Abstract

Have you ever wondered what happens to the leftovers from plants and fruits, like the pulp left after making juice or oil? These leftovers are called biomass, and instead of throwing them away as waste, we can reuse them. Scientists are discovering smart ways to turn biomass into useful things—a process called valorization. This article looks at olive waste biomass, which is the material left after making olive oil. With special tools and processes, olive biomass can be changed into energy to heat homes, fuel for cars and trucks, or ingredients for cosmetics and medicines. By learning the chemistry behind olive biomass you will discover how to reuse it, which protects the environment, and supports local communities. This idea is part of what is called a circular economy, where nothing is wasted and everything gets reused—helping to build a cleaner and better future for everyone.

Why Olive Waste is Not Trash Anymore

Olives and olive oil are enjoyed all over the world. People like their taste and also know their health benefits. You can eat olives as snacks and use olive oil for cooking, salads, or toasts. However, making olive oil generates a lot of leftovers, like pits, pulp (called pomace), and other waste. In the past, these wastes were thrown away. Today, we know that leftover materials from plants, called biomass, is valuable because modern technologies can separate out the useful parts from the waste and turn them into clean energy, fuels, and even cosmetics or medicines. This process is called valorization, which means adding value to waste. Valorizing olive biomass waste protects the environment and creates new jobs and businesses. Valorization is a part of sustainability, which means using resources in a smart way that does not harm the planet.

Biorefineries play a key role in this transformation. These are the industrial facilities where biomass is used to make energy and useful products. Because they come from living things, we call these products “bioproducts” and “bioenergy”. Like with “biomass”, the prefix “bio-” comes from the Greek word “βιo-/bio-”, which means “life”. Using olive biomass in biorefineries supports a circular economy—a system where nothing is wasted. Instead, olive biomass is reused, recycled, or transformed.

This article will explain how olive biomass waste can be turned into valuable bioproducts with the help of engineering, chemistry, and environmental science. Using modern technologies, we can develop bioenergy as an alternative to fuels like gasoline, supporting a cleaner and more sustainable future. To do this well, we must think about the whole life cycle—from where olive waste comes from to how it is used—to make sure we help both people and the planet.

From Olive Waste to Valuable Resources

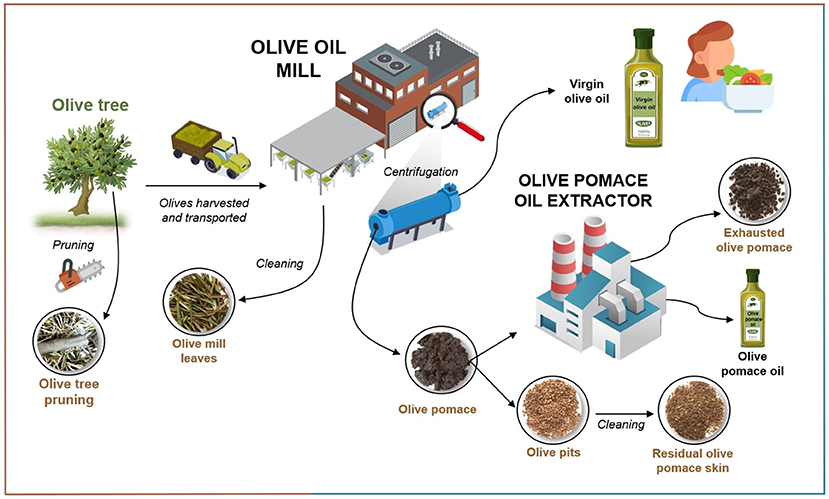

Every year, olive trees are pruned to help them grow new branches, stay healthy, and produce more olives. Trimming the trees creates a type of plant biomass called pruning, which includes branches and leaves. These materials are often burned in the field, which means their potential is usually wasted. After harvesting, olives are cleaned and crushed in a factory called an olive mill to make olive oil. A large machine called a centrifuge—a spinning tool like a washing machine—separates the oil from the rest of the fruit. The remaining fruit is a type of biomass called olive pomace, composed of pulp, peel, water, and pits (also called olive stones). This mix can be separated again to collect the pits and other useful parts (Figure 1).

- Figure 1 - From left to right, this diagram shows how olives are turned into olive oil and the types of olive biomass (shown in black circles) made along the way.

- It also shows which industries are involved, namely the olive oil mill and the olive pomace oil extractor.

