Abstract

People with an intellectual disability have lower intelligence than others and find it hard to do things necessary for day-to-day living, like communicating or taking care of themselves. There are different levels of intellectual disability, from mild to severe and profound. People with an intellectual disability often have many health problems, but it is often difficult for them to get good healthcare. They find it difficult to understand the complex language that many doctors and other health professionals use. Most health professionals have never learned how to treat people with an intellectual disability and they are not confident when they treat a person with an intellectual disability. Disability services and health services should work together as a team. Better healthcare for people with an intellectual disability is important, so that fewer people die because they did not get the healthcare they needed.

What Is an Intellectual Disability?

We all have things that we are good at and things that we might need help with. This is the same for people with an intellectual disability. People with an intellectual disability have lower intelligence, they learn more slowly than other people their age and have delays in their development. They can have problems with:

- Thinking

- Remembering things

- Talking and listening

- Moving around (e.g., walking and running)

- Controlling their feelings

- Looking after themselves (e.g., washing, dressing, and feeding themselves).

For people with an intellectual disability, these problems begin to occur in childhood, or before they turn 18 years old. Because of these problems, people with an intellectual disability might need extra help at school, at work, and at home. The amount of help they need depends on the level of the intellectual disability.

Sometimes, an intellectual disability can be an invisible condition. For people with mild intellectual disabilities, other people may not notice the intellectual disability immediately. Even those people whose intellectual disabilities are not noticeable still face challenges in their everyday activities and may need extra support.

What Are the Levels of Intellectual Disability?

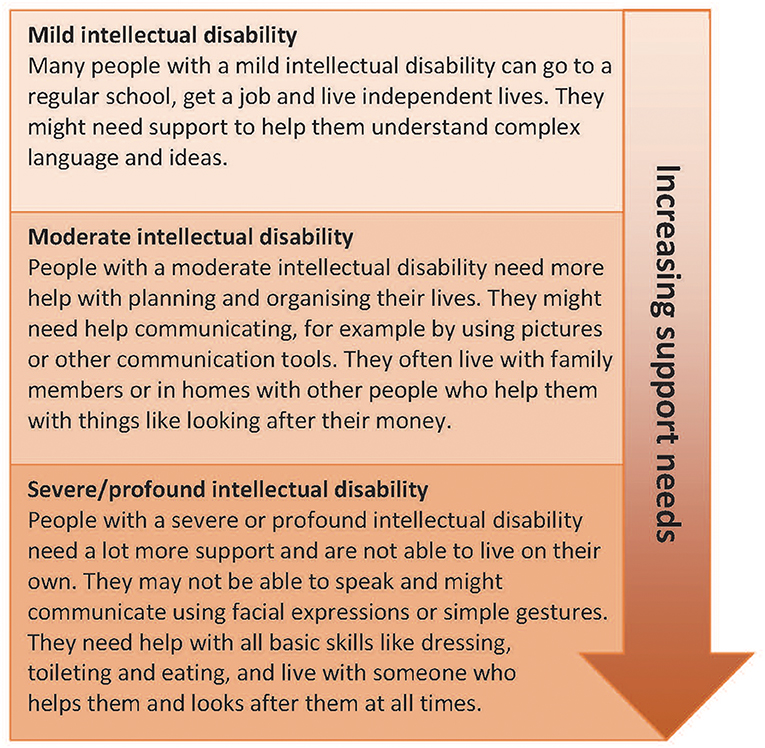

There are different levels of intellectual disability: mild, moderate, severe, and profound (see Figure 1). You may know someone with Down syndrome, which is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability. Usually, people with Down syndrome have mild or moderate intellectual disability. Around 85% of people with an intellectual disability have a mild form. Many people with mild intellectual disabilities can go to regular schools, get jobs, and live independent lives. People with moderate intellectual disabilities need more help with planning and organizing their lives. They might need help communicating, by using pictures or other communication tools. They often live with family members or in homes with other people who help them with things like looking after their money. People with severe or profound intellectual disabilities need a lot more support and are not able to live on their own. They may not be able to speak and might communicate using facial expressions or simple gestures. They need help with all basic skills, like dressing, toileting, and eating, and they live with people who help them and look after them at all times.

- Figure 1 - Levels of intellectual disability and support needs at the different levels.

What Causes an Intellectual Disability?

There are several things that can cause a person to have an intellectual disability. These can include genetic conditions like Down syndrome, problems during pregnancy or birth, an injury to the brain, or an infection or illness. Sometimes the cause of a person's intellectual disability might not be known.

