Abstract

Just as rainstorms can lead to vibrant rainbows, difficult times can lead to remarkable personal growth, which is known as post-traumatic growth (PTG). Many people experience extremely difficult situations called traumatic events, which can negatively impact their lives in many ways. However, people can change and experience growth after facing these tough times. PTG can positively transform a person’s life, including finding personal strengths and improving their relationships. The process of PTG involves understanding the trauma and its meaning, seeking support from others, and changing how people view the trauma in their life’s story. Various strategies can help promote PTG, such as discussing feelings with others and practicing mindfulness. Learning about PTG can help us understand how we, and others, can grow even after the hardest storms, ensuring these situations do not stop us from living our best lives.

What is Trauma?

Trauma is a negative physical or emotional response to a scary or difficult experience. Some traumatic events include natural disasters, death of a loved one, violence, accidents, and abuse. Following a traumatic event, common reactions include feeling anxious, trouble sleeping or concentrating, constantly thinking about the event, rapid breathing, increased heart rate, and restlessness. In the long run, people can experience multiple reactions because of the trauma, including flashbacks, unpredictable emotions, difficulties in relationships, and physical symptoms like headaches and nausea. Given that these symptoms of trauma can be distressing and disrupt a person’s life for a long time, understanding trauma is important because it sets the stage for recognizing the transformative power of post-traumatic growth (PTG).

What is Post-Traumatic Growth?

PTG is not experienced by everyone; it is deeply influenced by a person’s culture. Different cultures have unique ways of understanding and promoting growth after trauma. For example, many Indigenous cultures emphasize community healing and collective resilience, using rituals and storytelling to process trauma and foster growth. In Japan, the concept of kintsugi—repairing broken objects with gold—symbolizes the beauty of transformation after adversity. This is the essence of PTG. Imagine you are playing with your favorite cup, and it accidentally breaks. You might be upset that it is ruined, but using kintsugi, the cracks in the cup can be filled with gold, making it more beautiful than it was before. Thus, the cracks become an important part of its story. PTG can be like kintsugi for people. We go through many tough experiences and may feel like they have broken us. However, just like broken objects can be beautified, we too can grow after tough times.

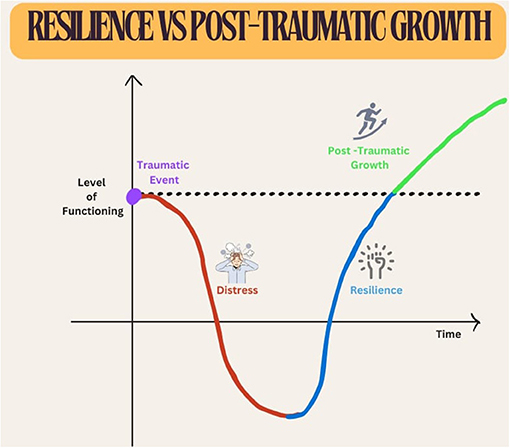

Psychologists have defined PTG as the positive mental and emotional changes resulting from a person’s struggle with trauma or challenging situations [1]. PTG could be confused with resilience, which is the ability to bounce back after experiencing a challenging situation. While showing resilience would mean that one glues the broken object back together so that it looks like it did before it broke, PTG is like gluing the object back together with gold, making it more beautiful than it was before breaking (Figure 1).

- Figure 1 - While resilience means getting back to one’s normal level of functioning before the traumatic event, PTG implies some sort of growth and transformation that is experienced after the traumatic event.

- Thus, in many ways, resilience is necessary for PTG because it comes before PTG. The PTG line shows how people can exceed the level they were functioning at before the trauma occurred.

Areas of Post-Traumatic Growth

There are five key areas in which people can experience PTG [2]:

• New possibilities: difficult experiences can open people’s eyes to new possibilities. Maybe someone who lost their job finds a new passion they never considered previously or rediscovers something they wanted to do in the past but were never able to. Often, individuals experience a shift in their values and priorities after experiencing trauma, which opens them up to new opportunities.

