Abstract

Do you think that eating fruit in summer has the same effect on your body as does eating it in winter? Scientific evidence says no. Fruits contain polyphenols, which are substances produced by plants in response to the growing conditions. When animals eat these fruits, polyphenols signal animals’ bodies to adapt to the seasons. For example, bears eat berries in late summer because these fruits provide essential substances needed during hibernation. It has been observed that the effect of these fruit substances is affected by biological rhythms, which are chemical cycles that animals’ bodies follow that vary throughout the year. Thus, eating fruit in- or out-of-season generates different effects in your body. Eating fruit in-season is associated with optimal health effects. Hence, we must eat fruits in-season so that the rhythms of our lives are synchronized with the seasons.

Do you think that eating a fruit in summer has the same effect on your body as does eating it in winter? Many of you will say yes, but some scientific evidence says no!

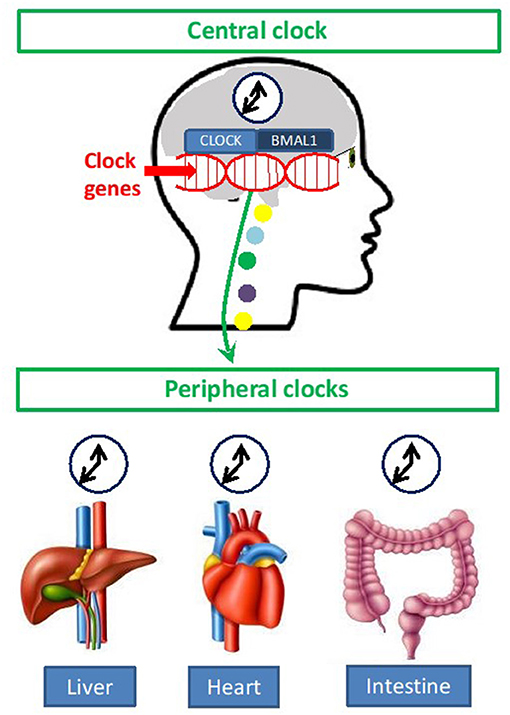

The activity of our cells, and the cells of other organisms, is not always the same—cellular activity changes depending on the time of day and the season of the year. Animals, including humans, have what are known as biological rhythms, controlled by internal clocks. In mammals, there is a central clock located in the brain, which produces two proteins (called CLOCK and BMAL1) that can join to form a complex (Figure 1). This complex interacts with the clock genes and activates them. The activation of clock genes creates several proteins that travel throughout the body and act as signals that regulate the functioning of the body’s cells. In addition to the clock in the brain, all the cells of the body have their own clocks (called peripheral clocks) that control the specific processes in each organ, such as in the liver or intestines. For example, at night we produce molecules that make us sleepy, helping us to rest and recover from the day and giving us energy for the following day.

- Figure 1 - The body’s central and peripheral clocks regulate its functions.

- In certain cells of the brain, the proteins CLOCK and BMAL1 join, forming a complex, which interacts with clock genes and activates them. The activation of the clock genes produces various proteins that travel to the peripheral clocks located in the organs including liver, heart and intestines. There, they act as signals that regulate the functioning of the body’s cells through correct synchronization of these organs.

How Does the Body Know What Time It Is?

The body sets the time of its cellular clocks using signals such as light. But as we all know, the number of hours of light per day is not the same over the entire year. Summer days have more hours of light than winter days, for example, due to the rotation of the Earth around the Sun. In response, our bodies have evolved to use light efficiently, adjusting our functions and behaviors to this rotation and adapting to the light changes.

