Abstract

Can you picture cows grazing on a meadow of grass? Did you know that there are also “cows” under the sea that graze on seagrass meadows? Dugongs—a type of sea-cow—are threatened with extinction, mainly as a result of human activities and loss of their main food source, seagrass. Seagrasses are a group of flowering plants that grow in the ocean! Seagrasses are important not only as a food source for dugongs, but they provide a home for many animals, absorb carbon dioxide aiding in climate change mitigation, and so much more! However, seagrasses are declining globally, which is bad news not only for dugongs, but for humans as well. Luckily, dugong presence can aid scientists in understanding the health of seagrasses in an area, as well as help scientists locate and protect our important seagrass ecosystems.

Dugongs—Vegetarians of The Sea

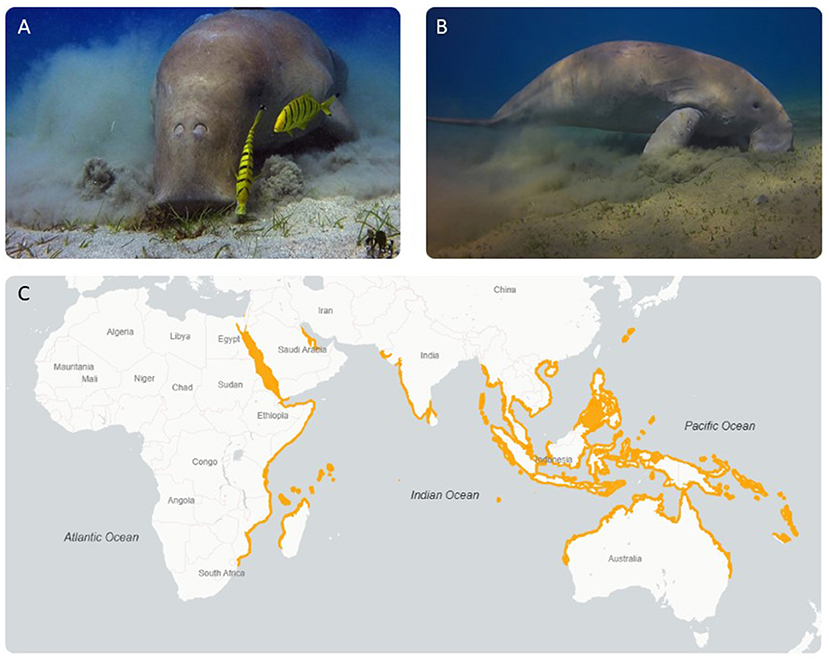

Dugongs are mammals that live in the ocean. They have round bodies and smooth skin. You may spot them above the water, as they come to the surface to breathe every 3–12 minutes through their unique snouts, which look like a cross between an elephant’s trunk and a dolphin’s beak (Figures 1A, B). Dugongs can grow to around 3 meters long, propelling themselves through the water with a wide fluked (dolphin-like) tail. They are found in warm, shallow coastal waters of 46 countries across the Indian and Pacific Oceans (Figure 1C). As migratory animals, they can sometimes travel large distances in search of food. Dugongs are also important to many Indigenous people around the world, as part of their culture and a traditional source of food.

- Figure 1 - (A, B) Dugongs feeding on seagrass on the ocean substrate.

- You can see their unique snouts and how these animals use it to munch on their favorite food: seagrass. (C) A map showing (in orange) where dugongs can be found [Figure credits: (A, B) Ahmed Shawky; (C) The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) 2015. Dugong dugon. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. https://www.iucnredlist.org.

Dugongs belong to the order (a group of animals which are similar) Sirenia, which contains only four species worldwide [1]. Three of these are different species of manatees (found in North and South America and West Africa), which are somewhat larger and look slightly different to dugongs, with paddle-shaped tails, a different mouth shape, and “nails” on their flippers. The fourth species is dugongs. Dugongs and manatees are both herbivores, which means they are vegetarians that only eat plants. Both dugongs and manatees are known as “sea cows” because their diet consists mainly of seagrass, the only flowering plant found in the sea. Dugongs are only found in marine (saltwater) environments, while manatees rely on both freshwater and saltwater. This makes dugongs the only vegetarian mammals that live in the sea.