• Better relationships: going through tough times can bring people closer together. During these times, individuals share their feelings and support each other, which can make their relationships stronger. People can experience increased emotional sensitivity, a sense of belonging, and they may grow closer to the people in their lives who stood by them during the tough period.

• Personal strength: after overcoming a tough situation, most people begin to realize they are far stronger than they thought. It is like discovering you have superpowers you were unaware of. For example, someone who has recovered from a chronic illness might discover they have the strength to face other challenges with confidence.

• Spiritual changes: difficult events can deepen or change people’s spiritual beliefs, which means the belief in something greater than themselves like God, purpose, nature, or the universe. Spiritual changes could include spending time in nature, meditation, or prayer, or finding a sense of purpose in helping others.

• Appreciation of life: after experiencing something difficult, people often begin to value the little things in life, like spending time with their loved ones, enjoying nature, or feeling grateful for the ordinary things they otherwise took for granted, like their favorite book or a warm cup of tea. People may change their priorities so that these small things are valued.

These areas of growth demonstrate the rich impact that PTG can have in multiple aspects of an individual’s life, allowing them to turn their challenges into meaningful changes.

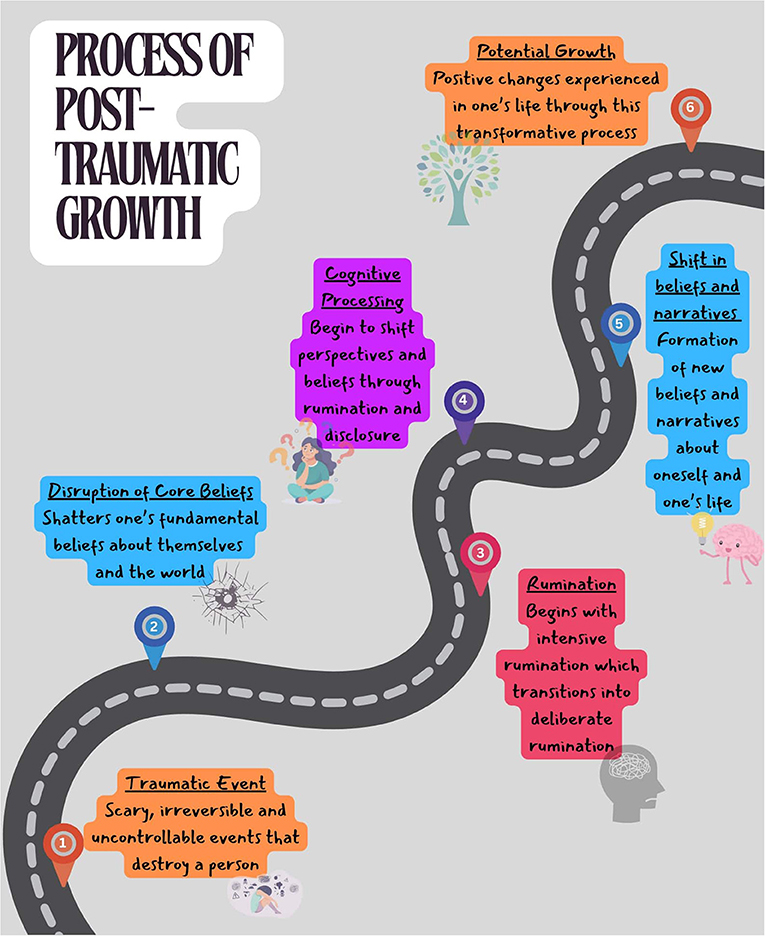

Process of Post-Traumatic Growth

PTG occurs through several stages [1, 3] (Figure 2). The first stage is the traumatic event itself, which can be like an earthquake, shaking and destroying the basic structure of an individual’s life. These events are generally very scary, irreversible, and uncontrollable. Just as an earthquake fractures the ground, traumatic events cause a big impact on individuals, which can completely shake their core beliefs—the assumptions people hold about themselves and the world that shape their understanding and guide their actions.

