Abstract

Have you ever seen a sinkhole? Sinkholes are water-filled caves, and some sinkholes in Mexico hide cultural and medicinal secrets. For the ancient Mayan civilization, sinkholes were used as water sources and ceremonial sites. Now, scientists are trying to discover new drugs within them. The mud of sinkholes contains many bacteria that can help fight other harmful microbes. Just like the medicines doctors prescribe when you have a sore throat, these bacteria use special molecules to kill the bacteria and fungi that they compete with in their environment. Unfortunately, many harmful bacteria have become resistant to common antibiotics, meaning they have evolved such that some antibiotics are less effective against them. This is why developing new antibiotics is critical. By exploring new environments, like Mayan sinkholes, we can find bacteria that make molecules that can be used as new drugs to protect us from dangerous infections.

The Sinkholes from the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico

The ancient Maya civilization was an advanced and fascinating culture that thrived in the southern regions of Mexico and Central America. Both ancient and modern Maya communities have lived surrounded by cenotes—natural sinkholes with unique ecosystems, wildlife, and shapes that have played an important role in their daily lives and traditions [1]. These Mayan sinkholes are locally referred to as “cenotes”, from the Mayan word “ts’onot”. The sinkholes are part of one of the most extensive underground rivers and cave systems in the world, and they form whenever cave roofs collapse (Figures 1A, B). To date, 6,000–7,000 sinkholes have been reported in the Yucatan peninsula, which is famous for being the site of impact of a meteorite 65 million years ago (Yes, the same meteorite that triggered the extinction of the dinosaurs, but that is another story)! Incredibly, the impact area ended up with a high density of these sinkholes, and people call it “the ring of cenotes” (Figure 1C). Overall, cenotes can be classified as coastal and inland sinkholes (Figures 1D, E) [2]. Coastal sinkholes are located near the ocean, and they have an inflow of seawater—therefore, they contain both freshwater (which flows in from Earth’s surface) and seawater (which flows in from the bottom of the sinkhole). In contrast, inland sinkholes are located in the central part of the Yucatan peninsula and contain only freshwater, from rainfall. Both sinkhole types are fascinating, which is why there are many documentary videos available, such as NatGeo’s Diving in a Sacred Maya Cave, Discovery Channel’s secrets of the sacred cenotes, and Planet Doc’s Cenote Documentary—and you can probably find other interesting videos on YouTube.

- Figure 1 - (A) A cave created by a sinkhole in the Yucatan Penninsula, Mexico.

- (B) A diver exploring a freshwater sinkhole. (C) A map with green diamonds (coastal sinkholes) and purple diamonds (inland sinkholes) to indicate where sinkholes are found, especially in the ring of “cenotes” (density of sinkholes shown with red mini diamonds). (D) Coastal sinkholes contain both freshwater from Earth’s surface and oceanwater that enters from the bottom. (E) Inland sinkholes contain only freshwater that enters from above (Figure credits: (A, B) Kay Vilchis @kayuvilchis; (D, E) Alberto Guerra @albertoguerrae).

Cenotes are not easy to access or explore, so they have remained practically untouched. To microbial scientists, undisturbed environments like these are very special, since they provide us with a chance to find unique bacteria that make novel compounds that could be developed into new drugs.

Antimicrobial Resistance is a Huge Health Problem

Bacteria living in watery environments like sinkholes need to fight off other competing bacteria, which are their enemies. To do so, they produce a variety of chemical compounds, including antibiotics, and humans have used this to our advantage. Scientists like us grow these bacteria and obtain antibiotics from them, like vancomycin to treat intestinal infections or streptomycin to treat tuberculosis. The world is facing a big problem though—bacteria are evolving tactics to avoid getting killed by some of these molecules. This bacterial trait is called antibiotic resistance. When antibiotics become ineffective, infections become difficult to treat, increasing the risk of disease spread and death. Alarmingly, some scientists have predicted that, if urgent measures are not taken, more than ten million deaths could result from infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria worldwide within the next 30 years [3]. A world without antibiotics could be a good starting point for a horror film!

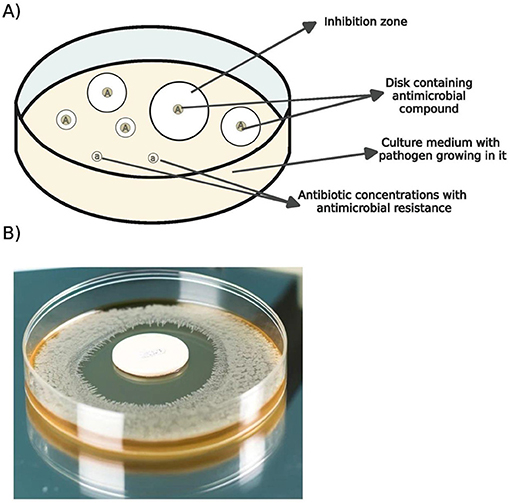

A quick way to know if dangerous microbes are resistant to antibiotics is by exposing them to antibiotics when they are growing on a plate of agar, which is a kind of gelatin used to grow microbes in the laboratory. Scientists can expose bacteria to different amounts of antibiotic by applying the drugs on a small disk and setting the disk on the agar plate where the bacteria are growing (Figure 2). If the amount of antibiotic on the disk stops the bacteria from growing, there will be a clear circle around the disk where the antibiotic was placed, called the inhibition zone. If bacteria can still grow perfectly well in the presence of the disk, it may indicate that the bacteria are resistant to that antibiotic (Figure 2A). Sometimes a higher concentration of the antibiotic is needed to completely kill the bacteria, and using a lower concentration may allow some bacteria to figure out how to get rid of the antibiotic. Then, the next generation of bacteria will have acquired resistance to that antibiotic. This is why doctors ask you to keep taking your antibiotic treatment, even if you feel better before you finish the prescription. Bacteria are so tiny and there are so many of them that one bacterial cell may somehow have a way of getting rid of some of the antibiotic you are taking. If you do not make sure to kill all the bacteria, including those that may be somewhat resistant, then you are helping the resistant bacteria to prosper. That means the next time those bacteria cause an infection, it will be harder to treat and you will need higher doses or different kinds of antibiotics to treat it.

