Abstract

The human body is composed of many systems and organs that work together to ensure our well-being and survival. Hormones are the messengers that allow the organs to communicate. The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland located in the neck that uses iodine from the diet (mainly present in seafood) to produce thyroid hormones: thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). The thyroid hormones are very important for brain development, growth, and metabolism. A lack of iodine impairs the production of thyroid hormones, which can lead to mental disabilities. An excess of thyroid hormones is not good for us either, and may compromise many of the body’s functions. So, when it comes to hormones, “balance” is the keyword. In this article, you will learn the importance of thyroid hormones for human health.

Iodine is an essential element that we get from the foods we eat. The lack of iodine can seriously affect human health, causing many medical problems including mental disabilities in children [1]. Since 1920, to minimize the problems related to not ingesting (taking in) enough iodine, many countries have been adding iodine to table salt [2]. But how can a single element affect us so much?

The human body does not produce its own iodine; therefore, we get it from our diets. Seafood is the biggest dietary source of iodine, and people who live close to the sea get plenty of this element. Seafood is readily available in those areas and rain also transports iodine to the surrounding soil, where vegetables and fruits are cultivated.

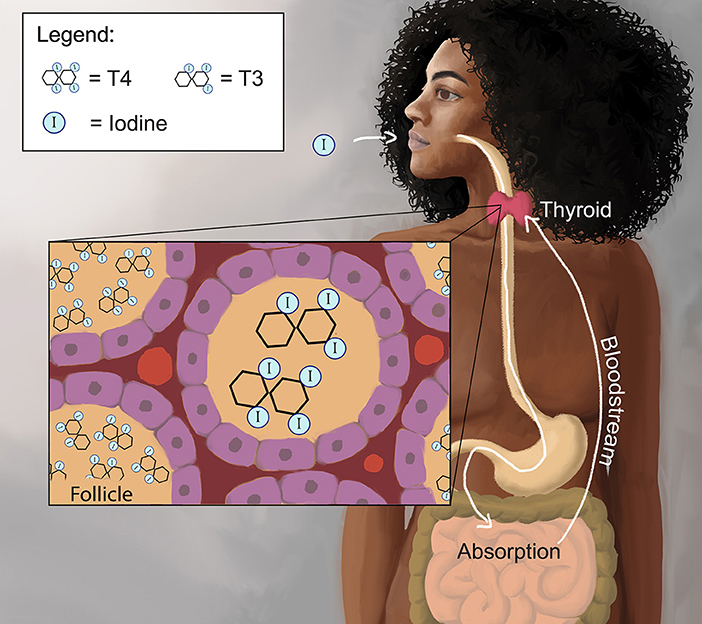

Once we ingest foods rich in iodine, the iodine is absorbed by our intestines and travels through the bloodstream to the thyroid gland, which is located in the neck (Figure 1). The name “thyroid” comes from the Greek words “thyreós,” meaning “shield,” and “ides,” meaning “shape.” So, the thyroid gland is shaped like a shield—or kind of like a butterfly! Which do you prefer?

- Figure 1 - Iodine (I) present in the foods we eat is absorbed in the small intestine and reaches the thyroid gland through the bloodstream.

- In the fluid inside the thyroid follicle, three or four iodine molecules are bound to a molecule called thyronine (represented by two hexagons) to form the thyroid hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and tetraiodothyronine (T4).

The Importance of Iodine to the Thyroid Gland

The function of the thyroid gland is to produce hormones. But what are hormones? Hormones are like text messages sent between the body’s organs. The messages sent by the hormones of the thyroid gland are delivered to all organs and cells in the body. Imagine that you and your friends are holding hands to form a circle—this is how the cells in the thyroid gland are organized, forming a circle named the thyroid follicle (Figure 1). The outside of the thyroid follicle is near blood vessels, while the inside contains a watery solution rich in iodine atoms and many proteins needed for thyroid hormone production.

In the thyroid gland, iodine can be stored until it is needed, or it can be used to produce two thyroid hormones: triiodothyronine (T3), which has three iodine molecules, and tetraiodothyronine (T4)1, which has four iodine molecules [3]. Thus, the difference between these two hormones is the number of iodine molecules attached to the main molecule, thyronine (Figure 1).

How Does the Body Control Thyroid Hormone Production?