Biomass “waste” is actually full of valuable components. Olive biomass has a unique chemical composition and high energy content. For example, olive stones can release a lot of energy when burned, making them an excellent source of renewable energy for heating or generating electricity [1]. Other parts, like pomace and leaves, contain antioxidants used in cosmetics and medicines to protect cells and skin from damage. Other helpful chemicals in olive biomass include mannitol, a sweetener with few calories, and maslinic acid, which is used in skin care and healing [2, 3]. Olive biomass also contains three important plant components: lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose. These materials can be turned into eco-friendly products like green chemicals, new materials, and even bioplastics [4].

Olive Biomass-Based Biorefineries

Olive biomass has great potential for use in biorefineries which, as we explained earlier, are “factories” that transform organic materials like plant waste into clean energy and useful products. Scientists are working hard to find new, planet-friendly ways to do this. There are different methods of turning olive waste into something useful, depending on what causes the change. When heat is used, it is called a thermochemical process. Tiny living things like bacteria or yeast can be used in biochemical processes. Finally, chemicals can be used in chemical processes.

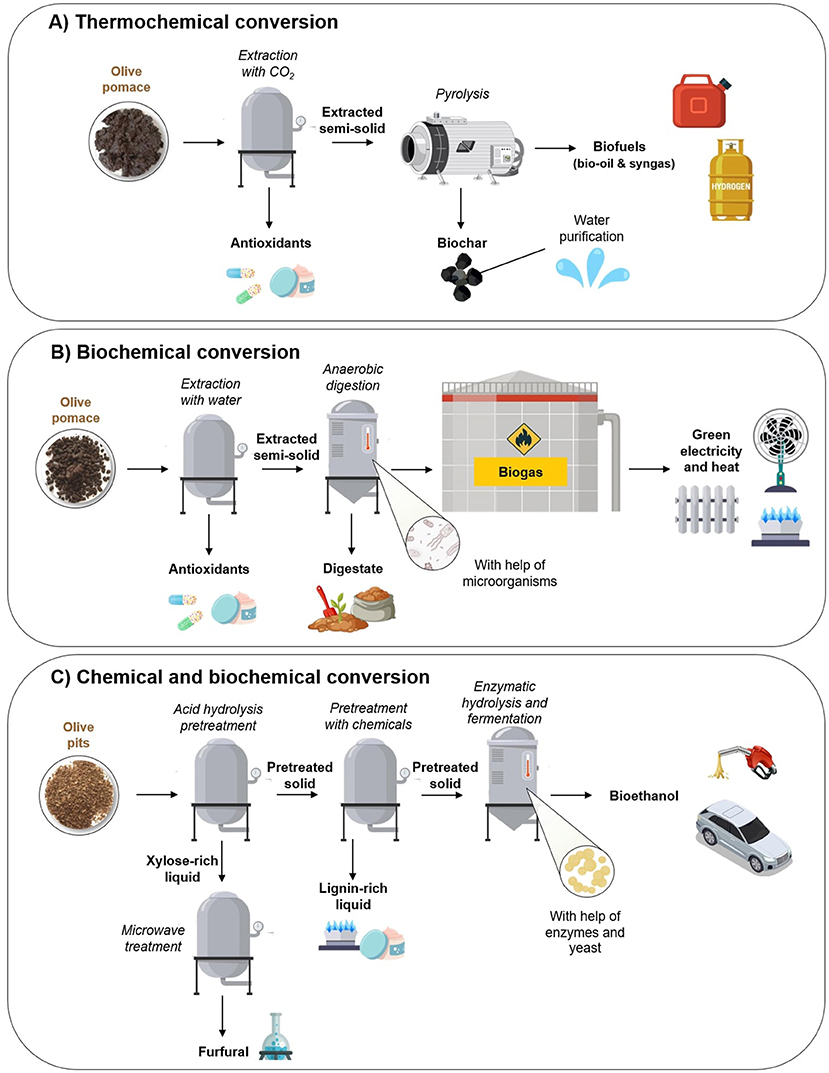

In Figure 2A, scientists use extraction to recover antioxidants. Then they use a thermochemical process called pyrolysis, in which the material is heated to very high temperatures without oxygen. This creates biochar, a type of charcoal that helps clean water or improve soil. This process also makes bio-oil and syngas, two fuels that can be used to produce energy [5].

- Figure 2 - (A) Thermochemical, (B) biochemical, and (C) chemical pathways can be used to turn olive biomass into valuable chemicals, materials, and biofuels.

