Abstract

In many places in the world, there are communities of Indigenous Peoples—the first Peoples that inhabited those lands. Each community has its own unique history, culture, practices, spiritual beliefs, and worldviews. I work as a psychologist in Indigenous Peoples’ communities in northern Canada, exploring how we can use scientific methods, combined with the traditional wisdom of communities and culture, to improve mental health. In this article, I will tell you about Indigenous Peoples, how many view health and wellness, and what I do to support their mental health—specifically with groups of young people who are having trouble with substance use. I hope that this article will inspire you to find ways to combine scientific approaches with traditional wisdom, to improve your own wellbeing.

Dr. Christopher Mushquash won the 2023 Canada Gairdner Momentum Award for mental health and substance use research performed in close collaboration with Indigenous communities. This research is assisting the development of services for Indigenous children, adolescents, and adults, that suit the culture and context in which they live.

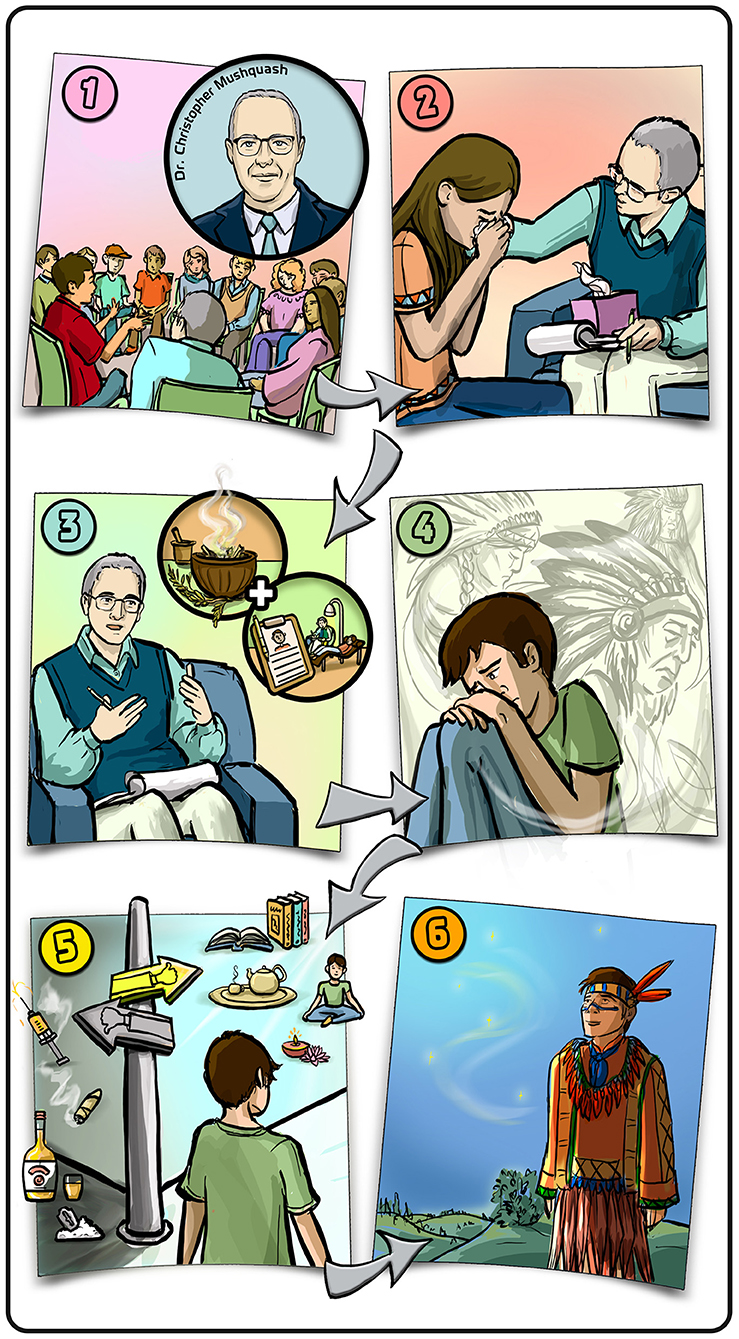

- Graphical Abstract - Article Summary.

- (1) My work with Indigenous communities is based on relationships—cooperation, trust, and a shared vision. (2) I meet Indigenous Peoples in my clinic and try to deeply understand their experiences. (3) The healing practices I offer my patients combine ancient wisdom (such as traditional ceremonies) and modern psychology techniques (such as questionnaires). (4) In one study, we found that some Indigenous Peoples are having trouble with substance use, because of trauma. (5) Understanding the source of their challenges empowers young people to heal and learn positive coping behaviors. (6) I encourage youth to: know who you are and where you came from, and lean on the things that bring you strength. Illustration by: Iris Gat.

Who Are Indigenous Peoples?