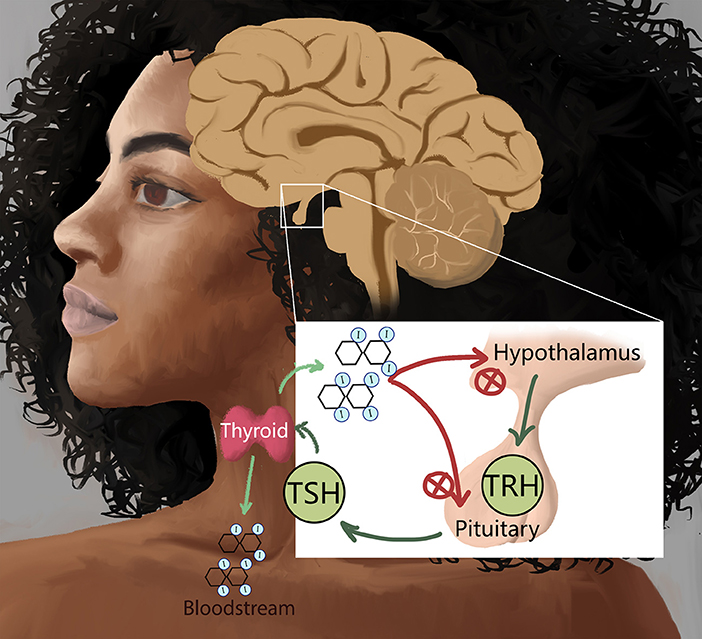

Organizing the function of thyroid cells is complex, and this job belongs to other hormones from two key areas of the brain: the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland. The hypothalamus produces thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), the commander-in-chief of the entire system. TRH signals to the pituitary gland, which is a powerful gland the size of a pea, to produce thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). TSH is the messenger sent by the pituitary to the thyroid, telling the thyroid to produce T3 and T4 [4] (Figure 2). If the body is functioning normally, there is a good balance of T3 and T4 going to all the organs. This balance is very important to maintain the body’s functions and to help the brain works properly. When the amounts of T3 and T4 in the bloodstream are high, this signals the hypothalamus and pituitary to produce less TRH and TSH, which slows down the production of T3 and T4 by the thyroid.

- Figure 2 - Two brain areas, the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland, interact with the thyroid gland to regulate the production of thyroid hormones T3 and T4.

- The hypothalamus releases TRH, which causes the pituitary to release TSH. TSH stimulates the thyroid gland to produce T3 and T4. The amounts of T3 and T4 in the bloodstream tell the hypothalamus and pituitary whether the thyroid needs to be more stimulated or less stimulated. This loop regulates the production and levels of T3 and T4.

When T3 and T4 levels drop enough, TRH and TSH do their part again, waking up the thyroid gland and telling it to produce more T3 and T4. It is like a loop!

What Message Do T3 and T4 Deliver?

Remember, the function of a hormone is to deliver a message to the organs and cells of the body. T3 and T4 are great messengers. The thyroid hormones regulate some of the body’s vital functions, such as controlling body temperature and, together with other hormones, adjusting the amount of energy available to fulfill the body’s energy needs. These processes are called basal metabolism, and the thyroid hormones do all this through the messages they deliver to the liver, heart, pituitary, kidneys, bones, brain, and many other organs.

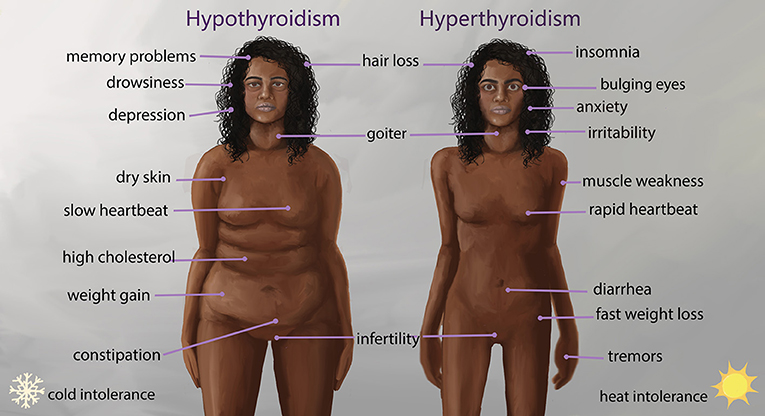

Before a baby is born and during childhood, thyroid hormones are extremely important for the growth and development of the brain and its functions. This is why babies and children who do not ingest enough iodine can develop mental disabilities. Without the right amount of iodine, the thyroid gland cannot produce its hormones properly and, under these conditions, babies, children, and even adults can develop a disease called hypothyroidism (Figure 3). “Hypo” means low; thus, hypothyroidism means low thyroid function. People with hypothyroidism feel cold, tired and depressed. Their thoughts, reflexes, and heart rates are slow. They may also have constipation and a tendency to gain weight because their basal metabolism is reduced.

