Abstract

The bacteria Salmonella is a major cause of food poisoning. Poultry products are one of the leading foods that cause Salmonella outbreaks. While farmers, food processors, and the public health community already do a lot to prevent these illnesses, people are still getting sick. Our group is studying how we can use the “good” bacteria in the intestines of chickens to drive Salmonella out of chickens. To test this idea, we used various diets to change the bacterial populations in chicken intestines. We found that changes in the numbers of good bacteria can lead to lower levels of Salmonella. We are currently working to identify which bacteria are responsible for the changes in the amount of Salmonella in the chicken intestines, with the goal of making a diet that will eliminate Salmonella from chickens. Hopefully, this will reduce the number of people who get sick from eating poultry products.

Salmonella Bacteria Cause Food-Borne Illness

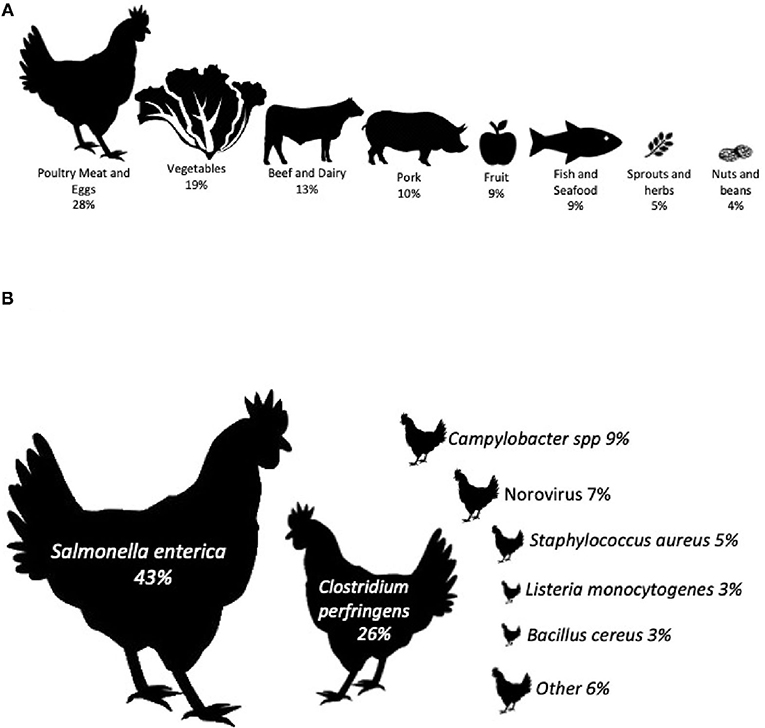

Have you ever eaten something and a few days later gotten really sick? You likely had what is commonly called food poisoning, also known as a food-borne illness. These illnesses are caused by bacteria or viruses that can infect you if the food you eat is not cooked properly. Different types of food can carry different types of bacteria or viruses, but chicken, eggs, and other poultry products are commonly associated with food-borne illness (Figure 1A) [1].

- Figure 1 - What types of food cause the most food-borne illness?

- (A) In the U.S., there were 5,760 outbreaks of food-borne illness from 2009 to 2015. Of those, 1,281 could be associated with a single food source. Poultry products (meat and eggs) caused the most illnesses, followed by vegetables, beef and dairy products, pork products, fruit, fish and seafood, sprouts and herbs, and finally nuts and beans [1]. (B) In 149 food-borne disease outbreaks in which people got sick from eating poultry products, almost half of them (43%) were caused by Salmonella [2].

Many kinds of bacteria and viruses can be associated with poultry products but, in the U.S., the bacteria Salmonella accounts for the largest number of food-borne illnesses from eating poultry products (Figure 1B) [2]. If you eat a chicken sandwich that is contaminated with Salmonella, 48–72 h later you could develop an infection, with symptoms including nausea, abdominal cramps, fever, chills, headache, vomiting, and diarrhea. This infection can last up to 7 days. Sometimes the infection can be so severe that you may have to go to the hospital1.

But how did Salmonella get into your chicken sandwich in the first place? Salmonella bacteria live in the environment. Chickens can pick up Salmonella when they peck at the food on the ground. All chickens, including those sold as organic, free-range, or natural, can pick up the bacteria. While Salmonella can make us sick, these bacteria do not make chickens sick. That means Salmonella can live inside the intestines (gut) of a chicken without us knowing. From there, Salmonella can find its way into the chicken’s eggs. Bacteria can also spread from the gut to the meat when a chicken is cut up. If the eggs and meat are stored and cooked properly, any Salmonella that may be present will be killed, so it will not make us sick. However, sometimes people do not cook their chicken well enough, or they accidentally spread Salmonella from raw chicken to other food2.