Dugongs have a long lifespan—they can live up to 70 years. However, dugongs have a low birth rate (one calf every 3–7 years) and take many years to start having calves (babies), which live with their mothers for around 2 years. These characteristics makes dugongs vulnerable to decreases in their numbers. Being large animals, dugongs do not have many natural predators, but dugong calves and sick or injured dugongs are vulnerable to being eaten by large sharks, killer whales, and saltwater crocodiles. However, the main threats to dugongs are caused by humans, including, loss of their seagrass habitats, being hit by boats, and getting tangled in fishing nets. As a result, dugongs are decreasing worldwide and are vulnerable to extinction. Therefore, dugongs and their seagrass habitats need extra attention and protection.

Seagrass—Champions of The Ocean!

Seagrasses are extremely important for animals that live underwater, and even for humans! They are the main food source not only for dugongs, but also for other marine animals like fish and turtles [2]. Seagrasses are also home to many animals, including fish that humans like to eat. These plants are also champions in our battle against climate change, because they help to lock carbon away into the sediment.

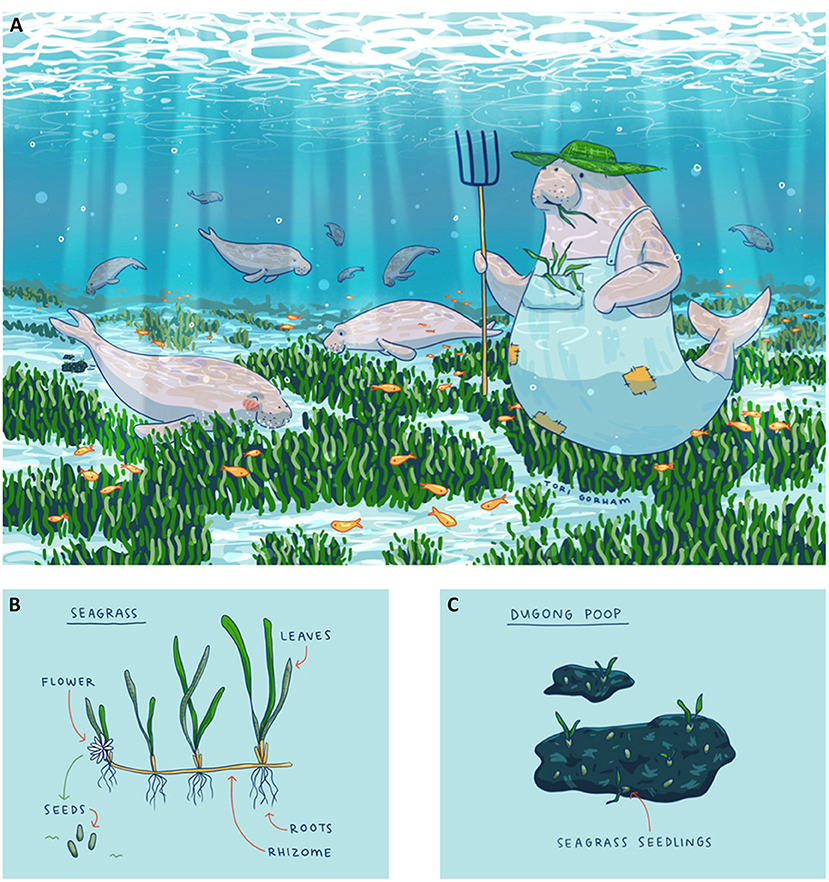

Seagrasses have leaves, roots, and rhizomes, just like many of the plants that grow on land, but they live underwater! Seagrasses reproduce through seeds developed from flowers, creating genetically unique plants, but they can also create exact copies (clones) of themselves (Figure 2B). Because seagrasses are plants, they need light to undertake photosynthesis, so are generally found in shallow waters. Seagrasses come in all shapes and sizes. Some seagrasses, like paddle weed, are very small and have paddle shaped leaves the size of your thumb, while others, like ribbon weed, resemble large blades of grass and can grow to the length of your arm, or even taller than you. You can find seagrasses all around the world, off the coasts of all continents except Antarctica, where it is too cold for seagrass to grow. In fact, temperature plays a large part in where seagrasses live, with some species living in warm tropical oceans and others in cool temperate waters.

