Abstract

For the first 3 years of life, the brain is hard at work trying to figure out how to speak and understand the language we hear. But for 1 in 12 children, this process does not work out so well and they develop a speech-language disorder. This means these children may have problems pronouncing words or problems making proper sentences. For example, they might say “sit on chair” instead of “sit on the chair,” or say “I wuve you” instead of “I love you.” These children then need to go to a therapist to practice saying the words properly or to learn how to make proper sentences. You probably have at least one friend who has problems with speaking. What has happened to that person? What is his or her life like? In this article, we want to talk about the process of speech therapy, when it is needed, and how it helps.

What Is a Speech-Language Disorder?

In the U.S., 1 out of every 12 children has a form of speech-language disorder [1]. That means that if you have a group of 12 friends, one of them will have problems with pronouncing words or putting sentences together. These problems do not need to be so extreme that they cannot talk at all. One of the most common problems is switching letters around or not saying the last letter of a word. For example, they might say “spacema” instead of “spaceman.”

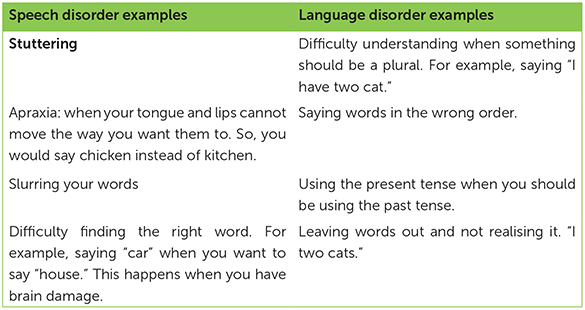

There are two types of speech-language disorders: speech disorders and language disorders. Speech is how we say sounds and words; language is how we use words to share ideas and communicate. If someone has a speech disorder, it means that that person cannot pronounce letters properly, or they switch letters around. These children might say “wed” instead of “red.” If someone has a language disorder, it means that that person has problems with putting sentences together. These people might also have problems understanding things like plurals. So, when they have multiple cats, they would not say, “I have two cats,” they will say, “I have two cat,” forgetting to put the “s” at the end of cat to make it a plural. So, a speech disorder refers to the sounds of words and letters, whereas a language disorder refers to the meaning and grammar of sentences. We have put some examples in

Now, be careful when trying to figure out if you know anyone with a speech-language disorder. Sometimes words sound different not because someone has a disorder but because that person has an accent. For instance, I always pronounce Tuesday as tch-u-sday, whereas my sister pronounces it as too-sday. Neither of us has a speech-language disorder; we just have different accents.

Speech-language disorders can occur in a variety of different ways. Sometimes, people’s brains have problems figuring out how to make their mouths and tongues move in the proper way to make the sounds they want to make. So, they know they have to say “red,” but no matter how hard they try, it always comes out as “wed” instead. Sometimes, this is because people have problems learning. On average, by the time we are 3 years old, we can make very basic sentences to talk to our parents and the people around us. But, for some children, this process takes longer. These children might have problems learning other things as well, like reading. And sometimes children have speech-language disorders as a side-effect of a bigger problem. For example, they might have cerebral palsy, which means that the muscles in their bodies do not work as well as they should. You need a lot of muscles to pronounce words properly, so if your muscles do not work very well, then it is harder to make your mouth create the right sounds. Or, children might be deaf, and unable to hear that they are making the wrong sounds, so that they cannot correct themselves. There are many different reasons why people might have speech-language disorders.

Currently, we do not really know what happens in the brain that causes some children to have speech-language disorders. Sometimes only the language parts of the brain are not working properly, but at other times many different parts of the brain might be malfunctioning, such as the area responsible for remembering sounds or the area responsible for paying attention. Because multiple regions of the brain can be involved, sometimes speech-language disorders come along with other problems, like autism spectrum disorder. A lot of research is still being done to figure out what is happening in the brain during speech-language disorders, because this research will help to make treatments more effective.

What Happens if You Have a Speech-Language Disorder?

