Abstract

You may have heard that humans spend about one third of their lives asleep. While sleep might seem like a passive activity, it is an active one that helps you focus and remember things in school, feel more emotionally balanced, and stay physically healthy. Experts recommend 8–10 h of sleep per night for teenagers and, at your age, that is hard to do. This article explains why sleep matters and how it impacts your physical and mental health. To help, we offer sleep tips like sticking to a sleep schedule and cutting down on screen time before bed. Prioritizing sleep will help you feel better, think sharper, and deal more effectively with social and emotional challenges.

Do You Get Enough Sleep?

How many hours of sleep do you get at night? Have you noticed that when you are not getting enough sleep, you might struggle to think as well or get more easily annoyed or sad? School schedules, extracurricular activities, and social activities all play a role in shaping how and when you sleep. Sleep is a passive or restful act, but it plays an active and important role: from helping you do well in school to making sure you feel good emotionally and physically [1]. The National Sleep Foundation recommends younger teens get more nighttime sleep than older teens and, by 18–25 years of age, teens should get the recommended amount for adults [2] (Table 1).

| 6- to 13-year-olds: 9–11 h |

| 14- to 17-year-olds: 8–10 h |

| 18- to 25-year-olds: 7–9 h |

- Table 1 - Recommended nighttime sleep by age.

Are you getting the recommended hours of sleep per night? Teenagers commonly experience poor sleep, including shorter periods of nighttime sleep, poor quality of sleep, and interruptions in sleep. In the rest of this article, we will explore why sleep is so important for you during this stage of life, how it affects your development, and what you can do to get better sleep.

What is Sleep?

First, what is sleep? When you sleep, your body goes through different sleep stages. There are two main types of sleep: non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep [1]. Throughout these two stages, sleep helps your brain store memories and learn how to identify, understand, and respond to emotions. Additionally, two main systems control your sleep. The circadian rhythm system, your body’s internal clock, that tells you when to be awake and when to sleep (also called your sleep-wake cycle), and it is influenced by cues like light and darkness. The sleep homeostasis system indicates your body’s need for sleep, like the way hunger indicates a need to eat. You have probably noticed that your hunger builds the longer you wait between meals, and it resets when you eat. Sleep homeostasis is similar—it builds the longer you stay awake and resets when you sleep. Circadian rhythms and sleep homeostasis work together to make sure you sleep and wake up at healthy times. They do not always work perfectly, especially during adolescence.

Some teenagers feel wide awake late at night, even if they must wake up early for school. This is because their sleep-wake cycles have shifted—their bodies want to go to sleep later and wake up later. This happens because melatonin, a hormone (chemical messenger) your body releases when it starts getting dark and that helps you feel sleepy, gets released much later in teens due to a change in circadian rhythms related to puberty [3]. This change, called a delayed sleep phase, is common among teenagers. Blue light from phones, tablets, and other screens can make things worse as blue light interferes with your body’s ability to make melatonin [4]. The more time spent looking at a screen before bed, the harder it might be to fall asleep. To make things worse, many teens experience “social jetlag” when their sleep and wake times differ between weeknights and weekends, because of social activities like hanging out with friends, using social media, or going to late-night events [3].

How Does Sleep Impact Development?

Sleep supports how well teenagers function in their daily lives, including the way their brains, emotions, and bodies works, which in turn affects how they think, feel, and act [5].

When you sleep, your brain organizes information from the day and gets ready for the next day, helping you remember things and learn new material better. Poor sleep negatively impacts your memory and decision making the next day. You might also feel sluggish, have difficulty paying attention, or make more mistakes because your brain did not renew itself during sleep. Poor sleep can make it harder to focus, solve problems, and do well in school and while driving [6].

Sleep also impacts your mental health, meaning how you feel emotionally. Poor sleep can increase the intensity, or how strongly you feel stressed, anxious, or depressed; whereas getting enough sleep can reduce the intensity of these symptoms. When you are tired, you may find it harder to cope with your feelings and you may feel more irritable, frustrated, or overwhelmed than usual. Sleep helps your brain cope with emotions. When you are rested, you may react less strongly in triggering situations. For example, you may be more likely to slow down and take deep breaths than snap at someone. You may even feel less frustrated.

Sleep also impacts your physical health. Teenagers who have poor sleep are at higher risk of obesity because sleep affects the body processes that help control hunger and appetite [7]. Teens with poor sleep tend to have poor eating habits, like eating more unhealthy food. Also, your body repairs itself while sleeping, so without enough sleep, your immune system weakens, making it harder to fight off sickness [8]. On the flip side, getting enough sleep will help you stay physically and mentally healthier, so that you can perform at your best every day.

What If I Am Not Quite a Teenager?

Even if you are not a teenager yet, a lot of this is similar for you! You have a sleep-wake cycle too, and blue light can also confuse your body into thinking it is still day and not time to start getting ready for bed. You may have already noticed how poor sleep has impacted your mental and physical health, like your emotions, eating habits, and daytime functioning. Learning about the importance of sleep before you become a teenager will help you get ready to sleep well when you are one!