Do you know who lived on the land you live on 1,000 years ago? Or 5,000 years ago? There are three broad groups of Peoples that have been living in Canada (where I live), for thousands of years. These groups are called First Nations, which is the group I come from (Figure 1A); Inuit, who are the original inhabitants of the northernmost parts of Canada (Figure 1B); and Métis, who have a distinct culture with combined ancestry of both First Nations Peoples and European settlers (Figure 1C). Collectively, these groups are called Indigenous Peoples. According to the government of Canada, Indigenous Peoples is “a collective name for the original Peoples of North America and their descendants.” In other words, Indigenous Peoples are considered the first people who inhabited the lands that make up many of the countries that exist today. In Canada, there are Indigenous Peoples who live in urban centers and there are Indigenous Peoples who live in smaller, rural communities. Some Indigenous Peoples live in remote communities that are only accessible by airplane, or accessible by roadway only in the winter when the lakes are frozen!

- Figure 1 - Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

- In Canada, there are three main groups of Indigenous Peoples: (A) First Nations, (B) Inuit, and (C) Métis. Illustration by: Iris Gat.

Indigenous Peoples have very distinct histories, cultures, languages, practices, spiritual beliefs, and worldviews. What is shared between all the Indigenous Peoples in Canada is a history of colonization, in which people from Europe came to settle in Canada. As part of colonization, a lot of the traditional cultural practices of Indigenous people were disrupted. Some cultural practices were made illegal, and Peoples were physically threatened or harmed for engaging in them. This contributed to some of the mental and emotional health difficulties that Indigenous Peoples in Canada are now experiencing [1]. A big part of my work is to become familiar with Indigenous Peoples’ stories, cultures, and practices, and to find new ways to contribute to their mental health.

Wholistic Mental Health

Many non-Indigenous communities in Canada often think about health functionally, as simply being free from any type of physical illness. In contrast, for many Indigenous Peoples, health is understood in the context of being well, or having a sense of wellbeing in all aspects of human experience. Many Indigenous Peoples, including myself, view health and wellbeing as keeping a balance between the mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual areas of our lives. We also include social and environmental factors as part of health. In other words, we believe that people’s health is also determined by life circumstances, including education and income, whether they can regularly access enough healthy food and clean water to drink, what kinds of spaces they live in and whether their housing is enough for them and the other people they live with, and whether their physical environments are polluted. These are broad understandings of health, which Indigenous Peoples have held for hundreds to thousands of years, and these understandings are now spreading to non-Indigenous communities—and I am glad for it.

The focus of my work is mental health. I try to understand how we can use culture-based approaches—approaches that honor the cultural wisdom, knowledge, and practices—to help address current mental health and substance use difficulties faced by some Indigenous Peoples [2]. A big part of my work is to try to understand how to combine my knowledge and training in psychology with traditional practices and customs, to best benefit the health of Indigenous Peoples and communities. To do so, I must understand the bigger context of how each community views health in general, and mental health in particular, and I must be familiar with the common practices and ceremonies held in that community. This knowledge, along with a close relationship with the Indigenous community, helps me to come up with new ways of harmoniously weaving contemporary approaches and practices into the practices traditionally used by that community, to give people more tools with which to address their mental health difficulties.

How I Work With Indigenous Peoples

When I conduct a new study with Indigenous Peoples, I work very closely to understand their values. This helps me to develop trust and make sure that our goals are aligned. I then take the shared wisdom from both modern psychology and Indigenous culture-based methods, and collaborate with partners from community to generate research questions for mental health studies, such as how can we help young Indigenous Peoples in your community to regulate their emotions? Finally, I use my findings to improve wellness, to promote the use of certain practices and treatments, or to demonstrate how things might work differently and why that might be the case.

I am fortunate to work in a psychology clinic that is part of a community-based organization. This means that I work with the local community, and I learn about peoples’ needs, priorities, and experiences. I do my best to understand people as deeply as I can and shed light on their experiences based on my clinical training and knowledge. Often, direct exposure to people’s experiences helps me to get a general idea of the common difficulties that many people in that community are experiencing. Then I can use current, science-based psychology tools to offer a new service that could help people while also respecting their cultural beliefs and practices. Finally, I evaluate how effective the services are, for example by asking the people to fill out questionnaires (some of which we have developed in collaboration with people from the community!) report on whether the new treatment helped them to deal with their difficulties [3]. I also collect data using sharing circles, where I hear stories that people communicate about their experiences and the meaning a specific treatment has for them.

Helping Young People Deal With Substance Use Difficulties

My colleagues, students, and I are working on a study with First Nations Peoples who are having trouble with substance use [2]. We wanted to understand the role of adverse childhood experiences, which are difficult, sometimes traumatic experiences that people have in childhood. Scientists have studied adverse childhood experiences since the 1990s, but this type of work has not typically been done in close collaboration with First Nations Peoples. So, our close relationships and collaboration with the First Nations community is unique and significant.

In this study, we also wanted to understand the effects of colonization and intergenerational trauma on the experiences of young children (Figure 2). Intergenerational trauma is trauma that has been passed down through the generations. When European settlers came to Canada and cultural practices of Indigenous Peoples became disrupted, it negatively affected mental wellbeing. We found various connections between colonization, intergenerational trauma, and the disruption of relationships between children and parents. When early attachment is disrupted through colonial processes, children’s abilities to regulate their emotions and control their impulses can also disrupted. This can lead to an increase in the risk that an individual experiencing emotional challenges might use substances to manage those difficult feelings. We also found that the difficulties First Nations Peoples experienced through childhood were, on average, larger than the difficulties experienced by non-Indigenous Peoples, due to the intergenerational trauma that resulted from colonization. Finally, we found that, unfortunately, such difficult experiences are increasing in some First Nations communities.

