Abstract

The economy is what keeps the world as we know it functioning. Our daily lives are heavily affected by the economy, both locally and globally. Some people think that the economy is mostly concerned with money, but in fact it is much broader than money. The economy relates to very fundamental issues concerning human life, such as human wellbeing and equality between people and groups. In this article, I will give you a taste of the ways in which economists view human wellbeing. I will then explain why, when we study the economy, it is not enough to look only at individuals or at groups of people—we need to do both. Finally, we will discuss the future of the economy, and I will share some tips that I have learned during my scientific career.

Professor Angus Deaton won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2015 for his analysis of consumption, poverty, and welfare.

What Is the Economy

The economy is one of the pillars around which our world revolves, that affects us individually and collectively. The economy was not designed by someone for a certain purpose—it is a complex, dynamic phenomenon that is generated by the activity of individuals trying to make themselves better off. The economy changes over time and does so quite rapidly, especially in the last 20–30 years. Current and ongoing advances in technology, along with increased globalization, profoundly change the ways in which the economy operates. All these factors make economics a complex field of study (to learn more about economics, see here).

Our job as economists is to uncover some basic principles that influence economic activity (human greed is one of them!). We try to identify relationships between various aspects of the economy, such as relationships between how much money people make, how much products cost, which kinds of products are being purchased and how much of them, and how much money people are saving. In microeconomics we ask questions about the individual economic choices that people make. In parallel, we can also ask questions on a larger scale about how economic choices of large groups (such as countries) affect the economic state of the whole group. These broad questions are dealt with in the field of macroeconomics.

Ideally, our understandings of both micro- and macro- economics are developed into useful policies and regulations that make people better off. Luckily, economics has become a much more data-driven science over the last few decades, so economists can now use the huge amount of data they have collected to gain new insights about various economic processes that were previously difficult to understand or impossible to study.

As you will see throughout this article, economics is not just about money—it deals with fundamental issues of human wellbeing, inequality, and poverty. The ways that we view and act upon these issues can influence the welfare of individuals and of society as a whole. I have dedicated my career to studying these critical issues, and I now invite you on a journey that will give you a glimpse into some of my important findings.

Economy and Human Wellbeing

Economists have been accused of being interested only in money and in how financially well-off people are, but that is only a small part of economics. Many economists think about human happiness and wellbeing. Amartya Sen, an Indian economist who is a hero of mine, likes to think about economic wellbeing by asking what kinds of things people are capable of doing, given their circumstances, including their money. According to Sen, a person’s quality of life and wellbeing have to do with how able are they are to do the things they would like to do to—things that make life worth living [1]. This capability is influenced by many life conditions, including a person’s health and where they live. Poverty is broader than simply not having enough money—it is the inability of a person or group to achieve the level of functioning that they value. Poverty is therefore concerned with health, education, jobs, and protection from violence, among others.

What if we think about a successful economy as one that increases human happiness? Jeremy Bentham was an influential economist who believed in that approach. But, simply asking people how happy they are is problematic because there are different kinds of happiness. A study I did with Prof. Daniel Kahneman, a fellow Nobel Laureate in economics, revealed that overall life satisfaction is different from feeling happiness in a given moment [2]. Imagine yourself having a great time with your friends at the movies. If I were to ask you how happy you are, you might say that you are very happy. But if I were to ask you how your life is going, you might say that it is not going so well, because you are having trouble at school and you do not like where you are currently living. Does that mean that you are happy or not? Or, if you have been intensely studying for an important exam all week, you might say that you are not so happy right now. But, if I were to ask you how your life is going overall, you might say that it is going very well, and that you are enjoying your studies and your social life.

