Abstract

Imagine your skin as a superhero’s armor. It protects your body, keeps germs out, and even helps you feel the world around you. But what happens when this armor is only as delicate as a butterfly’s wings? That is what life is like for kids with a skin condition called epidermolysis bullosa (EB), where even a small bump or rub can cause painful blisters. This article explains the basic anatomy of your skin, the proteins that “glue” your skin together, and the underlying causes of EB. We explore the four types of EB, how doctors diagnose and treat it, and what daily life is like for kids living with the condition. The goal of this article is to increase awareness and understanding of EB, and to empower people living with “butterfly skin” and those supporting them.

Starting With the Basics—What is Skin Made of?

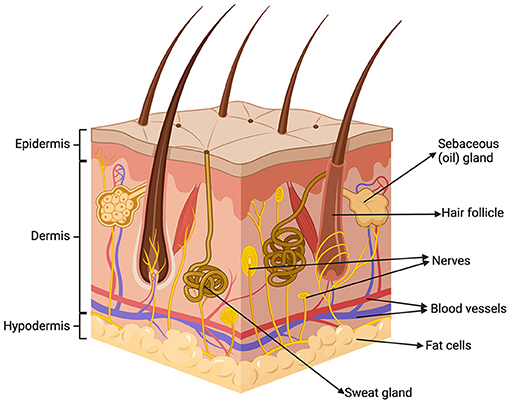

Your skin is incredible! It is the largest organ in your body and has three layers (Figure 1). The top layer is called the epidermis. It protects you from the outside world, such as rays from the sun or germs that can give you infections. The middle layer is called the dermis. It contains important structures like blood vessels, nerves, hair follicles, sweat glands, and oil glands. Finally, the bottom layer is called the hypodermis. It consists of connective tissue and fat cells, which cushion your muscles and bones. These three layers are connected by proteins, which are tiny building blocks in your body. Your skin contains special proteins that act like glue to hold everything in place. Some of these proteins are called keratin, laminin, collagen, and kindlin.

- Figure 1 - Your skin has three layers (from top to bottom): the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis.

- These three layers contain structures like blood vessels, nerves, hair follicles, sweat glands, oil glands, and fat cells.

What is Epidermolysis Bullosa?

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a rare skin disorder that makes the skin incredibly fragile, like butterfly wings. That is why it is often called the “butterfly skin” disease. For someone with EB, even walking or scratching an itch can cause painful blisters or wounds.

You may be surprised to learn that EB is not just one condition; it is actually a group of conditions. Some people with EB might have mild symptoms, like occasional blisters on the hands and feet. Others might have more severe symptoms that affect the skin as well as the inside of the mouth, esophagus (the tube that carries food and liquid from the throat to the stomach), and other body parts.

What Causes EB?

To understand what causes EB, you can think of your body as a factory. Your genes are the instruction manual for the factory that tell your body how to build important structures. Everyone has thousands of genes that are passed down from their parents. Genes come in pairs, and you get one copy of each gene from each parent—a process called inheritance. Your genes decide lots of things about you, including the color of your eyes, how tall you will grow, and how strong your skin will be.

In EB, there is a mistake in one or more genes responsible for creating the special proteins that hold the layers of skin together. These mistakes, called mutations, can cause the proteins to be made incorrectly or stop them from being made altogether. There are over 1,000 mutations that can cause EB [1]. When the skin layers do not stick together properly, they can slide apart with the tiniest bump or rub. When the skin slides apart, the body fills the space with fluid, creating a blister. After the blister pops, an open wound may develop.

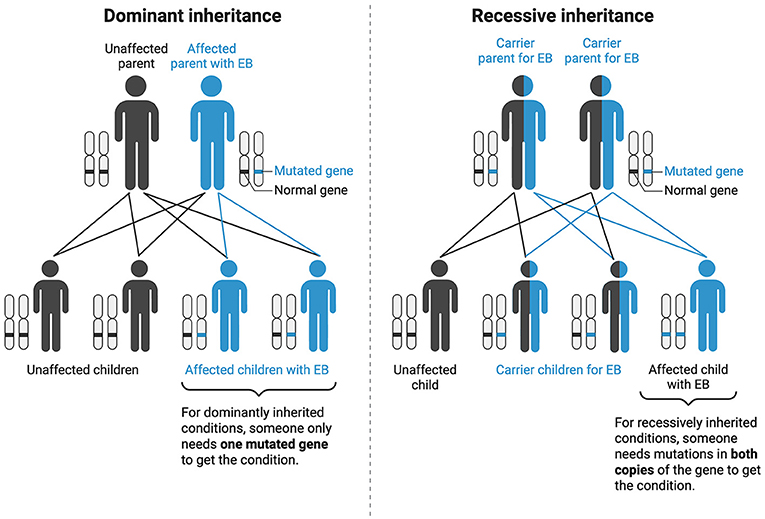

There are two ways to inherit EB: dominantly or recessively (Figure 2). Dominant inheritance means that someone only needs one copy of a gene with a mistake to have EB. Recessive inheritance means that someone needs mistakes in both copies of the gene (one from each parent) to have EB. Understanding how EB is inherited can help doctors and scientists develop new treatments.

