Abstract

Parkinson’s is an illness involving damage to the parts of the brain that help people move their muscles, including the muscles used to speak. Researchers are beginning to discover how group singing can help people living with Parkinson’s to communicate better, and we wanted to learn more. In this study, we had groups of people living with Parkinson’s sing in a choir program every week for 12 weeks. By the end of the program, we found that group singing improved how low participants could sing and how long they could sing one note. We also found that group singing helped the participants sing one note with more stability. Overall, the results of our study show the benefits of group singing and its potential to help people living with Parkinson’s.

What is Parkinson’s?

Parkinson’s is an illness involving damage to the parts of the brain that help people move their muscles [1]. Some symptoms may include uncontrollable shaking or trembling, stiff or tight muscles, and difficulty keeping balance. Parkinson’s can also affect the muscles used in speech. For example, breathing might be harder because it requires muscles to help with inhaling and exhaling. Speaking may be another challenge because several muscles are needed to talk, such as the tongue, throat muscles, and muscles around the mouth [2].

As a result, people living with Parkinson’s (PwP) might talk more quietly, speak with a rough and breathy voice, and speak less clearly [3]. Imagine if you had a hard time talking to your friends because your voice was very soft or shaky. It might make it hard for people to understand you and for you to tell them what you want to say. This can make vocal communication really hard and even frustrating for PwP because they cannot express themselves in the way that they used to before developing Parkinson’s. Based on their voice changes, other people may think PwP are being cold or uninterested. As a result, PwP may find talking to people too difficult and spend less time with others or at social places. Over time, this can create feelings of loneliness that could eventually turn into mental health struggles, like depression and anxiety [3]. Improving their vocal quality and making their voices stronger and clearer could help PwP share their thoughts and needs more easily.

Our research group was curious if singing could help the voices of PwP. Other researchers have found that singing can help improve vocal communication for PwP [4]. Singing involves practicing different vocal techniques, like singing high and low notes and holding notes for longer periods. These techniques can be like exercise for the voice, making it stronger and steadier. Singing may help train the muscles involved in producing speech because it is like a workout for all the body parts involved in communicating, including the lungs and vocal cords! Participating in group singing may provide other benefits too, such as a better mood and feelings of being connected to the community [5]. Also, group singing is fun!

What Did We Do?

We wanted to learn more about how group singing improves communication for PwP. To do this, we started two community choirs for PwP, each with 14 people. These groups ran weekly for 12 weeks. During each session, participants completed around 10 min of warm up exercises, like breathing and vocal exercises. Afterwards, they spent 40 min learning and practicing different songs. The singers were encouraged to practice the songs at home too.

To understand whether people’s vocal communication improved from singing, we tested five main vocal skills: (1) We tested vocal range by asking participants to sing their lowest and highest notes. We measured the lowest and highest notes based on their pitch, similar to how you would hear notes on a piano (measured in hertz) (read more about this in Hear and There: Sounds from Everywhere!). (2) We tested loudness by asking participants to sing “ah” as loud as they could (measured in decibels). (3) We tested duration by asking participants to sing “ah” as long as they could (measured in seconds). We also tested vocal quality in two different ways: (4) jitter, which is how steady the voice is, and (5) shimmer, which is how smooth the voice sounds. Together, jitter and shimmer help us understand how clear the voice sounds. Participants completed these tests at the start and end of the 12-week choir program so that we could compare their vocal skills before and after singing. Based on previous research, we predicted that the participants would improve their vocal skills by the end of the choir program.

What Did We Find?

Here is what we discovered about how singing in a choir affected people’s vocal skills.

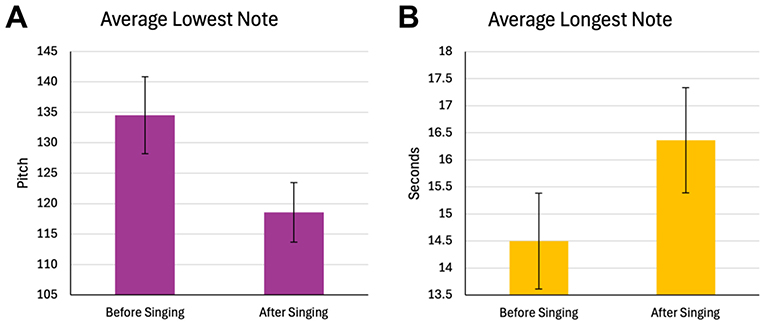

Vocal range: participants improved in their lowest note by the end of the choir program, meaning they could sing a lower note than they could sing before the program (Figure 1A). However, singing did not improve their highest note.