Can We Fight Salmonella in Chickens?

Farmers and food producers spend a lot of money trying to keep Salmonella out of food [3]. On the farm, chickens are often given vaccines to prevent Salmonella. However, there are over 2,600 different types of Salmonella. That is too many to make vaccines against all of them. At food processing plants, the eggs and meat go through many steps to wash away Salmonella before the food is packaged and sent to grocery stores and restaurants. Even with all of these efforts, poultry products still cause thousands of Salmonella illnesses each year [2]. To successfully keep Salmonella out of us, we need to figure out new ways of keeping Salmonella out of chickens.

One approach is to try to get other bacteria to help. Just like humans, chickens have trillions of “good” bacteria that live inside their guts. These good bacteria help chickens digest their food and they also produce nutrients that the chickens cannot make for themselves. These bacterial populations change in response to what the chickens eat. The various types of bacteria in the gut fight over food and resources to survive. We asked whether we could make chicken safer to eat by helping the good bacteria in chickens’ guts fight off Salmonella [4].

To test this hypothesis, we used three groups of 100 chickens each. We gave normal chicken feed to one group. This was our control group, and it was used to show us what the population of bacteria in the chicken gut normally looks like. We fed the second group chicken feed mixed with a type of fiber that only certain good bacteria can use as food. This bacteria food is known as a prebiotic. The types of bacteria that can eat the prebiotic make chemicals that should drive out Salmonella. We thought that increasing the numbers of these good bacteria might make the gut a place where Salmonella do not want to live. Our third group received normal chicken feed, but at the start of the experiment we gave them a Salmonella type that had been modified so it cannot make people sick. This was to test the possibility that adding a “safe” Salmonella to the chickens’ guts might prevent other Salmonella types from being able to live there. This is the bacterial equivalent of what you might do when you do not want someone to sit next to you at school: you get other people to sit around you first.

We let each group of chickens eat their assigned foods from the day they hatched until they were 35 days old. This gave the good bacteria plenty of time to grow. By day 35, there could be thousands of different types of bacteria in the chickens’ guts.

Diet Changes Bacteria in Chicken Intestines

Our hypothesis was that the prebiotic treatment and the safe-Salmonella treatment would change the populations of good bacteria in the chicken gut. We needed a way to measure how the gut bacteria in these chickens might be different from the bacteria in the guts of our control group. So how could we measure all the bacteria in the guts of these chickens? It would take a very long time and cost a lot of money to grow all these bacteria in the lab and count them by hand; not to mention that most of the bacteria that live in the gut cannot be grown in the lab. So, we performed a bacterial version of a crime scene investigation—we determined which bacteria were present based on the bacterial DNA we found in the gut. To do this, we collected samples of the partially digested food from inside the chickens’ guts, and we isolated the bacterial DNA from those gut samples.

To identify which bacteria were present in each gut sample, we tested for a specific bacterial gene known as 16S ribosomal RNA. Testing for this gene could tell us which types of bacteria were in each gut sample and how many of each type were there [4]. For each chicken, we then made a list of all the bacteria we found and the percentages of the bacterial population each type made up. We used a computer program that looked at all the bacteria we found in all chickens, and we grouped the chickens together based on the similarity of the bacterial populations in their guts. This analysis showed us whether there were differences among our groups of chickens.

Good Bacteria Can Reduce Salmonella in Chickens

If our prebiotic treatment or our safe-Salmonella treatment affects which bacteria can live in the gut, then we would expect the numbers and types of bacteria to be different between our experimental groups. This is essentially what we found! At the start of the experiment, there were no differences between the groups. The gut bacteria found in the chickens from all three groups were the same. However, 4 weeks after the start of the experiment, there were three distinct groups of bacterial populations: one for the control group, one for the prebiotic group, and one for the safe-Salmonella group.