I think the best way to explain what happens if you have a speech-language disorder is to tell you a story. The story is about a boy, let us call him Mark. Mark has an older sister, who learned to talk like most babies learn to talk. So, by the time Mark was 18 months old, his parents became worried that Mark was not speaking like his sister did when she was his age. Mark’s parents took him for an assessment, which is a small test conducted by a speech language pathologist, a person who is trained to figure out if someone has a speech-language disorder and to come up with a plan for how to fix it. Because Mark was still a baby, he was invited to just play with the pathologist. By playing certain games, the pathologist got Mark to describe things, or to follow instructions. This way, the pathologist could see whether Mark indeed had problems, and what those problems might be. If Mark had been a bit older, the pathologist probably would have given him a more structured test, in which Mark would have been shown pictures and asked to name what was in the pictures.

The speech-language pathologist made a list of all the things Mark had problems with, with the most important at the top. This way, when Mark goes into speech-language therapy, the therapist will work on the most important things first, and slowly work her way down the list. Sometimes the things at the bottom of the list fix themselves, just by going to therapy! Children like Mark usually only go to therapy once a week. The rest of the time, they go to school, go to clubs, and hang out with friends. It is very likely that you might know a kid like Mark.

What Happens During Therapy?

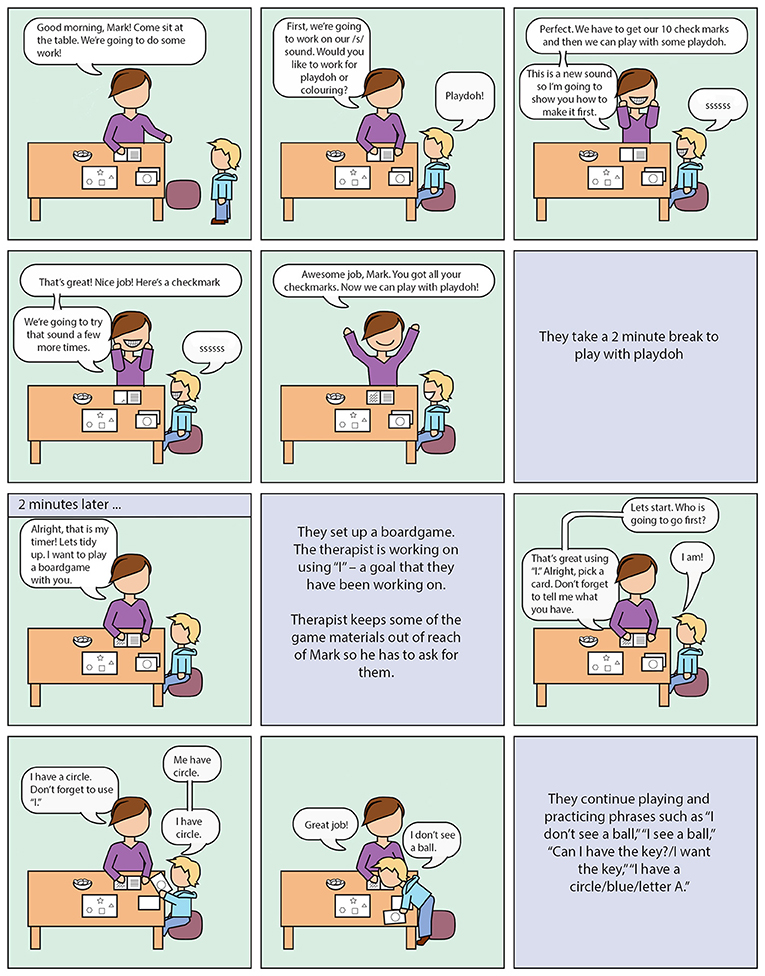

One thing that Mark does during therapy is play games. A favorite of his is called Cariboo, a game where he has to describe cards and open doors on the gameboard that match something on the card. This way, Mark must speak out loud, and the therapist can correct him if he says something wrong. The game only contains pictures, so it does not matter if Mark cannot read yet. Cariboo can also help the therapist to see if Mark has problems understanding what is on the card. For example, if he has a red card but opens a door with green apples on it, he might have problems matching things. Sometimes, Mark plays with other toys together with his therapist. For example, they might race cars and say things like “crash” when the cars hit each other or blow bubbles and say “pop” when they pop. It is important that these things are fun for Mark, so he does not really feel like he is having therapy—he is just having fun. For all kids receiving speech-language therapy, having fun with their therapists is very important. Usually, these kids are shy and do not want to talk, because they know they are not doing it correctly. By making Mark feel comfortable, the therapist became his friend and eventually Mark was more willing to communicate with her.