In Figure 2B, olive pomace is first extracted to obtain antioxidants. Next, microorganisms break down the olive biomass without oxygen, producing biogas, a type of fuel rich in methane (CH4). The solid waste that remains at the end of the digestion is called digestate, and it can be used as natural fertilizer [6].

In Figure 2C, two different processes are used to get useful products from olive pits. First, in a chemical process, pits are treated with acid to obtain a sugar called xylose. Xylose is then turned into a useful chemical called furfural that can be further refined into for example glues or plastics. Leftover solids are used to make bioethanol, a type of biofuel that can replace gasoline. To do this, scientists use enzymes, special proteins that speed up chemical reactions. In Figure 2C, enzymes help convert cellulose into glucose. Then, a common type of yeast called Saccharomyces cerevisiae uses this glucose to grow and release ethanol, which can be used as fuel for transportation [7].

Unlocking the Potential of Olive Biomass

Transforming olive biomass into renewable energy and useful products is a big step toward a sustainable future. However, it is not simple. Olive biomass is produced in many places, takes up a lot of space, and is only available at certain times of the year. This makes collecting, transporting, and preparing it more difficult than using oil or natural gas.

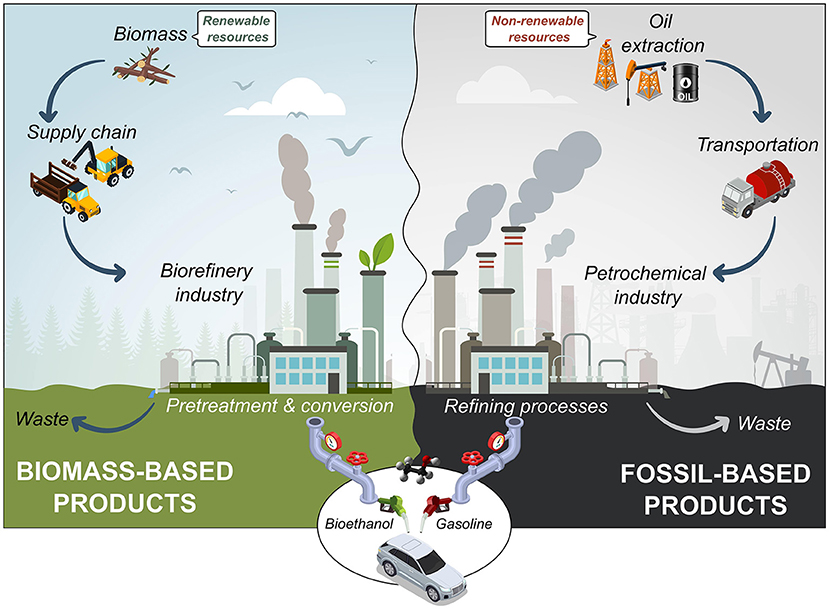

Before it can be used in a biorefinery, olive biomass often needs pretreatment steps like drying and grinding, which add extra energy and costs. If these challenges are not handled well, the benefits of using olive biomass could be lost. To check that these bioproducts are good for the planet, scientists use a tool called a life cycle assessment (LCA), which helps them understand the impact a process has on the environment, from start to finish. LCA looks at each step—from collecting olive biomass to producing and delivering the final product—and calculates the energy used and the pollution created. This helps estimate the overall environmental impact of bio-based products and compared them to fossil ones (Figure 3). For example, substituting 40% of gasoline with bioethanol can lead to a more than 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions associated with climate change [8]. Although fossil fuels and bioenergy both produce emissions and waste, fossil fuels come from non-renewable sources and contribute more to long-term problems like climate change. Since bioenergy comes from biomass, it can be more sustainable when managed responsibly. LCA helps compare both systems fairly, by looking at their full impact. For example, it can show if moving or treating the olive biomass uses so much energy that it cancels out the benefits. This helps us make sure that products like biofuels and green energy are truly better than gasoline or other fossil fuels.

- Figure 3 - A life cycle assessment can compare the environmental impacts of bioethanol made from biomass vs. the impacts of gasoline made from fossil fuels.

- Both production systems use energy and produce emissions and waste. LCA helps us understand the total impact of each step—from raw materials to the final fuel product.

Another important part of this puzzle is organizing the supply chain—which means planning how to move olive biomass from where it is produced to the biorefineries, and how the finished products are sent to consumers who need them. Building biorefineries close to places with lots of olive biomass can save time and money and reduce pollution. It is also important to make sure the right amounts of bioproducts are made at the right times, so people and industries can use them when they need them. To do this, scientists use computer programs that can test different supply chain options, including transport routes, how much biomass is available, and where people live. This helps scientists find the smartest and most eco-friendly ways to manage the supply chain. By combining careful planning, LCA, and smart supply systems, we can unlock the most value from olive biomass and build a cleaner, greener future.

