Abstract

School-aged athletes face the need to balance competitive sports and their studies. In doing so they follow what is called a dual-career pathway. Both pursuits take time and effort, both are expected to lead to success, and either could lead to a life-long career. A dual-career pathway begins when children start to play sports and might continue throughout the school years and beyond. Research shows that it is beneficial to combine sport and studies, but it is also challenging. How can kids optimally juggle their sport, studies, social, and private lives? How do they gain the benefits of a dual career and avoid harming their prospects in sport or school? This article explains what a dual career is, why it is important, and why it is difficult. It also describes the skills and strategies for coping with dual-career challenges and presents tips from researchers to achieve success in dual-career pursuits.

What Is a Dual Career?

Many young readers are engaged in sport training and competitions while simultaneously pursuing an education. In the field of sport sciences, such a combination is called a dual career. A dual career requires managing two major activities, both of which are important. Young people are in school during the same years that are favorable for developing talent in sport. So, young athletes find themselves on a dual-career path. Researchers in the field of talent development estimate that it takes 10,000 h of purposeful practice to reach an expert level in sports, music, or performing arts [1]. Therefore, an athletic career often begins during childhood and continues through youth and adulthood as the young person progresses through primary school, secondary school, high school, and college/university education. Such an athletic career flows through the following stages:

- Initiation—an introduction to sports and playing for fun,

- Development—an emphasis on one sport, learning sport-specific skills, and involvement in structured practice and competitions,

- Mastery—achieving a personal peak in sport performance and possibility of pursuing sport professionally,

- Discontinuation—leaving competitive sports and shifting priorities to education or work.

Why Is a Dual Career Important?

Sport psychology researchers view athletes as whole individuals, who not only engage in sport, but also have other life priorities such as education, work, family, friends, and hobbies. Human life is viewed as a personal journey through various “landscapes,” which include physical places, historical periods, and developmental stages (childhood, youth, adulthood, and older ages). We rarely journey alone in life. Parents, siblings, teachers, coaches, teammates, and peers might place expectations and demands on us, and also provide us with support and care. For example, in one study researchers interviewed athletes from all over the world about their dual-career experiences [2]. All the athletes interviewed acknowledged the importance of their support networks. Supporters in the athletes’ lives had a strong belief in the value of education and a whole-person approach, they understood what athletes go through, and they helped the athletes to face barriers along the way. An athlete’s support network and the help those people supplied were viewed as key factors for dual-career success.

In life’s journey, it is important to do things at the right time, which requires good planning and preparation for the future. Athletes with dual careers aim to win in the short and long run. Winning in the long run means preparing for adult life by getting an education, which provides future job and financial security. Researchers interviewed 15 former Olympic athletes and revealed that dual-career athletes adjusted better and experienced less difficulty finding their places in society after exiting sport than did those athletes who put sport ahead of everything else [3]. So, by having multiple pursuits, student-athletes create a safety net for the future. Winning in the short run means reaping more immediate benefits of combining sport and studies. One of these benefits, revealed by another group of researchers, is that changing from a mainly mental activity (studies) to a mainly physical one (sport) is a form of recovery from the other activity [4]. These athletes also built resilience by thinking “It is great to do well in both sport and school, but if I fail in one, I have the other to fall back on.”

Why Is a Dual Career Difficult?

In both sport and studies, young people have goals or visions of what they want or ought to achieve. Some goals are set by the young people themselves and may include making a national team or “acing” a school test. Other goals might be communicated to young people by coaches, teachers, family members, or peers, and then accepted by young people. The difficulty of each new goal is determined by the person’s resourcefulness, which means the degree and quality of resources this person has to reach the goal in mind. Resources are internal (such as a person’s character, skills, and experience) and external (such as the availability of support) factors or assets facilitating goal achievement. Depending on their resourcefulness, a young person might see a goal as routine (readily achievable), challenging (difficult, but achievable with additional resources), or risky (too far from readily achievable). The same demand or goal can present a different level of difficulty from person to person, depending on how resourceful the person is.