Health Problems in People With an Intellectual Disability

Most people with intellectual disabilities have a lot of problems with their health (see Figure 2). These can be physical health problems, such as:

- Heart problems

- Obesity

- Epilepsy

- Dental problems

- Vision and hearing problems

- Injuries (e.g., fractures)

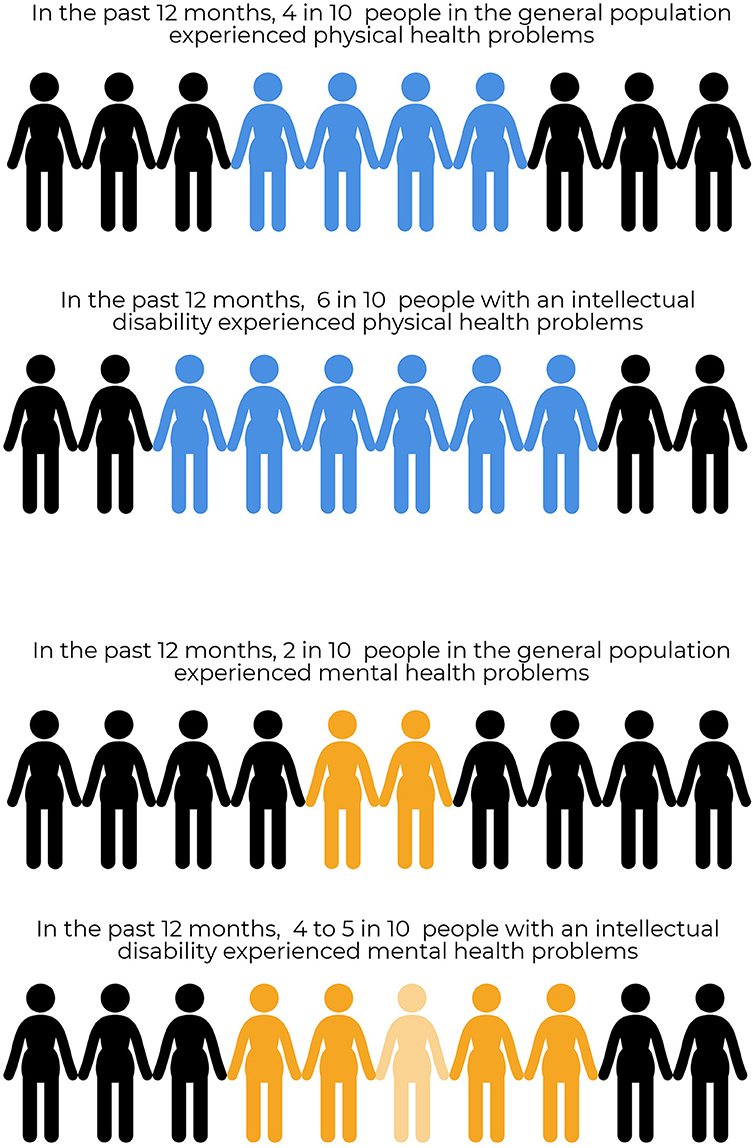

- Figure 2 - Many people with an intellectual disability have more physical and/or mental health problems than does the general population.

These people can also have mental health problems, such as:

- Depression (feeling sad, down, or miserable most of the time or not being interested in activities they used to enjoy)

- Anxiety (inability to stop worrying about things, thinking situations are much worse than they are, having intense fears about things or situations, or having repetitive unwanted thoughts)

- Psychosis (believing or sensing things that are not real, for example seeing or hearing something that is not there)

People with an intellectual disability have more physical health problems than do people without intellectual disabilities, and they also have double the rate of mental health problems [1, 2].

Many people with an intellectual disability have more than one physical or mental health problem and need help from different types of doctors and other health professionals. Because of the high rates of physical and mental health problems, people with an intellectual disability often die younger than do people without an intellectual disability. One of our research studies showed that, on average, people with an intellectual disability lived until they were about 54 years old, while people without an intellectual disability lived until they were about 81 years old [3]. Many people with an intellectual disability have died because they did not get the best healthcare.

Why Is It Harder for People With an Intellectual Disability to Get Good Healthcare?