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep hygiene consists of habits that can help improve your sleep. Here are some sleep hygiene tips that can help you catch more “zzz”s (summarized in Figure 1) [4]:

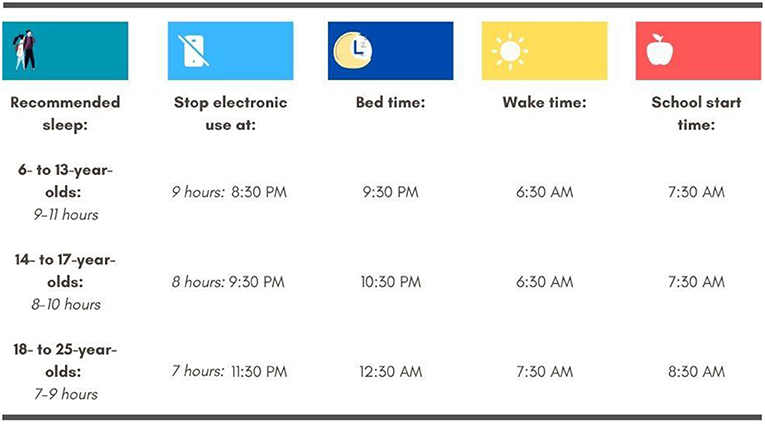

• Stick to a schedule: try to go to bed and wake up at the same time every day, even on weekends, according to the guidelines in Figure 2. This will help set your body’s clock, so you feel tired enough to sleep at night and awake and alert during the day.

• Limit screen time before bed: avoid using your phone, tablet, or computer at least an hour before bed. The blue light from these screens interferes with your body’s ability to make melatonin and makes it harder to sleep. The stimulation caused by using electronic devices can also make it hard to sleep. The mind and body need time to wind down, become sleepy, and learn that it is time to go to bed.

• Create a sleep-friendly environment: make your bedroom as comfortable as possible to help your body feel sleepy and not distracted. Keep it cool, quiet, and dark. Use earplugs or a white noise machine to reduce noise, and consider blackout curtains to reduce light.

• Avoid caffeine in the afternoon and evening: caffeine can make it harder to fall asleep or can increase the possibility of interrupted sleep because it prevents the body from feeling the need to sleep. So, skip that soda, matcha, or coffee in the later part of the day.

• Take short “cat” naps: if you are really tired during the day because you did not sleep well at night, take a quick 15–30-min nap as early in the day as possible. Late or long naps can make it harder to fall asleep at night, but an early, short nap can refresh you without affecting your sleep schedule. If it is too late to take a short nap, try doing a restful activity like stretching.

- Figure 1 - Sleep hygiene.

- Sleep hygiene involves habits that can help improve your sleep. Here are some simple tips you can follow to ensure that you get your recommended number of hours per night.

- Figure 2 - Guided schedule.

- This is an example schedule for getting enough sleep at night. The examples are provided per age range, but the school start times might be different for you. You can start by picking the time you need to wake up for school, then count back the hours of sleep you need to find your bedtime. Make sure to turn off all screens about one hour before bedtime, to help you start feeling sleepy.

In summary, sleep is really important for people of all ages, and especially for teenagers. While it might be hard to get enough sleep with all the things going on in your life, making sleep a priority will help you feel and perform better in the long run. Follow the sleep hygiene tips above to start improving your sleep habits, and you will soon notice the difference in how you feel and function every day.

Glossary

Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM): ↑ The quiet or restful phase of sleep when a person’s brain activity, breathing, and heart rate slow down, body temperature drops, muscles relax, and eye movements stop.

Rapid Eye Movement (REM): ↑ Stage of sleep with rapid eye movements and heightened brain activity, typically associated with dreaming and creating memories. Occurs roughly 90 min after falling asleep and repeats throughout the night.

Circadian Rhythm: ↑ The body’s internal clock that tells you when to sleep and wake up.

Sleep Homeostasis: ↑ The process that balances sleep and wake time. Your body’s need for sleep increases the longer you are awake and returns to normal once you sleep.

Melatonin: ↑ A hormone (chemical messenger) that helps you feel sleepy.

Delayed Sleep Phase: ↑ When the body’s internal clock is shifted later than the normal day-night cycle, causing someone to fall asleep and wake up much later.

Obesity: ↑ When someone’s body has more fat than what is considered healthy for their age, height, and body type.

Immune System: ↑ The body’s personal defense team made up of cells, tissues, and organs that work together to protect the body from harmful germs like bacteria.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

[1] ↑ Tarokh, L., Saletin, J. M., and Carskadon, M. A. 2016. Sleep in adolescence: physiology, cognition and mental health. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 70:182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.008

[2] ↑ Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., Alessi, C., Bruni, O., et al. 2015. National sleep foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 1:40–3. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010

[3] ↑ Crowley, S. J., Wolfson, A. R., Tarokh, L., and Carskadon, M. A. 2018. An update on adolescent sleep: new evidence informing the perfect storm model. J. Adolesc. 67:55–5. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.06.001

[4] ↑ Lebourgeois, M. K., Hale, L., Chang, A. M., Akacem, L. D., Montgomery-Downs, H. E., Buxton, O. M., et al. 2017. Digital media and sleep in childhood and adolescence. Pediatrics 140:S92–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1758J

[5] ↑ Galván, A. 2020. The need for sleep in the adolescent brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2019.11.002

[6] ↑ Martiniuk, A. L. C., Senserrick, T., Lo, S., Williamson, A., Du, W., Grunstein, R. R., et al. 2013. Sleep-deprived young drivers and the risk for crash the drive prospective cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 167:647–55. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1429

[7] ↑ Okoli, A., Hanlon, E. C., and Brady, M. J. 2021. The relationship between sleep, obesity, and metabolic health in adolescents: a review. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 17, 15–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coemr.2020.10.007

[8] ↑ Orzech, K. M., Acebo, C., Seifer, R., Barker, D., Carskadon, M. A., Bradley, E. P., et al. 2014. Sleep patterns are associated with common illness in adolescents. J. Sleep Res. 23:133–42. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12096