- Figure 2 - (A) Dugongs eating their favorite food (seagrass!) and creating bare sand patches called “feeding trails”.

- (B) Adult seagrass, as well as seagrass seeds that are produced by flowers. Seeds can sprout on the seafloor, turn into seagrass seedlings, and then grow into adult plants to complete their lifecycle. (C) Dugong poo can contain seagrass seeds, which can germinate into seagrass seedlings. Therefore, when dugongs move, they can help spread seagrass seeds to new areas (Image credit: Tori Gorham Illustration).

Over the last 100 years, the world has lost around 19% of its seagrasses, and unfortunately, in some places we are still loosing one to two football fields of seagrass every hour! Seagrass meadows are being damaged by coastal development, like harbors, and more recently, by climate change. When we lose seagrasses, we also lose all the benefits that they provide to the environment and to us, including providing a food source for dugongs.

Dugongs Can Be Good “Seagrass Farmers”

Dugongs spend much of the day feeding on seagrass, farting (eating a vegetarian diet will do that to you), and pooing. They eat a lot: about 40 kilograms of seagrass every day, which is equal to 130 lettuce heads. Dugongs eat both seagrass leaves and rhizomes, leaving bare sand patches through the seagrass meadow as they feed (Figure 2A). In some areas they are considered “seagrass farmers”, because over time their feeding behavior changes which seagrass species are most commonly found in a meadow [3]. Small, fast-growing species are generally the first to form a seagrass meadow, which are the species dugongs prefer to eat. Smaller seagrass species have high nutritional value, and by dugongs continually removing small seagrasses as they eat, over time, they stop other slower growing seagrass species, that are less nutritious, from taking over. This process of dugong grazing influencing which seagrass species are present is known as a positive feedback loop, keeping the ecosystem in a state that is favorable for dugongs. Another positive feedback loop occurs when dugongs poo. If the poo contains seagrass seeds, new seagrass plants can also establish and grow from this nutrient-rich fertilizer package (Figure 2C). In fact, seagrass seeds that pass through a dugong are more likely to germinate and grow than seeds that do not. By spreading seeds this way, dugongs also increase the genetic diversity of seagrass meadows. You can think about diversity of a species like Superhero characters. For example, when Thor and Black Widow (both human superheros) combine their strengths, they are stronger in the face of enemies. When a single seagrass species (for example paddle weed) has both Thor’s and Black Widow’s in the meadow, they are stronger in the face of human impacts, including climate change.

When Seagrass Disappears, So Do Dugongs

If a seagrass meadow disappears because of an extreme weather event (e.g., cyclone), dugongs will move to find seagrass elsewhere, sometimes, far away. Scientists have tracked some dugongs traveling hundreds of kilometers between patches of seagrass. In fact, the longest distance recorded by one dugong is 1,000 km [4], which is the same as traveling from Paris to Berlin. When there is not enough seagrass to eat, dugongs will delay having calves until seagrass becomes healthier. Over time, this can mean that the number of dugongs in an area will decrease.

Near a small coastal town in Western Australia, there is a beautiful body of water called Exmouth Gulf. It is home to a diversity of marine life, including dugongs and seagrass. Dugongs can be found grazing on seagrass throughout the year, and the Gulf contains critical habitat for dugongs in this part of the world. However, in 1999, something interesting happened. Widespread damage to seagrass in Exmouth Gulf occurred from a tropical cyclone. The following year, dugong numbers in the Gulf were unusually low, but 400 km south, in a location called Shark Bay, there was an increase in the number of dugongs. Shark Bay is known for its lush seagrass meadows, and during the cyclone, these meadows did not experience the same damage as the meadows in Exmouth Gulf. Scientists believe that the dugongs in Exmouth Gulf undertook the long journey south to find food [5]. Because it is difficult to identify individual dugongs and there was no tracking data, it is hard to know how long the dugongs may have stayed in Shark Bay. However, several years later, there were larger numbers of dugongs back in Exmouth Gulf, suggesting that the seagrass had returned.

Dugongs Can Help Scientists Find Seagrass

For the tropical seagrasses that dugongs eat, dugongs are an important indicator species, meaning they can aid in telling scientists about of the presence and health of seagrass meadows [6]. Seagrass meadows occur on the seafloor, often in murky water, making it hard to keep track of where the seagrass is and how well it is doing. Dugongs feeding on seagrass come to the surface every few minutes to breathe, so they can be detected from the air across these seagrass habitats. Scientists can fly planes or drones over these large areas and record where the dugongs are, which then tells them where the seagrass may be.

