ↑ The use and understanding of spoken words, written words, or sign language to communicate.

Developmental Language Disorder: ↑ A hidden but common condition that causes difficulty using and/or understanding language.

Speech-Language Pathologist: ↑ A professional who assesses and treats patients of all ages who have speech, language, communication or swallowing disorders.

Grammar: ↑ The structure and rules that are followed in a language.

Vocabulary: ↑ The total number of different words that a person knows.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Norbury, C. F., Gooch, D., Wray, C., Baird, G., Charman, T., Simonoff, E., et al. 2016. The impact of nonverbal ability on prevalence and clinical presentation of language disorder: evidence from a population study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 57:1247–57. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12573

[2] ↑ Clegg, J., Hollis, C., Mawhood, L., and Rutter, M. 2005. Developmental language disorders – a follow-up in later adult life. Cognitive, language and psychosocial outcomes. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46:128–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00342.x

[3] ↑ Reilly, S., Tomblin, B., Law, J., Mckean, C., Mensah, F., Morgan, A., et al. 2014. Specific language impairment: a convenient label for whom? Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 49:416–51. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12102

[4] ↑ Bishop, D., Snowling, M., Thompson, P., Greenhalgh, T., and CATALISE Consortium. 2016. CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study. Identifying language impairments in children. PLoS ONE 11:e158753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158753

[5] ↑ Bishop, D., Snowling, M., Thompson, P., Greenhalgh, T., and CATALISE-2 Consortium. 2017. Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: terminology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58:1068–80. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12721

[6] ↑ Paul, R., Norbury, C. F., and Gosse, C. 2018. Language Disorders From Infancy Through Adolescence: Listening, Speaking, Reading, Writing, and Communicating, 5th Edn. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

[7] ↑ Rice, M., Wexler, K., and Cleave, P. 1995. Specific language impairment as a period of extended optional infinitive. J. Speech Hear. Res. 38:850–63.

[8] ↑ Norbury, C. F., and Bishop, D. 2003. Narrative skills of children with communication impairments. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 38:287–313. doi: 10.1080/136820310000108133

[9] ↑ Bland-Stewart, L. M. (2005) Difference or deficit in speakers of African American English? What every clinician should know…and do. The ASHA Leader, 6, 6–31.