It can be hard for people with an intellectual disability to find information about their health that they can understand. They can also find it hard to go to the doctor. Many doctors do not know how to speak to a person with an intellectual disability. Most doctors never learned how to treat people with an intellectual disability, so doctors are not confident when they treat a person with an intellectual disability [4, 5]. It can be difficult for a doctor to find out what kind of health problems a person with an intellectual disability has, especially if they cannot talk. Many doctors might think that a person is feeling or behaving in a certain way because they have an intellectual disability, instead of a physical or mental health problem. People with an intellectual disability often cannot tell a doctor what is wrong with them and they often have many health problems at the same time, which can be complicated to treat. Sometimes, health services say that they cannot help people with an intellectual disability, and that they need to go somewhere else for help. This is a big problem, because any person who gets sick should be able to get help easily.

What Do We Need to Do to So That People With an Intellectual Disability Can Get Good Healthcare?

People with an intellectual disability, their families and caregivers, and other people who support them (e.g., doctors), all agree that we need to improve access to healthcare and services for people with an intellectual disability. Our researchers spoke to people about what health professionals need to do so that people with an intellectual disability get good healthcare (see Figure 3).

- Figure 3 - What health professionals need to do to improve access to healthcare services.

The people interviewed said that it is important that health professionals learn how to communicate and how to treat people with an intellectual disability. Also, health professionals should make sure that a person with an intellectual disability understands the information that the doctor provides and is supported in making decisions about their health. Often, information about health issues is written in complicated language that people with an intellectual disability cannot understand. It would help if doctors and other health service providers would write information in simple language. Disability services and health services should work together as a team. Improving healthcare for people with an intellectual disability is important, so that fewer people die because they do not get the best healthcare. Further research into the healthcare needs of people with an intellectual disability is also important, to show which other aspects of the healthcare system need to be improved.

What Can Children and Young People Do to Support People With an Intellectual Disability?

People with an intellectual disability may not be able to communicate the same way as people without an intellectual disability, but they still feel the same full range of emotions. Just like everyone else, a child with an intellectual disability needs friends and they need to do the same things other children are doing at school and at home. You should treat people with an intellectual disability the same way you would treat any other friend, by being open and kind. Tell a teacher if you see teasing or bullying happening at school. When you talk to someone with an intellectual disability, use short and simple sentences, and give the person enough time to respond. They might speak more slowly or get stuck on some words. Let them express themselves at their own pace and be patient. If you are playing a game or doing an activity, be friendly and include them in whatever you are doing.

When more people speak up for the rights of people with an intellectual disability it will help to make intellectual disability more “visible.” This is an important step toward making sure that people with an intellectual disability are treated fairly and equally.

Where Can You Find More Information?

The Department of Developmental Disability Neuropsychiatry (3DN) at the University of New South Wales in Sydney does research to improve mental health policy and practice for people with an intellectual disability. This means we use the findings from our research projects to help government and health professionals to treat people with an intellectual disability in a better way. You can find more information about what we do and links to other organizations that help people with an intellectual disability on our homepage: https://3dn.unsw.edu.au/.

Glossary

Intellectual Disability: ↑ A neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by impairments in intellectual and adaptive functioning (for example, independent living) with onset during childhood.

Intelligence: ↑ The ability for problem-solving, planning, learning and understanding abstract concepts and to adapt to new situations.

Healthcare: ↑ Provision of medical care by providers such as general practitioners (GPs), medical specialists, allied health workers and nurses to maintain or improve physical and mental well-being.

Disability services: ↑ A range of support and services for individuals, families and carers, such as support to live independently, involvement in the community, assistance with employment and/or learning skills.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Cooper, S.-A., Smiley, E, Morrison, J., Williamson, A., and Allan, L. 2007. Mental ill-health in adults with intellectual disabilities: prevalence and associated factors. Br. J. Psychiatry 190:27–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022483

[2] ↑ Cooper, S. A., McLean, G., Guthrie, B., McConnachie, A., Mercer, S., Sullivan, F., et al. 2015. Multiple physical and mental health comorbidity in adults with intellectual disabilities: population-based cross-sectional analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 16:110. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0329-3

[3] ↑ Trollor, J., Srasuebkul, P., Xu, H., and Howlett, S. 2017. Cause of death and potentially avoidable deaths in Australian adults with intellectual disability using retrospective linked data. BMJ Open 7:e013489. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013489

[4] ↑ Lennox, N. G., Brolan, C. E., Dean, J., Ware, R. S., Boyle, F. M., Taylor Gomez, M., et al. 2013. General practitioners' views on perceived and actual gains, benefits and barriers associated with the implementation of an Australian health assessment for people with intellectual disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 57:913–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01586.x

[5] ↑ Weise, J., and Trollor, J. N. 2018. Preparedness and training needs of an Australian public mental health workforce in intellectual disability mental health. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 43:431–40. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2017.1310825