- Figure 2 - Inheritance explains how conditions like EB are passed down from parents to their children.

- Dominant inheritance means that someone only needs one copy of a gene with a mistake (“mutation”) to have EB. Recessive inheritance means that someone needs mistakes in both copies of the gene (one from each parent) to have EB. In recessive inheritance, if someone only has one gene with the mutation for EB, they become a “carrier” for the condition. This means that someone has (“carries”) a mutated gene but does not have the condition. However, carriers can still pass the mutated gene on to their children!

The Four Main Types of EB

There are four main types of EB, depending on which layer of the skin is abnormal.

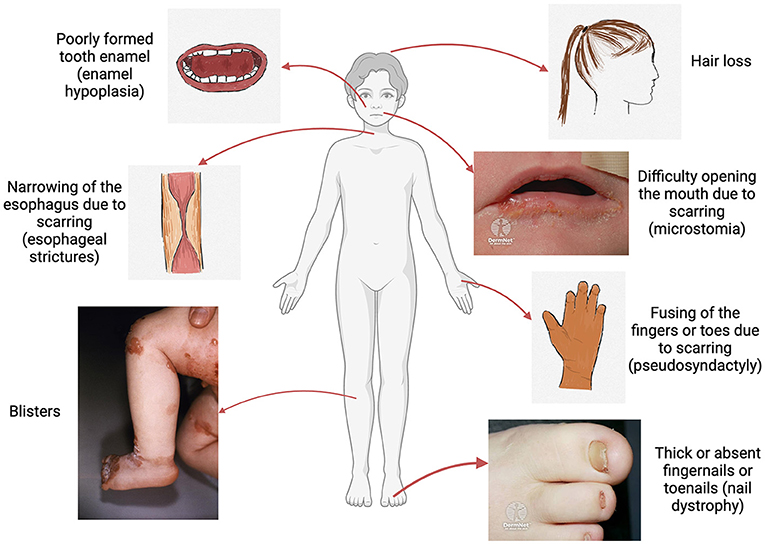

The first type is called epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS). EBS affects the epidermis (top layer). It is usually caused by mistakes in the genes that make keratin proteins, which form networks to strengthen the epidermis [2]. People with EBS can have blisters all over the body, or just on areas that rub against surfaces a lot, like the hands and feet (Figure 3). Blisters tend to heal without leaving scars.

- Figure 3 - Common symptoms experienced by people living with EB include blisters, hair loss, poorly formed tooth enamel (enamel hypoplasia), difficulties opening the mouth due to scarring (microstomia), narrowing of the esophagus due to scarring (esophageal strictures), thick or absent fingernails or toenails (nail dystrophy), and fusing of the fingers or toes due to scarring (pseudosyndactyly).

- (Images sourced from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Image Library and DermNet NZ under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 (New Zealand) license. See DermNet NZ images at: DermNet NZ – Epidermolysis Bullosa).

The next type is called junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB). In JEB, the problem happens at the “junction” where the epidermis (top layer) and dermis (middle layer) meet. It is commonly caused by mistakes in the genes that make laminin proteins, which serve as anchors [3]. This type can lead to blisters on the skin and inside the body, like in the mouth and throat. Babies with JEB might have fragile skin when they are born. When blisters develop inside the body, such as in the mouth and throat, people can have difficulty eating or breathing and voice changes (Figure 3).

The third type is called dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB). DEB affects the deeper layers of skin. It is caused by mistakes in the gene that makes a collagen protein, which acts like a strong rope to tie the skin layers together [3]. Blisters from DEB do cause scarring. In some cases, the fingers or toes may fuse together over time due to repeated scarring, which is called pseudosyndactyly (Figure 3).

Finally, the fourth type is called Kindler syndrome. Kindler syndrome is the rarest kind of EB. It is unique because it can affect all layers of the skin, not just one. It is caused by mistakes in the gene that makes the kindlin protein, which helps skin cells attach to each other [3]. In addition to blisters, people with Kindler syndrome may notice their skin is sensitive to sunlight and gets thinner as they get older.

How do Doctors Diagnose EB?

Doctors can figure out if someone has EB using several methods. The first way is by looking at the skin during a medical visit. If someone has blisters or wounds that are not healing, a doctor may suspect EB. Doctors may also do a procedure called a skin biopsy. This is when they take a tiny sample of skin to look at under a microscope to see which part of the skin is not working properly. The best test for EB is genetic testing, which is when doctors take a small sample of your body’s cells (usually a small amount of saliva) to look closely at your genes. Scientists take the sample to a special laboratory and use a machine to read through your genes to look for any mistakes. If they find a mistake, this can explain why someone has EB, what type of EB they have, and what treatment may work best.

How is EB Treated?