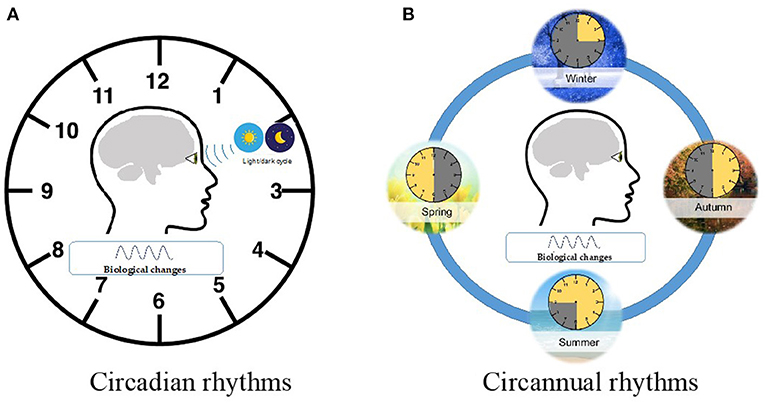

The activity of our cells follows two types of biological rhythms. Circadian rhythms explain how organisms organize their functions in 24-h cycles, while circannual rhythms are defined in 12-month cycles (Figure 2) [1].

- Figure 2 - Biological rhythms include (A) the circadian rhythm, which are natural 24-hours cycles physiology and behavior; and (B) circannual rhythms, which are natural 12-months cycles of physiology and behavior.

- Both types of biological rhythms can cause biological changes that regulate the organism.

In addition to light, which is one of the main signals that set our biological clocks, other important factors, such as nutrition, can also affect our biological rhythms. This means that what we eat can change the way our bodies function. For example, plants contain substances that, when eaten, serve as signals that regulate our clocks. The xenohormesis theory proposes that some of these plant substances provide our bodies with information about the environmental conditions in which those plants were grown, and these signals allow us to adapt to the various seasons of the year. In other words, this theory says that if we consume fruits and vegetables produced where we live when they are in-season, our bodies will be ready to make the changes required to face the upcoming season. For example, bears eat berries in late summer because these fruits provide them essential compounds needed during hibernation [2].

Plant Polyphenols Synchronize Biological Rhythms

Polyphenols are substances produced by plants that are good for our health—they help to prevent several diseases, such as high blood pressure and obesity. In addition, polyphenols can also affect biological rhythms. There are more than 8,000 different polyphenols [3], present in fruits, vegetables, cocoa, and beverages such as tea or wine. These compounds are produced by the plants in response to environmental stresses such as cold temperatures, rainfall, or drought. Therefore, each plant has a specific, unique polyphenol composition depending on the environmental conditions in which it was grown, and those polyphenols provide us with information about the environment during the plant’s growing season.

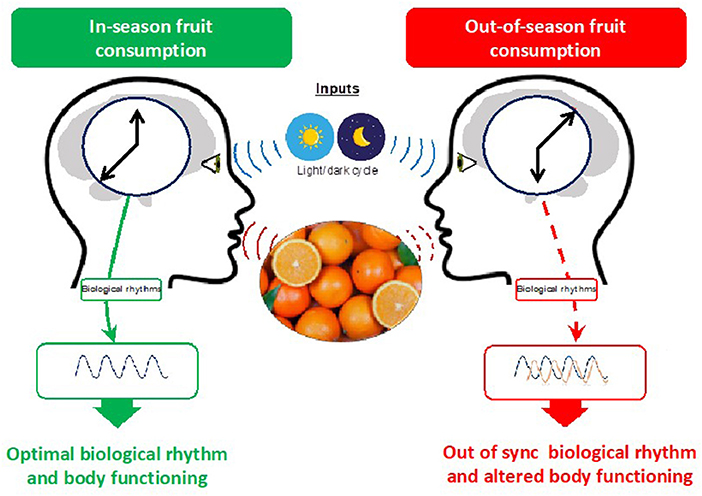

But today, all fruits and vegetables can be eaten throughout the whole year. For example, the orange, a winter fruit, is grown and harvested during the winter in South Africa, and can be eaten in Europe during the spring and summer. According to the xenohormesis theory, if a European eat this orange, he will receive “winter” signals and his body will prepare for winter. This can cause a conflict, or desynchronization, between his internal clock and the actual environment conditions (Figure 3).

- Figure 3 - Consumption of polyphenol-rich fruits in-season may cause improve body functions, by synchronizing correctly the biological rhythms.

- However, consuming these same fruits out-of-season may result in different biological responses [Adapted from [4]].

What Happens When I Eat Fruits Out-of-Season?

