Abstract

Sometimes, children cannot live at home because their parents cannot care for them or someone at home is not treating them well. When this happens, they may move to a children’s home—a place where they live with other children and are cared for by adults. But how do children feel living in these places? In the HERO study, we asked 264 kids living in children’s homes about their feelings and their lives. Many said they often feel sad or worried, but not all were unhappy. Many show resilience, the strength to cope and still find joy when things are hard. We found that children feel better when adults listen and take their thoughts seriously. Stress from school also affects feelings, so extra support like tutoring or caring teachers might help. Our study helps us understand children’s mental health and find better ways to help kids feel safe and happy wherever they grow up.

Why do Kids Live in a Children’s Home?

Have you ever stayed at a friend’s house for a night? Now imagine having to live in a new place for a long time, away from your parents. Some kids cannot live with their parents because something at home is not safe or right. Maybe their parents are having big problems and cannot care for them, or someone at home might hurt them. When this happens, special adults, like judges for example, step in to help. These adults might decide that the child needs to stay somewhere safer for a while, such as a children’s home.

In a children’s home, kids live with other children who also had to leave their families. They are cared for by adults, who in some countries are called residential care workers. These adults help keep children safe, care for their needs, and support them while their families work on making things better at home. The goal is to help families improve so children can go back home.

Even though children’s homes are meant to help, living away from family can be hard. Kids in children’s homes often face challenges that can affect how they feel. These challenges can make it harder to be happy and manage emotions [1, 2]. This is part of mental health, which is about how we feel inside—whether we are happy, sad, worried, or something in between. Sometimes, people have big feelings, and that is okay! What matters is having ways to understand those feelings and people who support us. Our study looked at how kids in children’s homes feel, so we can better understand their mental health and help them feel safe, supported, and happy.

What do Children Say About Living Away From Home?

Other researchers have studied how children feel when they live away from home [3, 4]. They found that many children feel sad. Moving away from your family and living in a new place can be really tough. When kids arrive at a children’s home, they do not know the other children or the adults caring for them. Sometimes, they also need to go to a new school. The children’s home might not be in the same village, town, or city where they lived before. The adults try their best to help, but it is not the same as having your own parents around all the time. Different adults help at different times of the day, but they do not live there. They go home after work.

The HERO Study

Most studies ask the adults how children are doing, but we wanted to hear directly from the kids. So, we visited children’s homes and asked children how they feel and what helps them.

We asked 264 children between 11 and 18 years old, living in children’s homes in Luxembourg, how they were feeling and what they thought about their lives. We called our study HERO because children who go through tough times often need special strengths—like superheroes have—to get through hard situations.

We did our study in Luxembourg (a small country in Europe, between Germany, France, and Belgium) because there is not much research about children in care there. A lot of studies about children who live away from their families are done in big countries like the United States or Australia. But children’s homes are not the same everywhere. Countries have different rules and ways of caring for children. We wanted to see if what researchers found in other countries is also true in Luxembourg. What works in one place might not work the same elsewhere. By doing research in Luxembourg, we can learn what life is really like for children there, not just guess based on studies from other countries.

In our study, there were about the same number of girls and boys. Most of the children (around 70%) were born in Luxembourg. Many had to leave their families because their parents could not care for them, because someone at home was not treating them kindly, or because it was not safe there.

How Did We Do The Study?

First, we explained the study to the children and asked if they wanted to take part. It is really important that every child was able to choose for themselves whether to participate. The children who said “yes” filled out a questionnaire to tell us about their lives and how they feel. It was a small booklet with questions, and they answered by ticking boxes. In Luxembourg, children learn to read in German and French at school. That is why we made the questionnaire in both languages, so each child could choose the one they felt most comfortable with. If something was not clear, they could ask for help. The questionnaire was anonymous. We did not ask for names, and we did not know who gave which answers.

What Did We Learn From Kids In Children’s Homes?

Have you ever felt sad or worried? Many kids in our HERO study felt this way too. More than half—about 56%—told us they often feel sad. Almost as many said they worry a lot and often feel scared. We also found that feeling stressed about school or feeling like adults do not listen can really affect how children feel.

Here is something interesting we discovered: even though many children felt sad or scared, not all were unhappy with their lives. In fact, about 23% of the children who often felt sad or scared still said they were happy with their lives overall. This shows that even when things are tough, there can still be good things in life. This finding helps us understand mental health better. Sometimes, when people feel very sad or worried for a long time, it is called a mental illness. For example, if someone is sad for a long time, it might be called depression, or if someone feels scared a lot, it might be called anxiety.

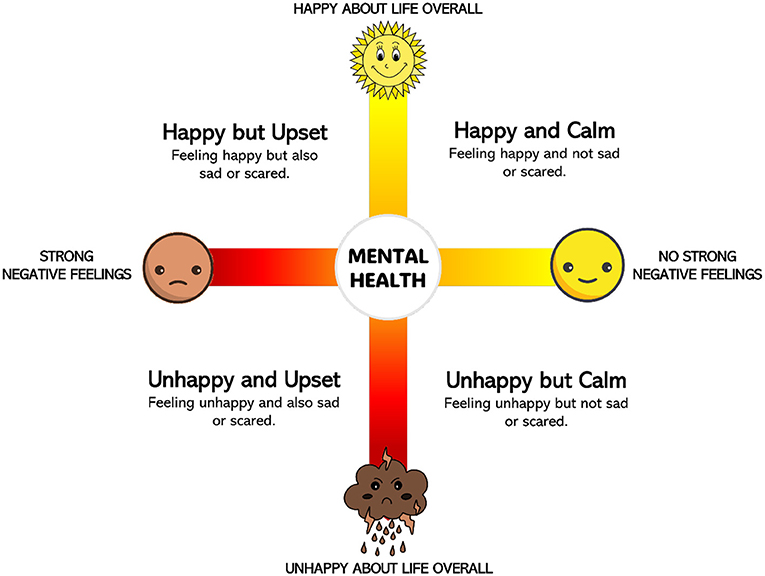

What HERO and other studies have shown is that it is possible to often feel sad or scared but still feel happy about life overall [5]. Scientists call this resilience—the ability to handle tough feelings and still find joy. Think of it like having two sliders: one for strong feelings like sadness or fear, and another for how happy you feel about life overall (Figure 1). These sliders can move separately. You might feel worried or sad but still feel good about your life and enjoy it.

