Abstract

When someone you care about dies, your body goes through a process called grief. Grief is one of the feelings people experience after losing someone they care about. When you are around someone you care about, your body releases a special chemical signal called oxytocin. Scientists are still learning about what happens to oxytocin when a loved one dies. When you grieve someone, you may cry or be angry, but the brain—your body’s control system—experiences grief as well. In this article, I will tell you about the parts of the brain that are affected by grief, and how they change as people cope and grow (Teachers and parents: This article discusses death).

What is Grief?

Most of us have lots of people in our lives whom we love: our parents, grandparents, siblings, and other relatives. Even our teachers, coaches, friends, and pets can be special to us. Unfortunately, sometimes the people or pets we love die. Death is a part of life, but scientists are still not sure what happens to us after we die. When someone dies, their body stops working—they no longer breathe, walk around, eat, or feel, and they cannot come back to life. People can die from many causes. Perhaps they have been living a long time, and their bodies have worn down, or maybe they are very sick. Sometimes, people die suddenly because of accidents or causes no one understands.

Regardless of when or how it happens, when someone you love dies it is very hard. You will feel a lot of big feelings. You may cry, feel angry, or feel confused. All of these feelings are okay and normal. Losing someone you care about really hurts. You may notice that the feelings you experience after someone you love dies are different from other times you have felt angry, sad, or confused. These are not the same feelings as when you lose a sports game, drop an ice cream cone, or do not understand a math problem at school. The feelings people feel after losing someone they care about are part of a response called grief.

Oxytocin: The Special Signal

When you grieve for someone, it means that you really care about that person. The brain, which controls what people do and how they think, releases a special chemical signal called oxytocin that helps you remember people who are extra special. Oxytocin is released when you see, spend time with, or even hug the special people in your life, and it begins to be produced when you are just a baby! Right after you were born, both your brain and your mother’s brain released oxytocin to remind you both how special you would be to each other and that you were safe together [1]. Oxytocin reminds you that the special people in your life care for you, and that you care for them (Figure 1). Even as you grow up, your brain will continue to release oxytocin when you get a hug from your mom or dad.

- Figure 1 - Hugging people you care for causes your brain to release oxytocin, which makes you feel safe and good (Figure created using ChatGPT).

Grief Inside the Brain

Scientists are still learning about the way a person’s oxytocin production changes when someone they care for dies. However, they have learned that the brain definitely feels the effects of the loss of a loved one, which may explain some of the feelings people experience when they are grieving. The brain is a very complex organ that controls almost everything the body does (remember to say “Thank you, brain!”). The brain has many parts, each with a different job. To explain the way grieving affects the brain, imagine the brain as a house, and each of the different parts as a separate room (Figure 2).

- Figure 2 - Your brain has different parts, or “rooms”, that perform different functions.

- The reward room helps you notice good things. The habit room helps you learn routines, like brushing your teeth! The emotions room allows you to recognize different feelings. The memory room stores experiences for you to look back on. The pain center helps you notice when something is hurting (Brain and roof images from Canva).

In the brain’s “reward room”, you might find lots of toys, games, and comfy chairs. The brain’s reward room is the spot where you feel rewarded, so you might find some oxytocin there. The reward room is also involved with bonding with others, so you might find pictures of your friends and family hanging on the walls. When you are proud of yourself or eat a yummy chocolate bar, there is lots of activity in the reward room. There may be activity in the reward room when you are grieving, too [2]. This is not because you are feeling rewarded, but because you are missing and thinking about the special person who has died [2].

Grief also affects the brain’s “pain center” [2]. The pain center is full of switches and levers that signal when you have hurt yourself, and it has shelves full of past pains. When you fall and scrape your knee or get called a mean name, you feel hurt, and these hurt feelings come from the pain center. When you grieve for a special person, you may feel hurt because you miss them, and these hurt feelings also come from the pain center [2].

When you are grieving, it is natural to experience big emotions such as fear, sadness, and anger. These feelings come from your brain’s “emotions room”. This is a small but important room where you keep strong feelings and emotional memories on the shelves. When you are grieving, the emotions room is on high alert, because losing someone is an intense experience that requires the emotions room to use intense emotions to help you feel your grief [3].

The brain’s “habit room” is also an important part of why you feel grief. The habit room may look like an office where homework is done. Normally, it is very clean and organized. The habit room is responsible for your habits—things you expect to happen each day, as well as things you have learned to be true. For example, you may expect school to start at 8:00 a.m., or expect to see your dog when you get off the bus. When someone you care about dies, your life is disrupted, and your habit room becomes messy [4]. Things you expect to happen, like seeing your special person, do not happen anymore. This can make you, and your brain, very confused.