- Figure 3 - Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism have symptoms that involve many organs and body systems.

- Hypothyroidism is usually associated with drowsiness, depression, memory problems, slow reflexes and heartbeats, constipation, cold intolerance, high cholesterol levels, and weight gain. Hyperthyroidism can lead to insomnia, anxiety, irritability, tremors, heat intolerance, rapid heartbeat, weight loss, and diarrhea. Both thyroid disorders can cause hair loss, goiter, and infertility.

On the other hand, when the thyroid produces too much thyroid hormone, hyperthyroidism can result. “Hyper” means higher. People with hyperthyroidism can be anxious, have tremors or insomnia, and can get angry very easily. They usually lose weight because of a high basal metabolism, and their heart rates are fast and strong, which can lead to heart palpitations and other heart problems. Both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism impair metabolism, reproduction, sleep, and memory.

Thyroid disorders are one of the most prevalent diseases across the world today. About 200 million people have hypothyroidism and many of them do not even know it! As you have learned, problems in the production of thyroid hormones can impair metabolism and affect the brain, kidneys, liver, intestines, and heart, as well as reproduction and growth [5, 6]. For the thyroid to do its job of making sure we get the right amounts of hormones, we must ingest the proper amount of iodine. The recommended daily allowances for iodine intake are 90 mcg/day for children, 120 mcg/day for teenagers, and 150 mcg/day for adults. Pregnant and breastfeeding women need 220–290 mcg/day. The need for iodine explains why many countries decided to add iodine to table salt [2]. However, ingestion of too much iodine (greater than 1,100 mcg/day) also damages the thyroid gland and may cause thyroid dysfunction. So, regulatory agencies must monitor iodine levels in manufactured table salts and in processed foods. We ourselves must also pay attention to the amount of iodine in our foods, so we do not exceed the body’s needs. Taking care of the thyroid gland is an important part of taking care of our health!

Glossary

Hormone: ↑ A substance produced by some cells to communicate with other cells and organs.

Triiodothyronine (T3): ↑ A hormone produced by the thyroid gland that contains three iodine molecules. T3 can be generated from the removal of one iodine molecule of T4.

Tetraiodothyronine (T4): ↑ A hormone produced by the thyroid gland that contains four iodine molecules.

Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH): ↑ A hormone produced by the hypothalamus that stimulates the pituitary to produce and release TSH.

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH): ↑ A hormone produced by the pituitary that tells the thyroid gland to produce and release T3 and T4.

Basal Metabolism: ↑ Set of chemical and enzymatic reactions that happen in the body being essential for survival.

Hypothyroidism: ↑ is a common disease in which the thyroid gland does not produce enough thyroid hormones.

Hyperthyroidism: ↑ A disease that results from the over activity of thyroid gland producing too much thyroid hormones.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (403972/2021-3) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (APQ-00013-22).

Footnote

1. ↑The nickname of T4 is thyroxine, and that is how most people know it.

References

[1] ↑ Organization, W. H. 2007. Assessment of Iodine Deficiency Disorders and Monitoring Their Elimination: A Guide for Programme Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43781.

[2] ↑ Health SoP. The Nutrition Source Available online at: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/iodine/.

[3] ↑ Berne, R. M., and Koeppen, B. M. 2010. “The thyroid gland,” in Berne & Levy Physiology, ed B. A. Koeppen Bms (Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier).

[4] ↑ Zoeller, R. T., Tan, S. W., and Tyl, R. W. 2007. General background on the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 37:11–53. doi: 10.1080/10408440601123446

[5] ↑ Bargi-Souza, P., Peliciari-Garcia, R. A., and Nunes, M. T. 2019. Disruption of the pituitary circadian clock induced by hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism: consequences on daily pituitary hormone expression profiles. Thyroid 29:502–12. doi: 10.1089/thy.2018.0578

[6] ↑ Peliciari-Garcia, R. A., Bargi-Souza, P., Young, M. E., and Nunes, M. T. 2018. Repercussions of hypo and hyperthyroidism on the heart circadian clock. Chronobiol. Int. 35:147–59. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2017.1388253