Chrononutrition is the field of research that studies the interactions between biological rhythms and nutrition. Using rats, our group has evaluated the effects of eating various fruits both in- and out-of-season. To do this, the rats were adapted to different periods of light and darkness, to simulate the seasons. These periods were either 6 h of light and 18 of dark, to simulate winter, or 18 h of light and 6 h of dark, to simulate summer. The rats were fed grapes, sweet cherries, tomatoes, and oranges. Our results showed that eating these fruits in-season enhanced the rats’ body functions, by acting on the liver, muscles, and intestines, among other organs [4]. Eating the same fruits out-of-season produced different biological responses [4]. For example, when rats ate grapes in-season (winter), their intestines absorbed more polyphenols than did the intestines of rats that ate grapes out-of-season (summer).

What Does This Mean for Me?

Since polyphenols provide health benefits, as mentioned earlier, the rats therefore obtained more health benefits from polyphenols when they consumed fruits in-season. This evidence is in line with the xenohormesis theory, and it suggests that we should eat fruits in-season, so that the rhythms of our lives are synchronized with the environment. However, it is still better to eat fruit out-of-season than not to eat fruit at all. Remember that eating five servings of fruits and vegetables (in- or out-of-season) per day is recommended but, according to our evidence, it is better to eat fruits and vegetables that are in-season.

Going back to our initial question, do you still think that eating fruit in-season generates the same effect as eating it out-of-season?

Funding

The Ministerio De Economía, Industria Y Competitividad (AGL2016-77105-R) funded this research and the European Union through the Operative program ERDF of Catalonia 2014-2020 (PECT-NUTRISALT). AA-A and FB are Serra-Hunter Fellows; AC-C and MR are recipient of a predoctoral scholarships to 2017PMF-PIPF-64 and 2018PMF-PIPF-20, respectively.

Glossary

Biological Rhythms: ↑ Biological rhythms are natural cycles of changes in chemicals or functions in our bodies. The biological rhythms work as an internal “clock” that coordinates the other clocks in our bodies.

Peripheral Clocks: ↑ Peripheral clocks reside in various tissues throughout the body, and allows organisms to optimize their behavior and metabolism to adapt to daily demands they face by tracking the time of day.

Circadian Rhythms: ↑ Circadian rhythms are daily cycles of physiology and behavior that are driven by an internal clock with a period of approximately (circa-) 1 day (dies).

Circannual Rhythms: ↑ Circannual rhythms are long-term (tau ≈ 12 months) cycles of physiology and behavior that are crucial for life.

Xenohormesis Theory: ↑ Xenohormesis theory postulates that animals adapt to changes in environment by consuming substances produced by plants which act as signals of external conditions in which the plants were grown.

Polyphenols: ↑ Polyphenols are substances produced by stressed plants in response to the growing conditions. They are present in fruits and vegetables and can lead several health effects when they are consumed.

Chrononutrition: ↑ Chrononutrition is a new area of study that focuses on the interactions between biological rhythms, nutrition, and metabolism, as well as the implications for health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Original Source Article

↑Arola-Arnal, A., Cruz-Carrión, Á., Torres-Fuentes, C., Ávila-Román, J., Aragonès, G., Mulero, M., et al. 2019. Chrononutrition and polyphenols: roles and diseases. Nutrients 11:2602. doi: 10.3390/nu11112602

References

[1] ↑ Gerhart-Hines, Z., and Lazar, M. A. 2015. Circadian metabolism in the light of evolution. Endocr. Rev. 36:289–304. doi: 10.1210/er.2015-1007

[2] ↑ Howitz, K. T., and Sinclair, D. A. 2008. Xenohormesis: sensing the chemical cues of other species. Cell 133:387–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.019

[3] ↑ Dai, J., and Mumper, R. J. 2010. Plant phenolics: extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 15:7313–52. doi: 10.3390/molecules15107313

[4] ↑ Arola-Arnal, A., Cruz-Carrión, Á., Torres-Fuentes, C., Ávila-Román, J., Aragonès, G., Mulero, M., et al. 2019. Chrononutrition and polyphenols: roles and diseases. Nutrients 11:2602. doi: 10.3390/nu11112602