Smart Solutions for a Sustainable Tomorrow

Olive biomass is a valuable resource that can help build a circular economy. It also supports sustainability, taking care of our planet into the future. This is especially important in Mediterranean countries and other regions where olives are grown. There are many ways to turn olive biomass into useful materials, biofuels, and chemicals. Each method can help reduce waste, satisfy people’s needs, and protect the environment. However, to ensure these methods are truly good for the planet, scientists must study them carefully, using lab experiments and special tools like LCA and computer simulations. These approaches help scientists understand the full environmental impact of each option—from beginning to end. By using science to choose the best ways to turn all kinds of biomass into useful products, we can create a better future for both people and the planet!

Glossary

Biomass: ↑ Material that comes from living organisms, such as agricultural waste.

Valorization: ↑ Turning waste into useful and valuable products, like energy, fuel, or chemicals.

Biorefinery: ↑ A system or industrial facility that uses biomass to produce energy, fuels, and other valuable products.

Circular Economy: ↑ A system where things are reused, recycled, or turned into new products instead of being thrown away.

Antioxidants: ↑ Natural substances that protect our cells from damage and are used in foods, cosmetics, and medicine.

Extraction: ↑ The process used to separate specific compounds from a mixture, often by using a liquid (solvent) that dissolves the desired compound.

Pyrolysis: ↑ A process where something is heated without oxygen to break it down and make fuels or other products.

Life Cycle Assessment: ↑ A scientific method to evaluate the environmental impact of a product or process by looking at every stage—from raw material collection to use and disposal.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank projects PID2023-151855OA-I00 and PID2023-149614 OB-C21 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by FEDER, UE. Authors also acknowledge the project TED2021-132614A- I00 by the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR.

AI tool statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT was used to improve writing.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Original Source Article

↑Gómez-Cruz, I., Contreras, M. d. M., Romero, I., and Castro, E. 2024. Towards the integral valorization of olive pomace-derived biomasses through biorefinery strategies. ChemBioEng. Rev. 11:253–77. doi: 10.1002/cben.202300045

References

[1] ↑ Marquina, J., Colinet, M. J., and Pablo-Romero, M. D. P. 2021. The economic value of olive sector biomass for thermal and electrical uses in Andalusia (Spain). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 148:111278. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.111278

[2] ↑ Gómez-Cruz, I., Contreras, M. M., Romero, I., and Castro, E. 2022. Optimization of microwave-assisted water extraction to obtain high value-added compounds from exhausted olive pomace in a biorefinery context. Foods 11:2002. doi: 10.3390/foods11142002

[3] ↑ Ortiz-Arrabal, O., Chato-Astrain, J., Crespo, P. V., Garzón, I., Mesa-García, M. D., Alaminos, M., et al. 2022. Biological effects of maslinic acid on human epithelial cells used in tissue engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 10:876734. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.876734

[4] ↑ Jurado-Contreras, S., Navas-Martos, F. J., Rodríguez-Liébana, J. A., and La Rubia, M. D. 2023. Effect of olive pit reinforcement in polylactic acid biocomposites on environmental degradation. Materials 16:5816.

[5] ↑ Goldfarb, J. L., Buessing, L., Gunn, E., Lever, M., Billias, A., Casoliba, E., et al. 2017. Novel integrated biorefinery for olive mill waste management: utilization of secondary waste for water treatment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5:876–84. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b02202

[6] ↑ Orive, M., Cebrián, M., Amayra, J., Zufia, J., and Bald, C. (2021). Techno-economic assessment of a biorefinery plant for extracted olive pomace valorization. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 147:924–31. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2021.01.012

[7] ↑ Padilla-Rascón, C., Romero-García, J. M., Romero, I., Ruiz, E., and Castro, E. 2023. Multicompound biorefinery based on combined acid/alkaline-oxidative treatment of olive stones. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 169:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2022.11.010

[8] ↑ Bello, S., Galán-Martín, Á., Feijoo, G., Moreira, M. T., and Guillén-Gosálbez, G. (2020). BECCS based on bioethanol from wood residues: potential towards a carbon-negative transport and side-effects. Appl. Energy 279:115884. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115884