One reason your habit room is such a mess is because there is a wall between your habit room and your memory room. The memory room houses all your memories, so you might remember learning that someone has died. You might remember going to a funeral or memorial service. However, because of the wall between your memory room and your habit room, the habit room does not know that someone has died and will be a mess until new habits form without your special person [4] (Figure 3).

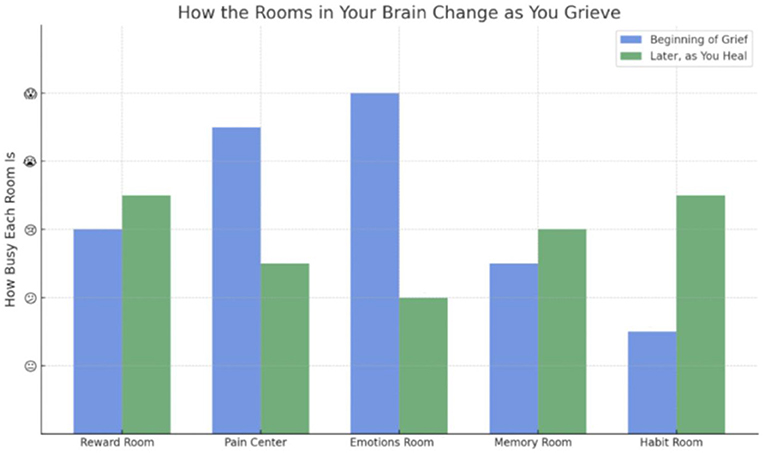

- Figure 3 - At the beginning of grief, the emotions room and pain center are very active (blue bars).

- Over time, as you heal, the memory, reward, and habit rooms become more active (green bars). Your brain is always working to help you through your grief (Created using ChatGPT).

How Does the Brain Change After Grief?

Learning new habits and living your life without your special person can be really difficult and each day can be different. Some days you might feel good—you might learn new things in school, play games with friends, or read a good book. Other days, you might feel more grief—you might cry or feel angry at others or have a hard time focusing on other things [5]. This is okay. When you grieve, your brain is learning what life is like without your special person, and that takes time.

It might be sad or scary to think about your brain changing after losing someone you care about. However, one thing that is special about human brains is their ability to care about others. Ultimately, when you are feeling grief, it is because you cared about that person. Your brain’s different parts, such as the reward room, pain center, and emotions room, allow you to feel the feelings that you experience, such as excitement, love, fear, and even grief. Without these big feelings, life would be pretty boring.

Even though the habit room will undergo some changes to make up for your missing person, you will have your memory and reward rooms to thank for keeping your loved one in your mind even after they have died. The memories you have of your special person and the pictures in the reward room will stay on the “walls” of your brain, long after your special person is gone.

Even though grief is difficult for everyone, the brain and its “rooms” allow you to continue to live your life, grieving as you need to grieve, and remembering the people you loved along the way.

Glossary

Grief: ↑ The human response to losing someone you care for. Grief can be an emotional and/or physical response that may cause you to feel a wide range of emotions, such as sadness or anger.

Oxytocin: ↑ A chemical signal in the body that is released when you are with someone that is special to you, like your family members. Oxytocin helps you know you are safe.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

All figures were produced by PCM, 2024.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author(s) declare that generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT) was used to assist in the creation of Figures 1 and 3 of this manuscript. Generative AI was not used to generate or analyze data, interpret results, or write the manuscript text. All AI-assisted content was reviewed and verified by the authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

[1] ↑ Pohl, T. T., Young, L. J., and Bosch, O. J. 2019. Lost connections: oxytocin and the neural, physiological, and behavioral consequences of disrupted relationships. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 136:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2017.12.011

[2] ↑ O'Connor, M. F., Wellisch, D. K., Stanton, A. L., Eisenberger, N. I., Irwin, M. R., and Lieberman, M. D. 2008. Craving love? Enduring grief activates brain’s reward center. NeuroImage 42:969. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.256

[3] ↑ Chen, G., Ward, B. D., Claesges, S. A., Li, S. J., and Goveas, J. S. 2020. Amygdala functional connectivity features in grief: a pilot longitudinal study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28:1089. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.02.014

[4] ↑ Kakarala, S. E., Roberts, K. E., Rogers, M., Coats, T., Falzarano, F., Gang, J., et al. 2020. The neurobiological reward system in Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD): a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 303:111135. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2020.111135

[5] ↑ Stroebe, M., Schut, H., and Boerner, K. 2010. Continuing bonds in adaptation to bereavement: Toward theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30:259–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.007