The next stage, called rumination, begins with recurrent thoughts. People might find themselves constantly thinking about the traumatic event, which causes them a lot of anxiety, similar to assessing the damage after an earthquake. People can eventually begin to think about the event on purpose, which is called deliberate rumination, as they try to understand its meaning in their lives. The rumination stage is similar to assessing the damage after an earthquake, sorting through debris to find the objects that remain. Deliberate rumination helps people develop new perspectives, by understanding why the event happened and its impact on their lives. It is like rebuilding broken structures after an earthquake. This process, called cognitive processing, is aided through sharing experiences and emotions with other people, which helps the person who experienced trauma to gain new perspectives.

Ruminating on and processing the traumatic event can lead to a shift in a person’s core beliefs and personal stories. People may find new beliefs about themselves, others, and the world, and can develop new goals and stories about their lives—like rebuilding stronger structures after an earthquake. Finally, as people find new core beliefs and narratives, they may begin to experience positive changes in multiple areas of their lives, which have been described above. Like a rebuilt environment, these changes become part of their lives, improving their ability to deal with future challenges. This growth is not about forgetting the trauma, but instead including it into a new, strengthened identity.

Overall, the process of PTG requires a lot of effort. To achieve personal transformation, this journey also requires an understanding and challenging of one’s beliefs.

Strategies to Promote Post-Traumatic Growth

Now that we understand more about PTG, here are some ways that it can be promoted. First, social support is important for the cognitive processing part of the PTG process. Support from family, friends, and other significant people can help a person express their emotions and change their beliefs and narratives, by introducing the person to new perspectives. It can be especially helpful to share with those who have experienced similar traumas, since that can help people to feel that they are not alone in their experiences [1, 3, 4]. Sometimes it can also help to talk to a professional like a counselor. Counselors are trained to help people move through the process of reaching PTG. Remember, it is okay to ask for help—it makes you stronger!

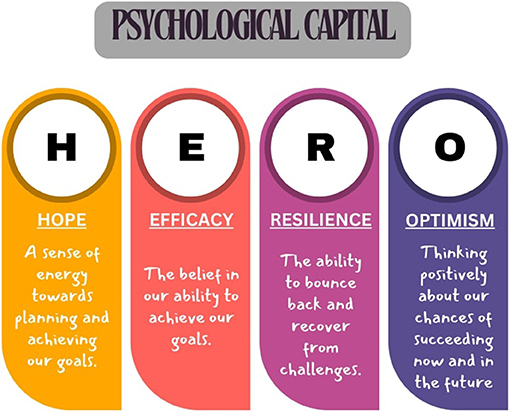

Building psychological capital is another way to promote PTG. Psychological capital is a combination of four healthy resources that enhance wellbeing. These resources can be summarized using the acronym HERO: hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism [5]. Each of these resources has been shown to potentially enhance PTG (Figure 3) [6–9]. Practicing mindfulness through simple activities like meditation, yoga, and focusing on everyday activities like eating and walking can improve psychological capital [10]. Adopting a meaning-focused coping strategy, which means trying to find the positive meaning of the event in their lives, can also help people build psychological capital [11]. This also helps to move through the cognitive processing stage of the PTG process.

- Figure 3 - The four components that make up psychological capital.

Technology also offers new opportunities for promoting PTG. Online support groups, mental health applications, and virtual therapy provide accessible resources for those seeking help. These tools can offer social support, guided mindfulness practices, and cognitive-behavioral techniques that facilitate PTG. However, it is essential to balance technology use with real-life interactions to ensure comprehensive support.

By implementing some of these suggestions, which are also helpful for enhancing everyday wellbeing, people who have experienced trauma can begin their journey of navigating through their challenges and reaching PTG—ultimately transforming their negative experiences into opportunities for growth and positive change.