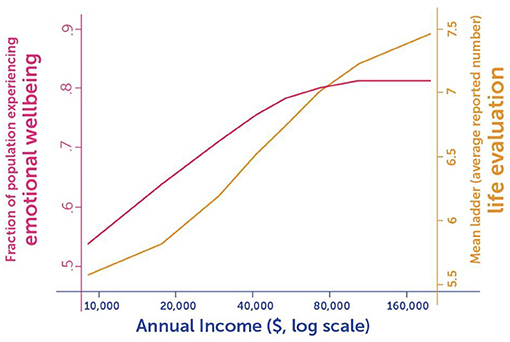

Our study showed that above a certain yearly income (about $75,000 U.S. in 2010), an increase in income does not increase happiness (Figure 1). We believe this is so because beyond this income, the ability of individuals to do what matters most to their emotional wellbeing does not increase. On the other hand, life evaluation (satisfaction) keeps rising with increasing income. In other words, people feel more satisfied with their lives as their income increases, such that every doubling of income results in the same increase in their life satisfaction. Therefore, in economics it is important to distinguish between types of happiness to take them all into account.

- Figure 1 - Momentary happiness and life satisfaction are different.

- Momentary happiness, represented here as a measure of emotional wellbeing (pink line), stops increasing at a certain income level (around $75,000 U.S. in 2010). Life satisfaction, represented here as a measure of life evaluation (yellow line), keeps rising as annual income increases. This shows that there are multiple aspects to happiness, and that they act differently in response to life events (figure adapted from Gotoh and Dumouchel [3]).

The topic of human wellbeing is complex—it is challenging to define it, measure it, and turn our results into effective economic policies and regulations. With time, I believe we will gain a clearer understanding of the aspects that contribute to human wellbeing, which will help us direct the economy to maximize human wellbeing.

Wellbeing—Individuals Versus Large Groups

The average economic behavior of groups of people is very different from the behavior of the individuals who make up these groups (Figure 2). The interactions between people (and other economic players, such as companies) are important. An understanding of only the way people (or other players) work as individuals may not explain how they act when they form groups.

- Figure 2 - The economic behavior of groups of people is different than that of individuals.

- When we want to see the full economic picture, we must consider both the average economic behavior of groups of people (middle), and the economic situation of individuals, or sub-groups, within the larger group (four surrounding circles).

As an example, let us say that I am a farmer and I have a really good crop this year. When I bring my harvest to the market, I think “Wow, this is great! I am going to be rich this year!” But it turns out that many other farmers had great crops too, and, as a result, the price of the crop drops so much that I actually become poorer (Figure 3). This is a simple example of what happens when we look at the combined result of many individual actions—we often see something very different from what we see at the individual level.

- Figure 3 - The economic picture for individuals can be different from that of large groups.

- (A) When there is a good year of corn crops, individual farmers expect a large profit. (B) However, many other farmers also experienced good corn crops. (C) Because there is so much corn available, the price of corn actually goes down and the farmers will get less money for the same amount, and might even finish up making less money in total, in spite of their larger crop.

On the other hand, it is not enough to look only at what is happening on average—we also need to look “under the hood" at what is happening at the individual level and for specific groups of people. For example, my colleague Anne Case and I showed that almost all the gains in the gross domestic product (GDP) in the United States since 1970 have gone to only one third of the American population—people who have at least 4-year college degrees [4]. The other two thirds of the population—people without college degrees—have not benefited from gains in GDP. This means that to know if Americans are better off following an increase in GDP, we must “zoom in” on specific groups of people, and even down to individual people, to figure out how well they are doing.

In summary, to understand economics in general, and human wellbeing in particular—we must look both at the individual level and the aggregate level. Only the integration of both perspectives can give us a complete picture of any given situation. As you saw, the economy deals not just with money, but with much broader questions about how to make people better off and improve their overall quality of life.

Recommendation for Young Minds

My first piece of advice to the young scientists among you is: do not be afraid to go off in a different direction from everyone else. Part of conducting great science relies on each scientist contributing their unique perspective and way of thinking. Even if your peers and colleagues do not accept your views, stay true to your personal way, and know that good things might come out of it in the future.

When it comes to choosing an occupation, it is good to follow your passions—but within reason. Choose something that is both important for you personally but that benefits others as well. For example, devoting your life to dealing with climate change seems to me like a reasonable thing to do in today’s world. Although such a path will not always be pleasant and easy, you will be satisfied and pleased with yourself when you learn something new about the world and implement it to help your environment.

For those who will choose an academic career, I recommend that you first gain a strong academic background in one selected discipline, before exploring other useful disciplines. Be aware that mathematics is important for many career choices. It helps scientists and economists develop models and theories and, on a more basic level, it helps to ensure that we are thinking straight and avoiding unnecessary errors.

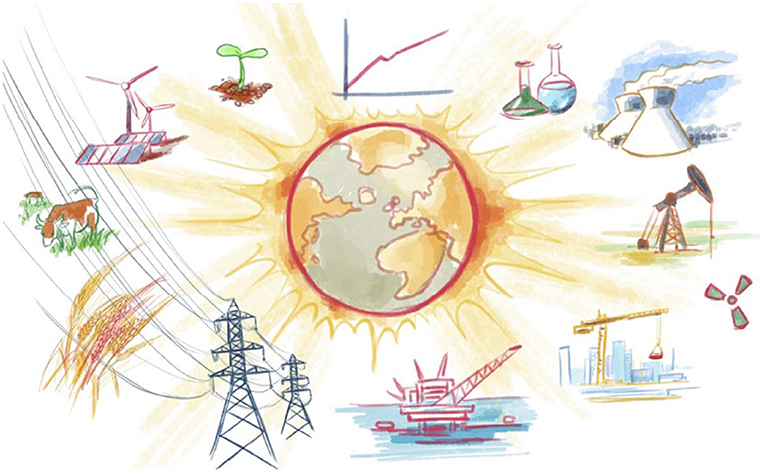

Finally, kids of your generation should hold us—the grown-ups—accountable for the kind of world we will leave for you. Do not tolerate receiving a destroyed planet (Figure 4). If we adults deplete the planet through our irresponsible behavior, you and your kids will have a more difficult future. There are already many things we can do to save our planet from further damage, and we must find ways to implement those steps as soon as possible. The choices we make now will influence the generations of the future. Your role is to drive these actions forward—help the older generation to make the right decisions today, to make sure that your generation and those that follow will be able to live a good life on this planet.

- Figure 4 - The planet’s future is in our hands.

- The choices we make in our everyday lives about the energy sources we use, how we use our land, how we produce our food, and the processes we employ in our industry and agriculture, profoundly affect our present and future lives on this planet. Young people should hold grown-ups accountable for the condition of the world they leave behind and help adults make choices that will lead to a better future for the generations to come.

Glossary

Globalization: ↑ The increasing influence that people and companies that are far apart (even across the globe) have on one another.

Economics: ↑ A social science that focuses on human wellbeing, focusing to a large extent on the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services, and that analyzes the choices individuals, businesses, governments, and nations make regarding their resources. It is also concerned with distribution between people, and on poverty.

Microeconomics: ↑ The study of the economic behavior of individuals, such as consumers, companies, and industries.

Macroeconomics: ↑ The study of the entire economy, including the general behavior of prices and the total amount of products and services present.

Life Satisfaction: ↑ A subjective measure of how your life is going.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP): ↑ A measure of how a whole country is doing financially. It is the total value of the products and services produced in a country over 1 year.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Noa Segev for conducting the interview which served as the basis for this paper and for co-authoring the paper, and Alex Bernstein for the illustrations.

Additional Materials

- The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality—a book by Prof. Angus Deaton on the history of economic development and how it influences our health and living standards.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Sen A. 2003. “Development as capability expansion,” in Readings in Human Development, ed S. Fukuda-Parr (New Delhi; New York, NY: Oxford University Press).

[2] ↑ Kahneman, D., and Deaton, A. 2010. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:16489–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011492107

[3] ↑ Gotoh, R., and Dumouchel, P. 2009. Against Injustice: The New Economics of Amartya Sen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[4] ↑ Case, A., and Deaton, A. 2021. Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.