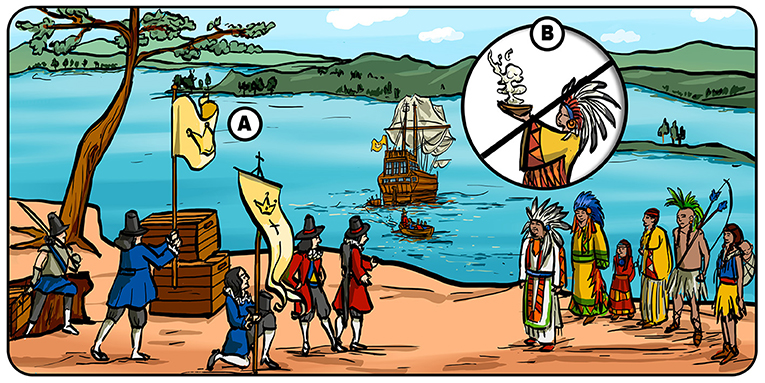

- Figure 2 - Intergenerational trauma and substance use.

- Substance use problems in young Indigenous Peoples can be rooted in intergenerational trauma. This trauma interferes with emotional development in childhood, making it more difficult to manage difficult feelings in adolescence. (A) Much of this trauma resulted from colonization. (B) The traditional cultural practices of Indigenous Peoples were disrupted, and in some cases outlawed, which continues to have negative impacts on the wellbeing of the community for generations. Illustration by: Iris Gat.

To support young Indigenous Peoples in dealing with substance use, we developed ideas from psychology to include specific difficulties experienced by First Nations Peoples. Then we worked with the First Nations Peoples who experienced these difficulties to develop new understandings about how to cope with trauma and the challenging emotions they might experience. This kind of understanding gives Individuals the power to develop new skills that can have positive effects on their health. We also help people to learn about how emotional injuries from past trauma can be healed by cultural practices. For example, people who are trying to regulate their emotions and deal with difficult past experiences might be helped by participating in cultural and spiritual practices like sweat lodges or smudge ceremonies. These traditional practices can help people to process what they have experienced and help them to focus on the current moment—which can help them to regulate their emotions and lead to new ways to manage strong feelings in difficult moments.

I am happy to say that I am hopeful about the future. I think that there is more national and international attention on Indigenous Peoples’ mental health and wellness today than there has ever been before. Many people in our communities are working to improve the mental health of Indigenous Peoples, including Elders, cultural teachers, community members, health professionals and researchers; and many young people who are joining these professions have a lot to contribute. My vision for the future is that the next generations of young scientists and clinicians (like you!) will be confident in their ability to help answer questions that are important to Indigenous Peoples. This career is very meaningful to me, and I believe many young Peoples will find it incredibly meaningful as well. Whichever route you choose along your life’s path, remember who you are and where you came from, and lean on the things from your own unique background and experience that bring you strength.

Glossary

Indigenous Peoples: ↑ The original inhabitants of an area.

Colonization: ↑ An act in which settlers seek control over the Indigenous Peoples of an area and the lands they inhabit.

Culture-Based Approaches: ↑ These are techniques that are rooted in the cultural wisdom of the community that the psychologist is working with.

Substance Use: ↑ The use of substances, such as drugs, tobacco, or alcohol, that could have negative effects on the person and/or the people around them.

Adverse Childhood Experiences: ↑ Difficult experiences that people had in childhood, that might have effects on health and wellness in adult life.

Intergenerational Trauma: ↑ Emotional challenges, or traumatic experiences, that are passed between generations—through families.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional Materials

- Dr. Christopher Mushquash—2023 Canada Gairdner Momentum Award.

- 2023 Canada Gairdner Momentum Award Laureate: Dr. Christopher Mushquash (YouTube).

- Dr. Mushquash Live Q&A-2023 Canada Gairdner Awards—Advice for Young Scientists.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Noa Segev for conducting the interview which served as the basis for this paper and for co-authoring the paper, and Iris Gat for providing the figures.

References

[1] ↑ Nelson, S. E., and Wilson, K. 2017. The mental health of Indigenous Peoples in Canada: a critical review of research. Soc. Sci. Med. 176:93–112. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.021

[2] ↑ Rowan, M., Poole, N., Shea, B., Gone, J. P., Mykota, D., Farag, M., et al. 2014. Cultural interventions to treat addictions in Indigenous populations: findings from a scoping study. Subst. Abuse. Treat. Prev. Policy. 9:1–27. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-9-34

[3] ↑ Fiedeldey-Van Dijk, C., Rowan, M., Dell, C., Mushquash, C., Hopkins, C., Fornssler, B., et al. 2017. Honoring Indigenous culture-as-intervention: development and validity of the Native Wellness AssessmentTM. J. Ethn. Subst. Abuse 16:181–218. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2015.1119774