Sport and studies each present their own challenges but combining them into a dual career adds a whole new layer of challenge. For example, doing important things on time, allowing time for physical and mental recovery, and still finding time to nourish friendships and participate in family events can be especially challenging. One group of researchers created a questionnaire to study student-athletes’ challenges and their dual-career competencies [5]. These competencies included using time efficiently, prioritizing tasks, setting realistic goals, viewing setbacks as growth opportunities, seeking advice from the right people at the right times, listening and learning from others and from past experiences, and being flexible to alter plans if necessary. Responses from 3,247 student-athletes representing nine European countries revealed that the participants found all the competencies important, and possession of such competencies contributed significantly to their success in coping with dual-career challenges.

What Are The Secrets of Dual-Career Success?

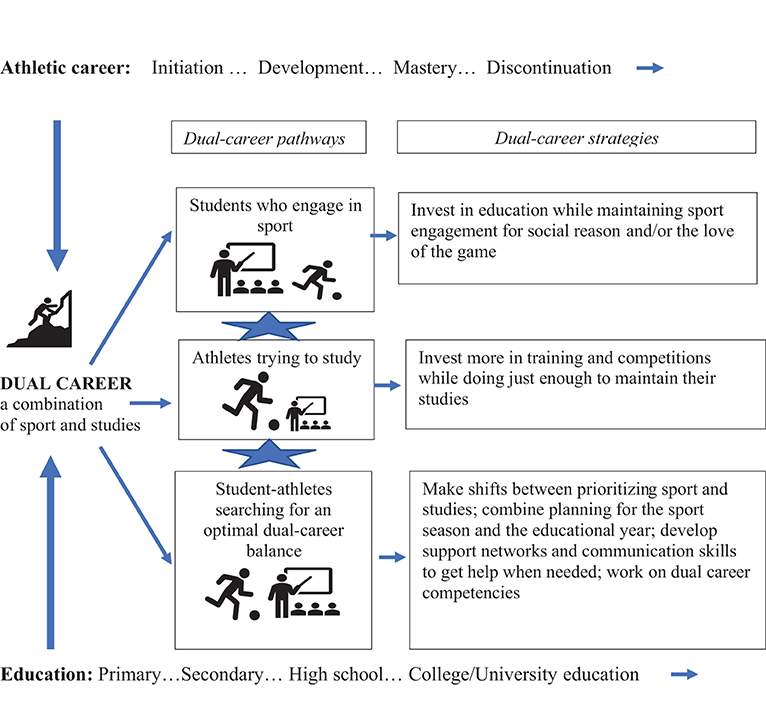

In one interesting study, researchers surveyed and interviewed athletes at the beginning and the end of the first educational year at a national elite sport school [4]. The athletes confessed to experiencing challenges and noted that it was impossible to constantly invest 100% into both sport and education. The research showed how the sport-education balance was individual and changing. Depending on how they perceived the relative importance of sport and academics, student-athletes could be divided into—and freely shift between—three categories: students who engage in sport, athletes trying to study, and student-athletes searching for an optimal dual-career balance (Figure 1).

- Figure 1 - Dual-career pathways and strategies.

- Athletes fall into, and can freely switch between, three different dual-career pathways, depending on how they view the relative importance of sport and studies at a given time. Each pathway is characterized by specific strategies for balancing sport and studies.

Student-athletes in the first category dream of high achievement in sport, but over time often find these dreams unrealistic and invest more of themselves in education. In their dual-career pathway, they maintain sport engagement for social reasons or for the love of the game. The second category of student-athletes sees sport as their passion and education as a need, so in their pathway, they focus more on sport training and competitions, while doing just enough to maintain their studies. The third category of student-athletes tries to find an optimal dual-career balance. Dual-career balance is defined as a combination of sport and studies that allows student-athletes to reach their sport and study goals, lead a satisfactory social and private life, and stay healthy both mentally and physically. In offering some useful strategies to find such balance, researchers [4] recommended that young people:

- Make shifts between prioritizing sport and studies. Give more time and effort to the prioritized role and any relevant tasks, while simply maintaining the other role and relevant tasks;

- Combine planning for the competitive sport season and the academic year;

- Develop support networks (family, sport and study peers, coaches, teachers, and counselors) and communication skills to get help when needed; and

- Work on dual-career competencies.