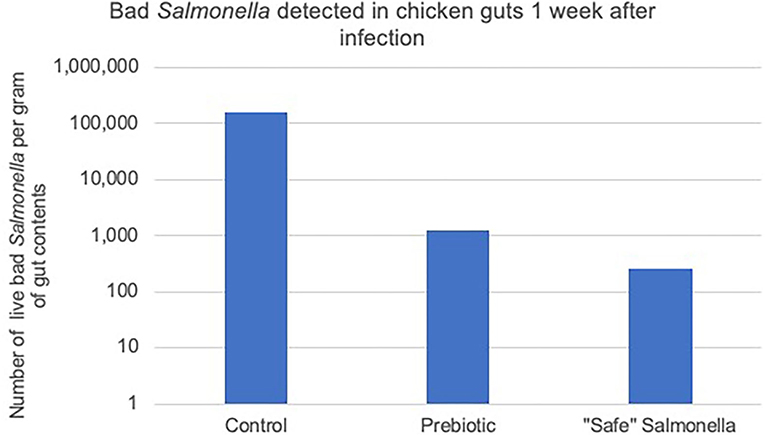

Once we knew that our diet treatments could change the bacterial populations in the gut, we wanted to see if the altered bacterial populations could prevent disease-causing Salmonella from living in the gut. Four-week-old chickens from each group were given disease-causing Salmonella. One week later, we collected gut samples from the chickens, like before. This time, we grew the bacteria in the lab, so we could count how many disease-causing Salmonella were in each chicken and compare those numbers among the three groups. In the control group, we found that chickens had an average of 100,000 disease-causing Salmonella bacteria per gram of gut material. However, chickens that had either the prebiotic treatment or the safe-Salmonella treatment had much lower levels of disease-causing Salmonella in their guts (Figure 2).

- Figure 2 - Changing the “good” bacteria in the chicken gut helps get rid of disease-causing Salmonella.

- After 4 weeks on either the control diet, the prebiotic diet, or the safe-Salmonella diet, we gave the chickens a dose of disease-causing Salmonella. One week later, we collected gut samples and measured how much disease-causing Salmonella was in the guts of seven chickens from each of our three groups. The safe-Salmonella group and the prebiotic group had less disease-causing Salmonella than the control group.

Keeping Humans Healthy

From these experiments, we learned that feeding chickens a prebiotic or giving them a safe Salmonella changes the kinds and amounts of bacteria living in chickens’ guts. We also learned that these changes can lead to lower levels of disease-causing Salmonella. Now we are trying to find out exactly which bacteria in the chicken guts are responsible for decreasing the growth of disease-causing Salmonella. We hope that by identifying the specific bacteria that prevent disease-causing Salmonella from living in chickens, and understanding exactly how these good bacteria manage to stop the Salmonella, we will be able to develop diets for chickens that will completely eliminate Salmonella from their guts. Since Salmonella-contaminated eggs and poultry products are a major source of Salmonella outbreaks in humans, eliminating Salmonella in the guts of chickens could greatly reduce the number of people who get sick from food-borne illnesses in the future.

Glossary

Food-Borne Illness: ↑ Sickness caused by eating or drinking something containing harmful bacteria, parasites, viruses, or chemicals. Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, and chills.

Control: ↑ A group of animals that does not receive any experimental treatment and is used to represent what normally happens and is compared to the other groups of animals to help the researchers determine how the effect the treatment.

Prebiotic: ↑ Nutrients used as food by gut bacteria. Prebiotics are used to encourage the growth of “good” bacteria in the gut.

DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid): ↑ Material found in cells that contain all the instructions a living thing needs to work and function.

Gene: ↑ Specific regions of DNA that contain the instructions for individual components of a living thing.

16S Ribosomal RNA: ↑ A gene (segment of DNA) found in bacteria that can be used to identify the types of bacteria in a population.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ↑Food poisoning - Causes, symptoms & treatment | Dr. Claudia” YouTube, Babylon Health, Jan 16, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JR6yHykfYJE.

2. ↑“How salmonella spreads from farm to table” YouTube, The Oregonian, Mar 26, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=duSDTYFNTi8.

Original Source Article

↑Azcarate-Peril, M. A., Butz, N., Cadenas, M., Koci, M., Ballou, A., Mendoza, M., et al. 2018. A Salmonella-attenuated strain and galacto-oligosaccharides accelerate clearance of Salmonella infections in poultry through modifications to the gut microbiome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84:e02526-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02526-17

References

[1] ↑ Dewey-Mattia, D., Manikonda, K., Hall, A. J., Wise, M. E., and Crowe, S. J. 2018. Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks — United States, 2009–2015. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 67:1–11. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6710a1

[2] ↑ Chai, S. J., Cole, D., Nisler, A., and Hahon, B. E. 2017. Poultry: the most common food in outbreaks with known pathogens, United States, 1998–2012. Epidemiol. Infect. 45:316–25. doi: 10.1017/S0950268816002375

[3] ↑ Dar, M. A., Ahmad, S. M., Bhat, S. A., Ahmed, R., Urwat, U., Mumtaz, P. T., et al. Salmonella typhimurium in poultry: a review. World's Poultry Sci J. 73:345–54. doi: 10.1017/S0043933917000204

[4] ↑ Azcarate-Peril, M. A., Butz, N., Cadenas, M., Koci, M., Ballou, A., Mendoza, M., et al. 2018. A Salmonella-attenuated strain and galacto-oligosaccharides accelerate clearance of Salmonella infections in poultry through modifications to the gut microbiome. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84:e02526-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02526-17