- Figure 1 - (A) Shows the average pitch (measured in hertz) the participants sang when asked to sing “ah” as low as possible.

- After the choir program, participants could sing lower notes than when they first started. (B) Shows that after group singing, participants could hold a note for longer than when they first began the choir program.

Loudness: singing improved how loud the participants could sing in the one community choir, but not in the other. This might mean that the way the choir was led—like the exercises and support the choir leader gave—can make a difference in how people’s voices improve.

Duration: participants could sing “ah” for a longer time by the end of the program compared to before the program (Figure 1B). The change in duration does not seem to be very large, but it can lead to a tremendous improvement in a person’s communication skills!

Vocal quality—Jitter: participants sang “ah” with more stability in pitch after singing in one choir, but not in the other. Just like with loudness, this might be because of differences in how the choirs were run or taught.

Vocal quality—Shimmer: participants improved their shimmer, meaning they sang “ah” with a smoother sound compared to when they first started the choir program.

You may wonder whether everyone improved from singing. Some of the participants may have benefited more than others, which means that their experiences may have been different compared to the overall group. To show these differences, the graphs have error bars (the long black lines on the colored bars). Error bars represent the range of the group’s data and how much the participants varied. While we could graph each person’s individual experience, this can often look very messy, especially if a study involves several participants. Error bars help us understand the range of different data in a clean and simple fashion.

What do our Results Mean?

This study showed that group singing helped PwP improve several important aspects of their voices. This is a really important discovery because there is currently no cure for Parkinson’s. Group singing is a safe, fun activity, so it is a great way to help PwP communicate better. Improving their vocal quality makes it easier for PwP to talk to other people. Better communication helps them share their thoughts, feelings, and needs. Just like how practicing a sport makes you better at it, practicing using your voice can make it stronger and support communication with everyone around you.

Furthermore, group singing may be a powerful tool for illnesses beyond Parkinson’s. Singing may be helpful for people living with other types of disorders, like lung disease. Our results also leave researchers wondering if group singing could help people in other ways, such as by reducing pain and anxiety. Overall, it looks like there is more to group singing than we originally believed, and much more research needs to be done to discover all of its benefits (Figure 2)!

- Figure 2 - This cartoon summarizes the main ideas of our article.

- We hope you share this with your friends and family!

Glossary

Parkinson’s: ↑ A disease involving the damage of the brain regions related to muscle movement.

Vocal Communication: ↑ Communicating to others using your voice and spoken words.

Vocal Quality: ↑ The way we describe someone’s voice, such as clear, raspy, and creaky.

Vocal Range: ↑ The lowest and highest note a person is able to sing.

Loudness: ↑ The loudest a person can sing “ah” (measured in decibels).

Duration: ↑ The length of time a person can sing “ah” (measured in seconds).

Jitter: ↑ The amount of change in loudness during speaking or singing.

Shimmer: ↑ The amount of change in pitch during speaking or singing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by SingWell, a SSHRC Partnership Grant project awarded to FR. Special thanks to Singing with Parkinson’s and U-Turn Parkinson’s. We are also grateful for the partnership of Parkinson’s Canada, and choir directors Paula Wolfson and Heitha Forsyth.

AI tool statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Original Source Article

↑Good, A., Earle, E., Vezer, E., Gilmore, S., Livingstone, S., and Russo, F. A. 2025. Community choir improves vocal production measures in individuals living with Parkinson’s disease. J. Voice 39:848.e7–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2022.12.001

References

[1] ↑ Sveinbjornsdottir, S. 2016. The clinical symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 139(S1):318. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13691

[2] ↑ Simonyan, K., and Horwitz, B. 2011. Laryngeal motor cortex and control of speech in humans. Neuroscientist 17:197. doi: 10.1177/1073858410386727

[3] ↑ Swales, M., Theodoros, D., Hill, A. J., and Russell, T. 2021. Communication and swallowing changes, everyday impacts and access to speech-language pathology services for people with Parkinson’s disease: an Australian survey. Int. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 23:70. doi: 10.1080/17549507.2020.1739332

[4] ↑ Higgins, A. N., and Richardson, K. C. 2018. The effects of choral singing intervention on speech characteristics in individuals with Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory study. Commun. Disord. Q. 40:195. doi: 10.1177/1525740118783040

[5] ↑ Weinstein, D., Launay, J., Pearce, E., Dunbar, R. I. M., and Stewart, L. 2016. Singing and social bonding: changes in connectivity and pain threshold as a function of group size. Evol. Hum. Behav. 37:152. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.10.002