How Can You Work on Your Dual-Career Competencies?

There are basic competencies that are transferable or movable from one activity or sphere of life (where they were initially developed) to another, making these competencies even stronger. To conclude this article, here are some recommendations, based on our many years of research in this field, for becoming more resourceful when dealing with dual-career challenges:

- Set realistic goals. Goals should be challenging but achievable. Avoid risky goals that might compromise your mental health and wellbeing. When feeling overwhelmed by steep goals, ask for support to re-negotiate those goals.

- Keep expanding your resources by learning from important events in your life and from multiple people. Use your own or your peers’ experiences to learn what to do and what to avoid when facing dual-career challenges. Consult with the people you trust when you need help processing the lessons you have learned.

- Work on your time management by setting a daily schedule. Decide what is the most important task of the day and set aside the proper time for it first. Then, plan other activities around it, and do not forget to save time for recovery. Although the priority for that day might not be what you really want to do, put an earnest effort into it.

- Keep things in perspective and plan for the near- (days, weeks, months) and long-term (years) future, based on your past experiences and present situation. Planning should be flexible because life circumstances change, and plans must be adjusted.

- Watch your stress. Stress can be good if helps you grow. You should learn how to use good stress to your advantage, and how to recognize, avoid, and cope with unnecessary stress. Often, unnecessary stress comes from conflicting demands from authority figures. For example, a teacher might not be supportive of your athletic goals, or a coach might not see the value of academics. Do not keep such stress inside; communicate the situation to parents, counselors, or other people who support you.

- Stay positive! In the journey of life, there are no truly good or bad events, only opportunities for self-discovery and personal growth. Often, what looks like a loss might turn into a gain in the long run, but the opposite is also true. Therefore, learn from your past, live in the present, and plan for the future to be successful in your dual career and your life journey!

Glossary

Dual Career: ↑ Dual career is a combination of sport and studies (or work).

Resourcefulness: ↑ Resourcefulness is the degree and quality of resources the person has to reach the goal or meet the challenge in mind.

Resources: ↑ Resources are the person’s internal assets and relevant external factors facilitating goal achievement.

Dual-career Competencies: ↑ Dual-career competencies are experiences, knowledge, skills, and attitudes helping student-athletes to deal with dual career challenges. Such competencies create a good part of student-athletes’ resources.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

[1] ↑ Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R., and Tesch-Römer, C. 1993. The role of deliberate practice in acquisition of expert performance. Psychol. Rev. 100:363–406. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

[2] ↑ Knight, K. J., Harwood, C. G., and Sellars, P. A. 2018. Supporting adolescent athletes’ dual careers. The role of an athlete’s social support network. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 38:137–47. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.06.007

[3] ↑ Torregrosa, M., Ramis, Y., Pallarés, S., Azócar, F., and Selva, C. 2015. Olympic athletes back to retirement: a qualitative longitudinal study. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 21:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.03.003

[4] ↑ Stambulova, N., Engström, C., Franck, A., Linnér, L., and Lindahl, K. 2015. Searching for an optimal balance: dual career experiences of Swedish adolescent athletes. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 21:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.009

[5] ↑ De Brandt, K., Wylleman, P., Torregrossa, M., Lavallee, D., Schipper-van Veldhoven N., and Defruyt, S. 2018. Exploring the factor structure of the dual career competency questionnaire for athletes (DCCQ-A) in European pupil- and student population. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2018.1511619. [Epub ahead of print].