Navigating the Complexities of PTG

While growth is important, we must not forget several other important aspects [12]. First, we should remember to empathize with trauma survivors, because they are often experiencing distress along with growth. Also, by talking about PTG, we are not saying that trauma is good; ideally, nobody should have to experience trauma. However, this article highlights that even those who face trauma can experience meaningful changes in their lives. Finally, not everyone who experiences trauma will experience PTG and that is okay; it is important to support everyone, no matter what their journey looks like, and recognize that every response to trauma is valid. Remember, even the darkest storms can lead to the most beautiful rainbows. Embrace your journey and know that growth is always possible.

Glossary

Chronic Illness: ↑ An illness which generally lasts for a long-time and may not have a cure, like cancer, diabetes and stroke.

Rumination: ↑ The process of having repetitive, and often negative thoughts about a person’s distress, which can prevent them from finding solutions.

Cognitive Processing: ↑ The mental process of making sense of an event by reflecting on its meaning and integrating it into a person’s life.

Psychological Capital: ↑ A collection of resources that help us enhance our wellbeing.

Mindfulness: ↑ The act of paying complete attention to the present moment without classifying the things that happen as good or bad.

Cognitive Behavioral Technique: ↑ A technique where people are encouraged to challenge and change their negative thoughts into healthier and more logical thoughts.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anand for the review of this manuscript. Anand enjoys reading about biology and health science. His specific areas of interest are cell biology and immunology. Anand’s hobbies include participating in academic competitions, managing the school newspaper, and learning more about roller coasters.

References

[1] ↑ Tedeschi, R. G., and Calhoun, L. G. 2004. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol. Inq. 15:1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

[2] ↑ Tedeschi, R. G., and Calhoun, L. G. 1996. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 9:455–71. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090305

[3] ↑ Henson, C., Truchot, D., and Canevello, A. 2020. What promotes post traumatic growth? A systematic review. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 5:100195. doi: 10.1016/j.ejtd.2020.100195

[4] ↑ Rzeszutek, M., Oniszczenko, W., and Firlag-Burkacka, E. 2017. Social support, stress coping strategies, resilience and posttraumatic growth in a polish sample of HIV-infected individuals: results of a 1 year longitudinal study. J. Behav. Med. 40:942–54. doi: 10.1007/s10865-017-9861-z

[5] ↑ Luthans, F., and Youssef-Morgan, C. M. 2017. Psychological capital: an evidence-based positive approach. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 4:339–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113324

[6] ↑ Yuen, A. N. Y., Ho, S. M. Y., and Chan, C. K. Y. 2013. The mediating roles of cancer-related rumination in the relationship between dispositional hope and psychological outcomes among childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology 23:412–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.3433

[7] ↑ Ho, S., Rajandram, R. K., Chan, N., Samman, N., McGrath, C., Zwahlen, R. A., et al. 2011. The roles of hope and optimism on posttraumatic growth in oral cavity cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 47:121–4. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.11.015

[8] ↑ Jian, Y., Hu, T., Zong, Y., and Tang, W. 2022. Relationship between post-traumatic disorder and posttraumatic growth in COVID-19 home-confined adolescents: the moderating role of self-efficacy. Curr. Psychol. 42:17444–53. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02515-8

[9] ↑ Duan, W., Guo, P., and Gan, P. 2015. Relationships among trait resilience, virtues, post-traumatic stress disorder, and post-traumatic growth. PLoS ONE 10:e0125707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125707

[10] ↑ Li, L., and Li, M. 2020. Effects of mindfulness training on psychological capital, depression, and procrastination of the youth demographic. Iran. J. Public Health 49:1692–700. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v49i9.4086

[11] ↑ Ortega-Maldonado, A., and Salanova, M. (2017). Psychological capital and performance among undergraduate students: the role of meaning-focused coping and satisfaction. Teach. High. Educ. 23:390–402. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2017.1391199

[12] ↑ Tedeschi, R. G., and Calhoun, L. G. A. 2004. “Clinical approach to posttraumatic growth”, in Positive Psychology in Practice, eds. P. A Linley, and S. Joseph (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons), 405–19. doi: 10.1002/9780470939338.ch25