You Can Help Protect Dugongs and Their Homes Too!

We need to protect and conserve our seagrass meadows to ensure dugongs can thrive in the future. Many people, both scientists and communities, are helping to protect these ecosystems and you can become part of the team. Here are some tips on how you can help!

• First, if you live near the ocean, you can be a “dugong detective” by visiting your local seagrass meadow (Figure 3). There are 72 seagrass species globally, and you can find them on this website. Pick your favorite seagrass and raise awareness of the importance of seagrass with your friends and family.

• Next, you can help protect seagrass and dugongs by looking after the ocean. An easy way to do this is by recycling, reducing single-use plastics (like water bottles and food containers), and by putting rubbish in the bin.

• You can also celebrate World Seagrass Day on March 1 each year. This day helps to raise awareness of how important seagrasses are and what activities threaten their health and survival.

• Finally, you can find local researchers or protectors and help them save seagrass. The good news is that there are a lot of them, and they may have community projects you can get involved in. Check out Project Seagrass, Seagrass Watch, and the World Seagrass Association as good places to start learning.

- Figure 3 - “Dugong detective” examining different seagrass species to choose its favorite!

Glossary

Indigenous People: ↑ Communities consisting of the original inhabitants of a region, with strong cultural ties to the local land and sea and many stories and experiences about changes in the land over time.

Birth Rate: ↑ The rate at which a species produces babies. Birth rates can be used to understand how quickly a species can recover, which can help us know if a species needs protecting.

Rhizome: ↑ A section of a plant that runs along the ground or sediment, connecting the roots and leaves together. Rhizomes can store energy made through photosynthesis, which can be used in times of stress.

Photosynthesis: ↑ The process plants use to make their own food (sugars) using carbon dioxide, water, and the energy of sunlight.

Positive Feedback Loop: ↑ A process in which a change causes effects that make the change grow even more, like a snowball rolling down a hill and getting bigger.

Genetic Diversity: ↑ A range of different features that can be passed from parents to offspring. An example is different eye colors in humans.

Tropical Cyclone: ↑ Is a circular storm that forms over warm oceans. This can bring strong winds and heavy rain.

Indicator Species: ↑ A species that can provide scientists with information on ecological changes simply based on their presence. This can give scientists an indication on the health of an ecosystem.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding for comissioned Figures 2 and 3 was provided by Edith Cowan University.

References

[1] ↑ Marsh, H., J, O’Shea., and T, E. Reynolds III. 2011. Ecology and Conservation of the Sirenia: Dugongs and Manatees. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139013277

[2] ↑ Orth, R. J., Carruthers, T. J. B., Dennison, W. C, Duarte, C. M., Fourqurean J. W., Heck, K. L., et al. 2006. A global crisis for seagrass ecosystems. Bioscience 56:987. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[987:AGCFSE]2.0.CO;2

[3] ↑ Marsh, H., Grech, A., and McMahon, K. 2018. “Dugongs: seagrass community specialists”, in Seagrasses of Australia, eds. A. Larkum, G. Kendric,k G., and P. Ralph (Springer International Publishing), 629–661.

[4] ↑ Hobbs, J-P. A., Frisch, A. J., Hender, J., and Gilligan, J. J. 2007. Long-distance oceanic movement of a solitary dugong (Dugong dugon) to the cocos (Keeling) islands. Aquat Mamm. 33:175–178. doi: 10.1578/AM.33.2.2007.175

[5] ↑ Gales, N., McCauley, R. D., Lanyon, J., and Holley, D. 2004. Change in abundance of dugongs in Shark Bay, Ningaloo and Exmouth Gulf, Western Australia: evidence for large-scale migration. Wildl Res. 31:283–290. doi: 10.1071/WR02073

[6] ↑ Hays, G. C., Alcoverro, T., Christianen, M. J. A., Duarte, C. M., Hamann, M., Macreadie, P., et al. 2018. New tools to identify the location of seagrass meadows: Marine grazers as habitat indicators. Front Mar Sci. 4:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00009