Abstract

Hidden beneath the ocean waves, tiny worms called polychaetes play a big role in keeping ocean ecosystems healthy. Living from sandy shores to deep waters, these colorful, segmented creatures dig tunnels, build tubes, and even swim. As they move through sand and mud, they stir and mix the seafloor, bringing in oxygen, recycling nutrients, and helping other creatures survive. This process, called bioturbation, makes the ocean floor a lively place full of life. Polychaetes also act like “alarms” signaling changes in water quality and pollution—unwanted or harmful substances in the environment, such as trash, chemicals, or oil spills. Though they are small and often unseen, their work is essential for life in the sea. By learning about polychaetes, you will discover that some of the ocean’s most important helpers are tiny creatures working hard below the surface.

The Ocean’s Invisible Engineers

When you think of ocean life, majestic whales, shimmering schools of colorful fish, or serene turtles gliding through the water probably come to mind. These fascinating species have become icons of the ocean and they captivate us—with good reason.

Yet the ocean’s biodiversity extends far beyond these familiar faces. On the seafloor, among grains of sand and layers of mud, an equally fascinating but less familiar story unfolds. It is the story of a group of small, segmented worms who, quietly and without fanfare, help sustain much of the ocean’s functioning. These tiny creatures are known as polychaetes (Figures 1, 2).

- Figure 1 - A striking member of the Amphinomidae family—commonly known as “fire worms”—glides across the seafloor sediments, flaunting its vividly colored and unmistakable body.

- Long, abundant bristles that resemble fine hairs emerge from each segment (Photo credit: Pauline Walsh Jacobson https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/305442038. CC BY 4.0 International).

- Figure 2 - Known as “sea flowers”, sabellids unfurl their delicate crowns of tentacles like a living net, capturing tiny, suspended particles that are then carefully transported toward the mouth—or even used to build or repair the protective tube they call home.

- This elegant strategy helps them feed and find shelter in the underwater world [(Photo credit: Nathan Foster) https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/476829885]. CC BY 4.0 International.

Polychaetes are invertebrate animals, which means they do not have a backbone. Instead of bones, they have soft bodies. Polychaetes belong to the annelid group—animals with long, segmented bodies that look like a chain of connected rings, like earthworms. They inhabit environments ranging from sandy shores to the ocean’s deepest zones, and they have an astonishing diversity of shapes, colors, behaviors, and lifestyles. Some burrow intricate tunnels into the seafloor; others build delicate tubes for shelter; and many swim, hide, or cling to rocks. They can adapt to nearly every corner of the ocean and, while they might look simple at first glance, their role in the ecosystem is extremely important [1]. Many worm species are also a staple in the diets of fish, seabirds, and other animals such as crabs, shrimp, and snails [1, 2].

Masters of Bioturbation

Polychaetes are key players in a process called bioturbation. As they feed, burrow, or move through the sediments of the seafloor, they use their bodies—or parts of them—to mix and aerate the bottom, letting air into places where there usually is not any (Figure 3). This constant motion provides oxygen to the seabed, recycles nutrients, and aids in the breakdown of organic matter. In other words, polychaetes help keep the ocean’s “soil” alive and thriving [1, 2].

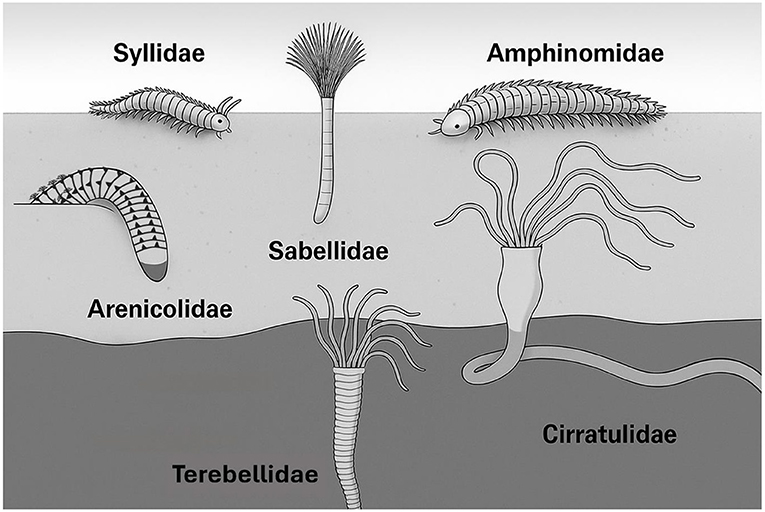

- Figure 3 - Marine polychaetes are an extremely diverse group of organisms with life habits that make them excellent sediment engineers.

- Some move along the surface of the sea floor and others build intricate tunnels underground. They play a crucial role on the seafloor by burrowing, ventilating, and stirring sediments (Figure designed using OpenAI, 2025).

As these worms constantly stir up particles on the seafloor, they reshape the physical structure of the sediment, altering how packed down it is and contributing to the exchange of gases and nutrients with seawater. Their fecal (poop) pellets—sometimes expelled as tiny mounds—can even bury other species or become a food source for other organisms. Collectively, their quiet labor drives the ever-changing processes that shape ocean ecosystems [3, 4].

Sentinels of Change

Beyond their crucial ecological roles, polychaetes are also powerful indicators of ocean health. Their presence or absence, their behaviors, and their abundance can reveal subtle shifts or severe impacts in coastal environments affected by human activities. From pollution (such as wastewater discharged into the sea) to overfishing, these tiny worms “record” what happens around them, becoming true “biological thermometers” of marine ecosystems [5].