Right now, there is no cure for EB, but there are ways to manage the condition. People with EB typically use special bandages that protect the skin and help it heal, serving as another layer of armor. These bandages are soft and do not stick to the skin, but they must be changed regularly to keep the skin clean and healthy. For some people, dressing changes can take several hours. EB can be a very uncomfortable condition, and doctors may give medicines or creams to ease the itching and pain caused by blisters and wounds. Kids with EB have trouble eating because of blisters in their mouths and narrowing of their esophagus. They may have to get a feeding tube that goes directly into their stomach to help them get the nutrients they need.

While there may not be a cure for EB yet, scientists are working on finding new treatments and hopefully one day a cure. Remember how EB is caused by a mistake in the genes? There are new kinds of treatments called gene therapies that work by delivering a healthy copy of the faulty gene directly into skin cells [4]. There is also a special gel made from birch bark that can help wounds heal faster [5].

How Does EB Affect Children Who have it?

Kids with EB are just like you—they love to play and make friends! But because of their fragile skin, sometimes they must be more careful with certain activities. Some sports and games, like running or football, can be tough for kids with EB who are prone to getting blisters on their feet. But they can still participate and have fun! They may require modifications during the game or the next day after they have developed blisters. Or they might prefer other fun activities like dancing and drawing. Kids with EB may have a nurse or one-on-one aide to help make school more comfortable for them. They may also use a wheelchair or scooter to get around and take breaks during the day to change their bandages. To protect their skin, they may turn their clothes inside out or avoid wearing zippers and buttons that can rub against their skin. Some kids with EB may consume special nutrition drinks to help them stay healthy and strong. People with EB can be more sensitive to hot weather, and they may need a personal fan or prefer to play indoors during recess if the weather is too hot. Because there are so many different types of EB, every person is affected differently. Some people with EB can even play on a football team without a problem!

What Should I Keep in Mind if i Have a Friend With EB?

If you know someone with EB, the most important thing is to be kind and understanding. Remember that someone with EB might look or do things differently than you, but they are the same on the inside. They like to laugh, learn, and be included in games and activities. If you are not sure what your friend with EB can or cannot do, just ask! They will appreciate that you are thinking of them and want to include them. If you hear someone making unkind comments about your friend’s bandages or skin, stand up for them! A common misconception is that EB may be contagious—but as you have learned, it definitely is not! By learning more about EB, you can help make the world a more understanding and inclusive place for everyone, no matter how delicate their skin might be.

Glossary

Keratin: ↑ Skin protein that acts as a support structure for skin cells and forms strong networks in the epidermis (top layer).

Laminin: ↑ Skin protein that anchors the epidermis (top layer) and dermis (middle layer) together and contributes to wound healing.

Collagen: ↑ Skin protein that keeps the skin stretchy but tough, and acts like a strong rope to tie the epidermis (top layer) to the dermis (middle layer).

Kindlin: ↑ Skin protein that helps skin cells work together to stay attached, grow, and migrate.

Dominant Inheritance: ↑ A child needs a mistake in only one copy of the gene (from either the mother or the father) to have a trait or condition.

Recessive Inheritance: ↑ A child needs mistakes in both copies of the gene (from both the mother and the father) to have a trait or condition.

Genetic Testing: ↑ Test that takes a small sample of your body’s cells (usually saliva) to look closely for any mistakes in your genes that can cause diseases.

Gene Therapy: ↑ New kind of treatment that tries to fix a gene with a mistake or replace the faulty gene with a healthy gene inside your cells.

Conflict of Interest

Diana Reusch is an investigator for Abeona Therapeutics, Castle Creek Biosciences, and Krystal Biotech. She has received grants from EB Research Partnership and Child’s Play Charity. She has been a consultant for Chiesi USA and Sun Pharma. She has ownership of Merck, Cigna, and Organon.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

All figures were created with https://www.BioRender.com.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

[1] ↑ Sánchez-Jimeno, C., Escámez, M. J., Ayuso, C., Trujillo-Tiebas, M. J., and del Río, M. 2018. Genetic diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa: recommendations from an expert Spanish Research Group. Actas Dermosifiliogr. (Engl. Ed.). 109, 104–22. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2017.12.005

[2] ↑ Sprecher, E. 2010. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Dermatol. Clin. 28, 23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2009.10.003

[3] ↑ Bardhan, A., Bruckner-Tuderman, L., Chapple, I. L. C., Fine, J. D., Harper, N., Has, C., et al. (2020). Epidermolysis bullosa. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 6, 78. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0210-0

[4] ↑ Guide, S. V., Gonzalez, M. E., Bagci, I. S., Agostini, B., Chen, H., Feeney, G., et al. 2022. Trial of Beremagene Geperpavec (B-VEC) for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 2211–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206663

[5] ↑ Kern, J. S., Sprecher, E., Fernandez, M. F., Schauer, F., Bodemer, C., Cunningham, T., et al. (2023). Efficacy and safety of Oleogel-S10 (birch triterpenes) for epidermolysis bullosa: results from the phase III randomized double-blind phase of the EASE study. Br. J. Dermatol. 188, 12–21. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljac001