Abstract

Staying healthy is an important priority—but why is being healthy so important to you? It is because, when your body is healthy, you can do the things you want to do. We call this dimension of health functioning, and it results from complex interactions between biological health and a person’s external environment. If we want to include functioning in our definition of “health” so that it can be used in all fields of healthcare and research, we need a common set of terms and a shared set of methods for measuring human functioning. This article explains the concept of functioning and how this concept allows us to fully understand health—both the health of individuals and of the overall population. We will discuss how functioning can be measured by health professionals and describe an exciting new field, called human functioning sciences, that can open the door to a revolutionary approach to health and wellbeing. We will also provide an example of how functioning could be integrated into the healthcare system to improve patients’ experiences.

What Does It Mean To Be Healthy?

Many of us work hard to keep ourselves healthy. We try to exercise, eat balanced meals, and visit the doctor regularly. Doctors and scientists all over the world spend their lives developing treatments and cures for diseases and researching the effects of our lifestyle choices on our biological health—the health of our bodies and minds. Obviously, good health is a priority for both individuals and societies.

For many years, global organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations (UN) have monitored biological health of people all over the world, by collecting two main measures of health information: morbidity and mortality. These are related but separate concepts. Morbidity refers to having a disease or any condition that is not healthy—like cancer, COVID-19, depression, or obesity. It also refers to the amount of disease in a population. For example, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that 41.9% of people in the US were characterized as obese between 2017 and March 2020 [1]. Mortality refers to the number of deaths that occur from a specific illness or condition. For example, the CDC reported that about 697,000 people in the US died from heart disease in 2020 [2]. People can have more than one morbidity at once, and morbidities might not result in mortality unless they worsen over time.

While morbidity and mortality are clearly useful measures of health and can teach us a lot about many diseases and human health challenges, do they really capture everything it means to be healthy? We think there is more to the story, and the rest of this article will describe that additional element.

What Is Missing?

Think about why your health is so important to you. It is probably because, when you are biologically healthy, you can do the things you want to do—the things that make your life worth living! Feeling satisfied with your life because you can work toward—and hopefully achieve—your life goals contributes to your wellbeing. While it seems obvious that biological health is an important part of wellbeing, do indicators of morbidity and mortality alone explain your degree of wellbeing? This would imply that doctors could improve peoples’ wellbeing just by helping them to live longer lives and decreasing the amount of suffering they experience due to diseases, injuries, and other health conditions. But it is not that simple. Sometimes, a person may be perfectly healthy, yet other factors, including the conditions of their environments, might make it hard for them to do things that contribute to their wellbeing. Perhaps the air where they live is polluted, so it is difficult to spend time outdoors; or maybe they lack access to formal education or other social benefits that would help them to thrive [3]. Having a secure job, finding good relationships, and living in a nice place—all things that can be impeded by the environment—directly contribute to wellbeing.

It seems, then, that the missing link between biological health and wellbeing has to do with our overall ability to function in our environments. The WHO recognized functioning as an important dimension of health in 2001, because it helps us to understand what health is and why it is important [4]. If we can measure functioning, perhaps we can get a fuller picture of the health of individuals and the welfare of society as a whole.

Functioning: The Lived Experience of Health

Functioning results from complex interactions between the states of our bodies and our external environments. Throughout our lives, most of us will (at least occasionally) experience pain, anxiety, weakness, tight joints, injuries, and other morbidities. But our lived experience of health describes the way these health issues actually affect our daily lives, often by preventing us from functioning as we would like or achieving our goals. For example, if we cannot climb stairs painlessly, walk as far as we used to, clean or dress ourselves, read a book, make and keep friends, do all the homework we need to do, or perform our jobs, then these real-life difficulties are the lived experiences of our health issues. While most public health systems are good at collecting data on morbidity and mortality, measuring whether people are functioning effectively is much more difficult. There are so many unique examples of functioning in people’s daily lives—how can public health officials accurately assess them?

To help scientists, doctors, and public health officials measure health and disability at both the individual and population levels, the WHO created a system called the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in 2001. This framework helps health professionals learn how to describe, organize, and measure information about functioning, and it provides a standard language that allows data on functioning to be compared widely, even between countries [5].

Lessons From Rehabilitation

Applying a description of health that includes functioning will be easier for some fields of healthcare than others—it is a new way of thinking for many areas of medicine. For example, the field of infectious disease tends to focus on finding the organisms that cause diseases and discovering ways to prevent or treat those diseases. Because they are so busy finding causes and treatments, infectious disease doctors and researchers might not spend as much of their time thinking about how a disease, like COVID-19 or diabetes, affects a patient’s lived experience, or how they could maintain or improve the functioning of someone suffering from a certain disease. On the other hand, some fields already focus on functioning and can serve as models for the rest of the medical community. The health strategy of rehabilitation is the best example. Rehabilitation is a field of medical practice that helps people regain functions they have lost due to injury or illness. For example, rehabilitation can help people use one of their limbs again after an injury, or help people regain brain function after a stroke or concussion. Rehabilitation professionals have long recognized the importance of functioning for health and wellbeing, so they already have ways to measure functioning and a common language to describe it—terms like “functional loss” and “functional limitation.”

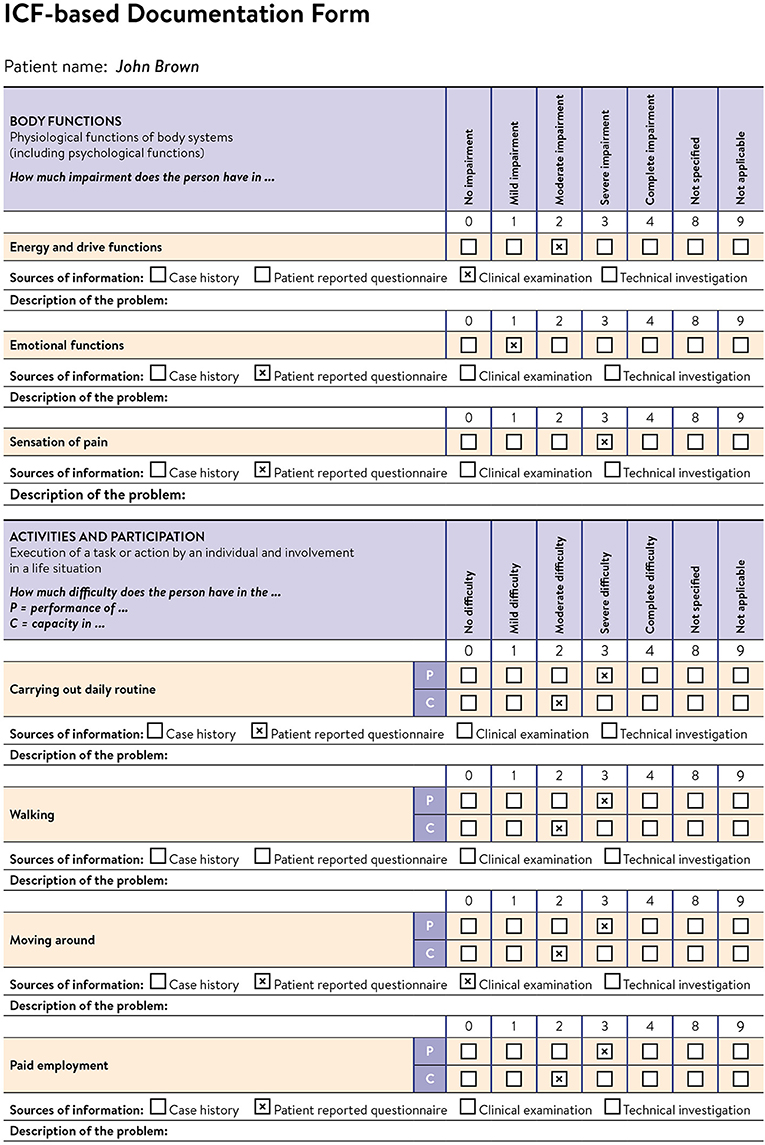

To be useful at all levels of the health system—from doctors, nurses, therapists, and technicians all the way up to global health agencies—health information must be reliable and comparable. That means data on functioning must be measured in accurate ways so that it is trustworthy, and that those forms of measurements should be similar across all fields of healthcare everywhere. When measurements of functioning are standardized in this way, functioning data collected by, for example, rehabilitation professionals in one country could be understood by (and compared to) functioning data collected by heart doctors in a different country. Functioning could be assessed using a standardized set of questionnaires, instruments, or measurements (Figure 1). The ICF is widely used in the development and testing of measurement instruments and questionnaires.

- Figure 1 - An example of a form that could be used to assess human functioning.

- This form is based on the ICF and was developed by the ICF Research Branch. When shared methods to accurately measure human functioning exist, they allow experts across fields and in separate countries to compare and understand each other’s functioning data.

For information on functioning to be comparable, it is also necessary for all fields of medicine and research to “speak the same language” when it comes to functioning. When health professionals use a common set of terms, they can more easily understand each other and ensure that they are talking about the same thing. As we mentioned earlier, the WHO’s ICF provides such a language to help health professionals communicate about functioning. The shift to a common language is challenging—it takes money and time. Governments and other organizations that manage health systems will need to help those systems obtain the money and technical support needed to make these important changes.

Healthy Individuals Create Healthy Societies

Understanding health in terms of functioning also clarifies why healthy individuals help to improve the welfare of an entire society. Unhealthy people often miss work, either because they do not feel well or because they cannot function properly in their work environments. When many individuals in a society can live up to their potentials because they are biologically healthy and function well, there will be more people in the workforce. This can lead to increased production of goods and services and long-term economic prosperity for the whole society.

When we look at it this way, it seems obvious that investing money and resources into health and healthcare—and making sure those resources are spread equitably across all regions of the world—is a good idea for everyone! Thinking of health and wellbeing in terms of functioning also gives us another important insight into healthcare. Traditionally, healthcare has been viewed as separate from other fields, like environmental protection or the provision of certain public services. But if living in a pleasant, unpolluted environment and having access to things like, for example, public transportation or free education improves our wellbeing, are these areas not ultimately important determinants of human health, too? Rethinking health in terms of functioning could potentially help us to bridge many important, formerly separate issues, which could have major benefits in terms of individual and societal wellbeing.

Human Functioning Sciences—A New Scientific Field

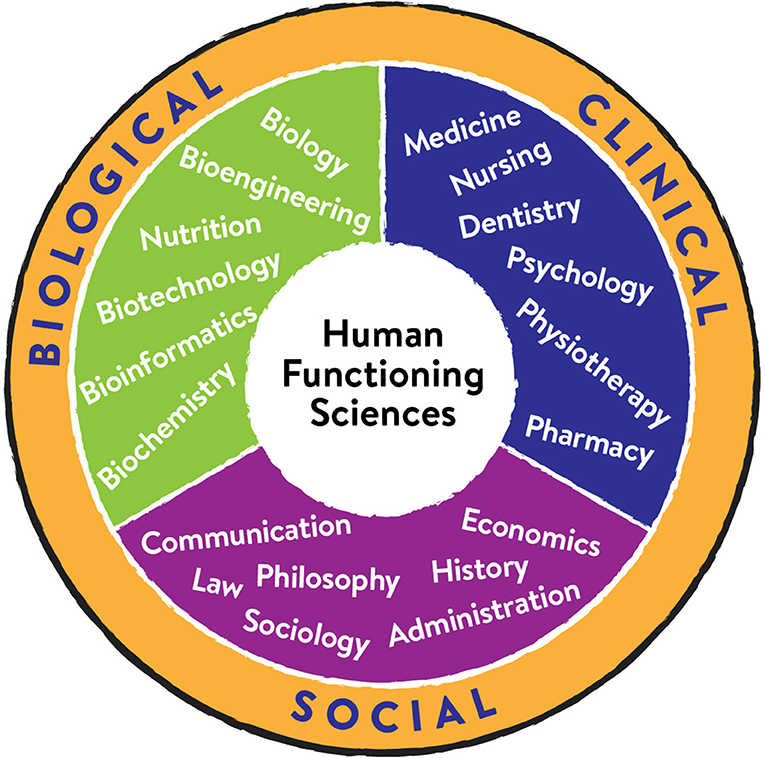

Incorporating functioning into the definition of human health is generating a new, emerging field of study and practice called human functioning sciences [6]. This is an interdisciplinary field, which means that it combines knowledge and methods from multiple other scientific disciplines that are usually kept separate (Figure 2). The aim of human functioning sciences is to understand people’s lived experiences of health, to explore the links between health and wellbeing, and to help societies understand and improve the connection between individual healthcare, the health of all people, and the welfare of the society as a whole. Human functioning sciences can provide a big-picture to look at human health, in terms of all the aspects of our lives and environments that can affect human functioning. Human functioning scientists would work to improve both an individual’s biological health and his or her performance in a given environment, including possibly making changes in the environment to better accommodate the individual’s needs.

- Figure 2 - Human functioning sciences is an emerging interdisciplinary scientific field that studies human functioning.

- Interdisciplinary means that it combines knowledge and methods from other scientific disciplines rooted in the biological, clinical, and social sciences. Such a broad field provides a big-picture assessment of the health of both individuals and societies.

Functioning Information Can Help With the Cost of Healthcare

Healthcare systems started including information about functioning years ago, but these systems are complex and involve many levels of decision making, so changing the way they describe health is not easy and will require some time. A good example of how functioning information might ultimately help patients and healthcare systems involves the financing of healthcare—in other words, how it is paid for. Often, patients are reimbursed for their health expenses by insurance companies, or government healthcare plans pay for citizens’ health-related expenses. Many health systems rely on reimbursement schemes that classify patients by disease type, which helps to organize and plan the type of care patients should receive or be reimbursed for. However, people with the same diseases can have different characteristics and may need different services—a disease does not look the same in all patients. Information on functioning can tell healthcare systems about the specific needs of individual patients, which will improve patients’ treatments and help both patients and health systems to spend their money more wisely.

Conclusion

Good health is an important priority for people all across the world—so much so that one of the goals supported by the United Nations is “to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all ages” [7]. The traditional use of morbidity and mortality to describe human health was clearly missing a component. After all, living a long time is not necessarily living well—data suggest that living longer can actually mean living in worse health [8]! Also, while the absence of disease and injury may be necessary for human flourishing or societal welfare, it is not enough. Functioning—a concept to describe both biological and lived health—provides the missing link. The addition of functioning as an essential component of health gives us a more complete and meaningful definition of health and explains both how individual health contributes to wellbeing and how the health of an entire population contributes to the welfare of the whole society.

Glossary

Biological Health: ↑ The health of the body and mind.

Morbidity: ↑ Refers to having a disease or any condition that is not healthy. Also refers to the amount of disease in a population.

Mortality: ↑ The number of deaths that occur from a specific illness or health condition.

Wellbeing: ↑ The state of feeling happy and satisfied with life.

Functioning: ↑ All the things that people with a health condition can or cannot do in interaction with the world.

Lived Experience: ↑ What happens to people in their lives; the things they see, feel, and go through.

Rehabilitation: ↑ Field of medical practice that helps people optimize functioning lost due to disease or injury.

Human Functioning Sciences: ↑ A new field of scientific study and practice that aims to understand people’s lived experiences of health and to explore the links between health and wellbeing.

Interdisciplinary: ↑ Combining knowledge and methods from multiple fields that are usually kept separate.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Co-written by Susan Debad Ph.D., graduate of the University of Massachusetts Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (USA) and scientific writer/editor at SJD Consulting, LLC.

Original Source Article

↑Bickenbach, J., Rubinelli, S., Baffone, C., and Stucki, G. 2023. The human functioning revolution: implications for health systems and sciences. Front. Sci. 1:1118512. doi: 10.3389/fsci.2023.1118512

References

[1] ↑ Stierman, B., Afful, J., Carroll, M. D., Chen, T.-C., Davy, C., Fink, S., et al. 2021. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports 158, June 14. Available online at: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273 (accessed May 15, 2023).

[2] ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. Heart Disease Facts. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts.htm (accessed May 15, 2023).

[3] ↑ Stucki, G., and Bickenbach, J. 2019. Health, functioning, and well-being: individual and societal. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 100:1788–92. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.03.004

[4] ↑ Stucki, G., and Bickenbach, J. 2017. Functioning: the third health indicator in the health system and the key indicator for rehabilitation. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 53:134–8. doi: 10.23736/s1973-9087.17.04565-8

[5] ↑ World Health Organization. 2001. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

[6] ↑ Stucki, G., Rubinelli, S., Reinhardt, J. D., and Bickenbach, J. E. 2016. Towards a common understanding of the health sciences. Gesundheitswesen 78:e80–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-108442

[7] ↑ United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: United Nations. Available online at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed May 15, 2023).

[8] ↑ Chatterji, S., Byles, J., Cutler, D., Seeman, T., and Verdes, E. 2015. Health, functioning, and disability in older adults–present status and future implications. Lancet 385:563–75. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61462-8