A Remarkable Life

The lives of polychaetes are as fascinating as their ecological roles. Their reproduction, for instance, can be either sexual or asexual and is often accompanied by dramatic changes in appearance. To reproduce, some undergo striking body changes that enable them to leave the seafloor and swim up into the ocean’s surface waters, where they release their gametes—special cells (like eggs and sperm) that animals and plants use to make babies—in spectacular swarms synchronized with the phases of the moon. In other species, their bodies literally fragment into one or several parts, which then regrow into new individuals or give rise to clones [1, 6].

Parental Care and Subtle Signals

Some polychaetes display a fascinating behavior known as parental care. They protect their eggs and embryos inside jelly-like capsules, within tubes, or tucked safely beneath their body scales. When their young are ready to be on their own, they use chemical cues in the sediment—produced by bacteria or even by other polychaetes—to locate the perfect spot to continue their development [7].

Small Brains, Complex Behaviors

Despite their seemingly “simple” bodies, polychaetes display an astonishing array of behaviors. Some are active and constantly on the move; others remain firmly attached to the substrate, barely shifting from their spot. As key players in marine food webs, many polychaetes quickly retreat into their tubes or burrows at the first sign of danger, while others master the art of camouflage, blending seamlessly into their surroundings. Remarkably, some can even shed part of their bodies as a defense strategy, distracting predators while they slip away to safety. Certain species harbor toxins in their tissues, whereas others possess an incredibly refined sense of smell, allowing them to detect bait set out by fishermen [8].

Sediment Feeders and Ocean Filterers

The diverse mouth structures of polychaetes mirror the astonishing variety of their diets. Many are sediment feeders—in other words, they “eat mud”—though what they are truly doing is swallowing seafloor particles to extract nutrients hidden within. Others are suspension feeders, capturing drifting particles with tentacles as delicate as they are striking. Some species can even switch between these feeding modes, giving them impressive flexibility to cope with changes in the ocean environment [1]. Each of these strategies reshapes the environment they inhabit, and together, they reinforce the polychaetes’ role as tireless architects of the underwater landscape.

Conclusion: the Art of the Invisible

You might never spot a polychaete while diving, strolling along the beach, or watching an ocean documentary. Yet without them, the seafloor would lose its vitality, nutrients would stop cycling efficiently, and coastal ecosystems would become far more vulnerable to collapse.

Recognizing their value not only deepens our understanding of the ocean but also challenges us to shift our perspective, and to find beauty and purpose in the tiny and unseen. We need to remember that marine life is not made up solely of whales and dolphins—but also by small, invisible engineers who keep it all running behind the scenes.

Glossary

Polychaetes: ↑ Polychaetes are marine worms with many tiny bristles on their bodies. They crawl, swim, or burrow in the ocean and play important roles in marine life.

Annelids: ↑ Annelids are worms with bodies made of many small rings called segments. They live in water or soil and help recycle nutrients in nature.

Bioturbation: ↑ A natural “mixing” of the sand or mud on the ocean floor. Animals like worms dig, eat, and move around, stirring things up and helping keep the seafloor healthy.

Organic Matter: ↑ Bits of plants, animals, or waste that were once alive. In the ocean, it feeds many small creatures and helps recycle nutrients.

Indicator: ↑ Something that gives clues about what is happening in the environment. Certain animals can act as indicators if their presence shows that the water is clean or polluted.

Embryo: ↑ A very young form of an animal or plant that is still developing and growing before it is born or hatches.

Substrate: ↑ The surface or material where plants or animals live or grow. For ocean creatures, the substrate could be sand, rocks, mud, or even other animals’ shells.

Toxin: ↑ A poisonous substance made by animals, plants, or bacteria. Some creatures use toxins to protect themselves from predators.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors declare the use of generative AI for the creation of Figure 3, which is cited as follows: OpenAI. (2025). Grayscale scientific illustration of polychaete families [AI-generated image with ChatGPT]. https://chat.openai.com/.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

[1] ↑ Giangrande, A. 1997. Polychaete reproductive patterns, life cycles and life histories: an overview. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 35:305–83.

[2] ↑ Gimenez, B. C., and Lana, P. 2020. Functional redundancy in polychaete assemblages from a tropical Large Marine Ecosystem (LME). Zoosymposia 19:72–90. doi: 10.11646/zoosymposia.19.1.11

[3] ↑ Hall, S. J. 1994. Physical disturbance and marine benthic communities: life in unconsolidated sediments. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 32:179–239.

[4] ↑ Gérino, M., Stora, G., François-Carcaillet, F., Gilbert, F., Poggiale, J. C., Mermillod-Blondin, F., et al. 2003. Macro-invertebrate functional groups in freshwater and marine sediments: a common mechanistic classification. Vie Milieu. 53:221–31.

[5] ↑ Capa, M., and Hutchings, P. 2021. Annelid diversity: historical overview and future perspectives. Diversity 13:129. doi: 10.3390/d13030129

[6] ↑ Giese, A. C., and Pearse, J. S., eds. 1975. Reproduction of Marine Invertebrates. Vol. III: Annelids and Echiurans. New York, NY: Academic Press, 347. ISBN: 0122825039

[7] ↑ Jamieson, B. G., Rouse, G., and Pleijel, F, eds. 2006. Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Annelida. Enfield, NH: CRC Press, 699. ISBN: 1-57808-313-3.

[8] ↑ Beesley, P. L., Ross, G. J., and Glasby, C. J, eds. 2000. Polychaetes and Allies: The Southern Synthesis, Vol. 4. Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing, 420. ISBN-13, 9780644054836.