- Figure 1 - This picture shows two “sliders” for how we can feel—our mental health.

- One slider shows strong feelings, like sadness, fear or worry, which people sometimes call mental illness. The other slider shows how happy we feel with life—our wellbeing. This means we can feel sad or worried but still enjoy life, or we might have no strong negative feelings but still not feel happy. This idea comes from research by Keyes [5] and shows that mental health is more than not being sad or having a mental illness—it’s also about how happy we are with life overall.

What Helps Children Feel Better?

In our research, we wanted to learn how to help children in children’s homes feel as happy and safe as possible, and how to support them with problems that make them feel sad or afraid.

We found that children feel better when adults listen to them and take their thoughts seriously, even if they still feel sad or scared sometimes. That is why it is important to support children’s participation in decisions and to teach adults how to really listen. We also found that stress from school affects how children feel. This shows that things like extra school support, tutoring, or caring teachers might help improve their wellbeing. We also wanted to learn more about what helps build resilience in kids who face tough emotions. Things like friends, expressing feelings, or learning new skills might help. So can special programs where kids feel supported and safe.

One limitation of our study is that we only asked children how they felt at one moment in time. But feelings can change! We also only spoke with children who live in children’s homes. Sometimes, when children cannot live with their own parents, they live instead with other parents, called foster parents. It is important to also listen to those children, to learn how they feel and what they want to share. To do this, we have started a new study called CHAMP. Research is like building steps, one after another. We are happy to keep learning, with the help of many people who care about children who cannot live with their own parents.

Every Voice Matters

Our research shows that it is important to listen to children who live away from their parents, understand their worries, and support them. This can mean making sure their voices are heard, helping with school stress, or helping them feel strong and confident. Every child deserves to feel safe, loved, and happy, no matter where they live. With more research, we hope to find new ways to help all children feel good and thrive.

Glossary

Children’s Home: ↑ A children’s home is a place where children live when they cannot stay with their parents. Children live with other kids and adults who take care of them.

Mental Health: ↑ Mental health is how people feel inside—whether they are happy, sad, worried, or something in between.

Mental Illness: ↑ Mental illness is when the mind, like the body, can get sick. It affects thoughts, feelings, or behaviors, making daily life harder, but people can get help to feel better.

Depression: ↑ Depression is when someone feels very sad or tired for a long time. They may not enjoy things they usually like.

Anxiety: ↑ Anxiety is when someone feels very worried, nervous, or scared a lot, even if nothing dangerous is happening. It can make simple things feel hard.

Resilience: ↑ Resilience is the ability to stay strong and find joy even when things are tough. It is like being able to bounce back after a hard time.

Foster Parents: ↑ Foster parents are adults who take care of children who cannot live with their parents. They live with them in their home all the time and look after them.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Œuvre Nationale de Secours Grande-Duchesse Charlotte and Fondation Juniclair, and also the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR, INTER/MOBILITY/2022/ID/16989832) for paying for the study. This research would not have been possible without the help of many people and groups who supported us: all the kids, caregivers, and children’s homes that took part, researchers from other countries, like Scotland, Australia and Germany, who gave us good ideas, as well as the Office National de l’Enfance (ONE), Fédération des Acteurs du Secteur Social (FEDAS), Ombudsman fir Kanner a Jugendlecher (OKaJu), Association Nationale des Communautés Éducatives et Sociales (ANCES), FleegeElteren Lëtzebuerg, and UNICEF Luxembourg.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. This work received AI assistance exclusively for English language refinement from OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-5). All ideas, analyses, and conclusions presented in this article are solely those of the authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Original Source Article

↑Engel de Abreu, P. M. J., Kumsta, R., and Wealer, C. 2022. Risk and protective factors of mental health in children in residential care: a nationwide study from Luxembourg. Child Abuse and Neglect. 146:106522. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106522

References

[1] ↑ Kumsta, R., Kreppner, J., Kennedy, M., Knights, N., Rutter, M., and Sonuga-Barke, E. 2015. Psychological consequences of early global deprivation an overview of findings from the English & Romanian Adoptees Study. Eur. Psychol. 20:138–51. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000227

[2] ↑ van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Duschinsky, R., Fox, N. A., Goldman, P. S., Gunnar, M. R., et al. 2020. Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children 1: a systematic and integrative review of evidence regarding effects on development. Lancet Psychiatry 7:703–20. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30399-2

[3] ↑ González-García, C., Bravo, A., Arruabarrena, I., Martín, E., Santos, I., and Del Valle, J. F. 2017. Emotional and behavioral problems of children in residential care: screening detection and referrals to mental health services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 73:106. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.12.011

[4] ↑ Tarren-Sweeney, M. 2008. The mental health of children in out-of-home care. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 21:345–9. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32830321fa

[5] ↑ Keyes, C. L. M. 2005. Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73:539–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539