- Figure 2 - A laboratory test can measure how well antibiotics inhibit bacterial growth.

- (A) Circles labeled “A” show different antibiotic concentrations on a surface with bacteria. Inhibition zones show where bacteria did not grow. “a” marks areas with antibiotic concentrations that can create antimicrobial resistance. (B) Bacteria exposed to an antibiotic disk on an agar-filled petri dish (Image created using ChatGPT-4).

Antibiotic resistance happens naturally over time because bacteria reproduce really fast, and they can change and adapt rapidly by picking up, changing, or getting rid of certain genes. Unfortunately, improper use of antibiotics has sped up the development of antibiotic resistance. So, do your part, listen to your family doctor, and follow all instructions when taking antibiotics!

New Antibiotics From Bacteria in Mayan Sinkholes

Since antimicrobial resistance is a huge problem, our research group focuses on exploring unique environments that may lead to the discovery of novel antibiotics. One of our methods is actually pretty cool—we get to dive into sinkholes and collect sediments (bottom mud or sand) so we can grow the bacteria living there, to see if they make compounds that could be used to create new medicines. You can watch us here. Once we get the sediment sample, we put it in liquid or solid culture media containing all the nutrients that the bacteria need to grow (Figure 3). Once the bacteria grow, we remove their DNA. The full set of DNA instructions to “build” an organism is called the organism’s genome. When we extract the DNA, we get the genomes of many bacteria that were in the original sediment sample, which we can then classify and name. We also look for the individual instructions, called genes, that have the information to build chemical compounds called metabolites (Figure 3). Metabolites help bacteria survive in various environments. In bacteria, the instructions to build the metabolites are all organized together in specific regions of the DNA, known as biosynthetic gene clusters. We search for these gene clusters using computer programs that help us examine the bacterial DNA. Our objective is to discover biosynthetic gene clusters that produce metabolites that can be used in medicine, such as antibiotics, antifungals, and anticancer compounds.

- Figure 3 - Sediment samples (green stars) are collected from coastal and inland sinkholes, and they are used to grow bacteria in both liquid and solid culture media.

- DNA is recovered from the media, analyzed, and assembled into bacterial genomes. The bacterial species and active metabolites they produce are then characterized.

How can Sinkholes Help Solve the Antimicrobial Resistance Crisis?

When we explored the genomes of the microorganisms living in the sediments from one of the coastal sinkholes we dove into, we found DNA instructions to create metabolites similar to some known compounds that help fight harmful bacteria. That means sinkhole bacteria can make antibiotics similar to some of those in use today, as well as some metabolites that can fight disease-causing fungi. We even found genes that encode instructions to make metabolites similar to known anticancer compounds. These observations are very important, and they mean that bacteria living in the sediments of these incredible and beautiful underwater caves could be used as a source for new compounds that can be turned into medicines to kill bacteria that existing medicines cannot kill, like antibiotic resistant bacteria. Finding the genes coding for these important chemical compounds in the microbes living in the sediments of what once was known as the “Mayan underworld” gives us hope of finding a solution to one of the greatest health crises that the world will be facing in the next 30 years! So, fingers crossed and Go Science!

Glossary

Antibiotic: ↑ A type of medicine that kills harmful bacteria.

Antibiotic Resistance: ↑ Natural process by which bacteria can evolve to become strong enough to survive chemical compounds (medicine) that normally kills them.

Sediments: ↑ Tiny bits of rock, soil, and materials that settle at the bottom of sinkholes and other waterbodies.

Culture Media: ↑ A set of substances that provide essential nutrients for bacteria to grow and multiply under laboratory conditions, commonly in liquid (like broth) or solid (like jelly) forms.

Genome: ↑ The complete set of genetic material (genes) in an organism.

Genes: ↑ DNA instructions in cells that determine traits and functions of organisms.

Metabolites: ↑ Chemical substances formed during metabolism that can be essential for growth, communication, and interaction with the environment.

Biosynthetic Gene Clusters: ↑ A group of all genes responsible for the production of metabolites or potential medicines

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT) for the postdoctoral fellowship (362331) (PSM) and project A1-S-10785 (APD).

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Original Source Article

↑Suárez-Moo, P., and Prieto-Davo, A. 2024. Biosynthetic potential of the sediment microbial sub-communities of an unexplored karst ecosystem and its ecological implications. MicrobiologyOpen 13:e1407. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.1407

References

[1] ↑ Schmitter-Soto, J. J., Comín, F. A., Escobar-Briones, E., Herrera Silveira, J., Alcocer, J., Suárez-Morales, E., et al. 2002. Hydrogeochemical and biological characteristics of cenotes in the Yucatan Peninsula (SE Mexico). Hydrobiologia 467, 215–28. doi: 10.1023/A:1014923217206

[2] ↑ Suárez-Moo, P., Remes-Rodríguez, C. A., Márquez-Velázquez, N. A., Falcón, L. I., García-Maldonado, J. Q., and Prieto-Davó, A. 2022. Changes in the sediment microbial community structure of coastal and inland sinkholes of a karst ecosystem from the Yucatan peninsula. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05135-9

[3] ↑ De Kraker, M. E., Stewardson, A. J., and Harbarth, S. 2016. Will 10 million people die a year due to antimicrobial resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 13, e1002184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002184