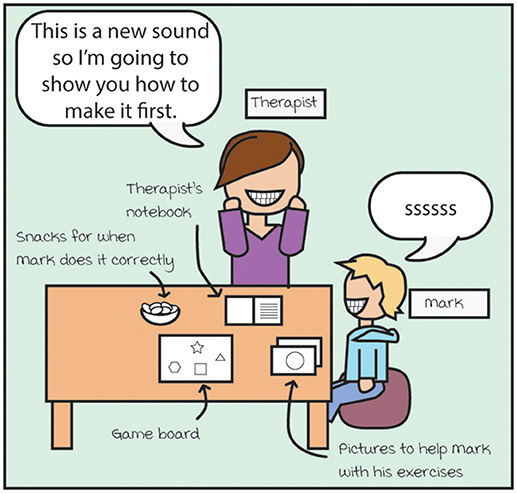

During therapy, there are both structured and unstructured activities. The activities that are more structured (more controlled) include times when the therapist and Mark sit at a table and work on a specific sound together (Figure 1). The unstructured (less controlled) activities seem more as if they are just playing together (see Figure 2). The therapy can occur at the child’s house, but it can also occur at a therapy center.

- Figure 1 - Mark and his therapist.

- This is an example of a structured, or controlled, activity. The therapist and Mark are practicing the “s” sound together. On the table is the therapist’s notebook, so she can take notes on how well Mark is doing. The therapist might also show Mark pictures that he has to describe, for example something with the “s” sound, like “circle.”

- Figure 2 - An example of a therapy session.

- Here is an example of a typical therapy session, so you can see the types of activities that children do with their therapists.

Who is the therapist that Mark goes to? A speech-language therapist is someone who has learned a lot about language and how it can go wrong. To become a speech-language therapist, first you have to go to university, to learn about language and the brain, and then go to another school, called a graduate school, to learn about what happens when speech and language go wrong, and how you can help someone with these problems.

Conclusions

You might know someone in your class with a speech-language disorder. Unlike most problems with the body, it is usually not that important how the speech-language problems started. Speech-language disorders can occur for a variety of different reasons, some of which we listed in this article. But the therapy is usually the same for everyone: practice, practice, practice. Therapy involves either playing games, or having a more class-like setting, with activities like naming pictures. And do not worry, the therapy does not last forever. The average length of time a child has therapy is usually a year, but it can be longer or shorter, depending on how fast the child learns.

Do you think you might have a speech-language disorder? If you parents were worried, they would probably have taken you for an assessment by now. If you feel like you might have a small problem, like a lisp, do not worry. Most of these small speech problems fix themselves without therapy, before you become a teenager.

Glossary

Disorder: ↑ Something that is wrong. Dis-order stands for out-of-order, so something is not as it should be.

Stutter: ↑ A speech disorder in which people accidentally repeat certain letters in a word. So, they may say “z-z-z-z-zebra” when trying to say “zebra.”

Malfunction: ↑ The meaning is very similar to disorder. Mal-function is something that is not functioning, or working, the way it should.

Speech-Language Pathologist: ↑ A pathologist is a specialist who is able to identify which disease a patient has, very much like a doctor. A speech-language pathologist is therefore someone who can identify what is wrong with the speech and/or language of a person.

Lisp: ↑ A speech disorder in which people pronounce “s” as “th.” So, instead of saying “sick,” they will say “thick.” This is also true if they try to pronounce “z.” So, they will say “thebra” instead of “zebra.”

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Black, L. I., Vahratian, A., and Hoffman, H. J. 2015. Communication Disorders and Use of Intervention Services Among Children Aged 3–17 years: United States, 2012. NCHS data brief, no 205. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.