Abstract

Galleria mellonella, known by most people as the greater wax moth, is an invertebrate animal (one without a backbone). Its life cycle consists of four stages: egg, larva, pre-pupa/pupa and adult moth. In nature, these larvae inhabit bee hives, so they are commonly considered a pest of honeybee colonies. Despite that, they have been attracting increasing interest among scientists. The larval stage has been used to study treatments for several diseases caused by microbes, and they can also be used as an alternative test model in research—helping to reduce the number of vertebrate animals, like rats and rabbits, used in scientific studies. Galleria mellonella has another superpower: it can help break down plastics. Are you wondering what else this tiny friend of science is capable of? Keep reading our article to find out even more about Galleria mellonella!

What is Galleria mellonella?

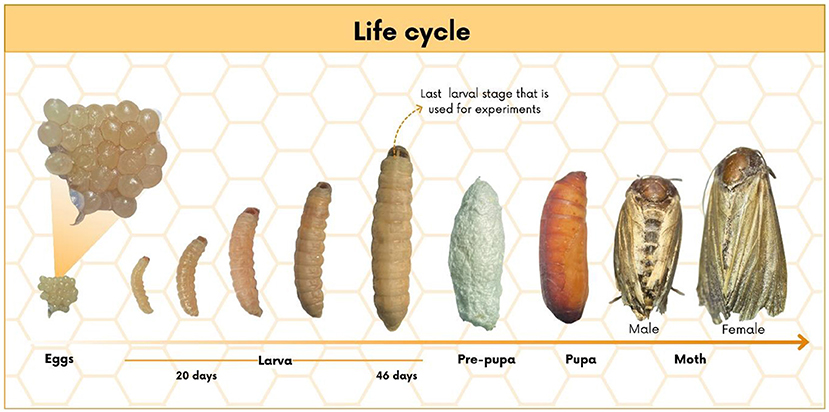

Galleria mellonella, commonly known as the greater wax moth, is an invertebrate animal (meaning it has no backbone). Its life cycle happens in four stages: egg, larva, pre-pupa/pupa and adult moth. The complete life cycle of Galleria mellonella, from egg to adult moth, takes about 15 weeks [1]. At temperatures between 25 and 30°C, the eggs usually hatch in about 10 days. Once the eggs hatch, the larvae grow and go through several stages, reaching up to 3 cm in size. The larval stage can last up to 7 weeks. During this stage, they produce protective silk threads. When they reach the pre-pupa stage they stop feeding and, over time, reduce their movements until they become pupa (pupa stage) [2].

The transition from pupa to moth can take up to 8 weeks. During this period, the insect does not eat because its mouth parts shrink and stop working. Male and female adult moths may look similar, but males are smaller and pale, while females are larger, with a dark red-brown hue (Figure 1) [2]. Female moths can lay 50–150 eggs. Once the female lays her eggs, her job is done and she dies.

- Figure 1 - Stages of Galleria mellonella life cycle: egg, larva, pre-pupa, pupa, and moth.

In nature, these larvae live in beehives, where they eat honey, wax, and pollen. For this reason, they are known as pests in honeybee colonies, and they are often a real nightmare for beekeepers. Despite that, they have been attracting increasing interest among scientists because the larvae offer unique advantages [3]. Larvae are easy to grow and maintain in the lab, without the need for complex or expensive setups. They can be kept at 37 °C, which is the ideal temperature for studying infections caused by various microbes. In addition, their immune system is similar to that of vertebrates (like us), which allows the larvae to be used as a screening model before moving on to tests in vertebrate animals [1].

What do the Larvae Look Like, and How do They Fight Off Microbes?

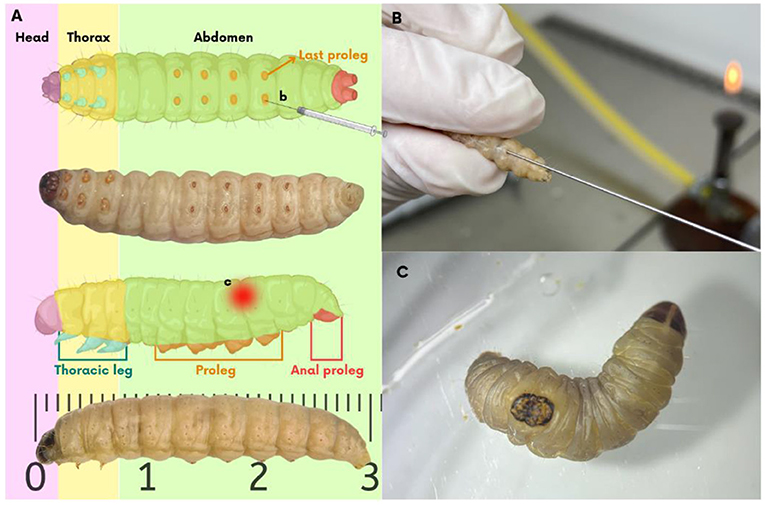

In most cases, Galleria mellonella larvae are light-colored and can become dark red-brown as they approach the pre-pupa stage. Their bodies have three regions: head, thorax, and abdomen. The head has a pair of false eyes, a pair of true eyes, special mouthparts called the maxillae and mandible, and antennae. The thorax bears six legs, and the abdominal region has 8 false legs called prolegs. The last abdominal segment has a pair of anal prolegs. Internally, larvae have a digestive tract, a primitive nervous system, and silk-production glands used for cocoon formation and protection. The larvae have hemolymph, a blood-like body fluid that acts as a line of defense. On the outside, the larvae have a cuticle—a special kind of skin that protects the body (Figure 2) [3].

- Figure 2 - For experiments, we used larvae in their final stage, weighing between 200 and 250 mg, with light-colored cuticle and free of spots.

- (A) The head is highlighted in purple. Yellow indicates the thorax region, with six legs in blue. Green shows the abdominal region, with eight prolegs in orange and the anal prolegs in red. (B) To infect Galleria mellonella with microorganisms, the microorganisms are injected through a tiny syringe inserted into their last proleg. (C) To simulate a skin infection, a heated steel instrument is applied to the back of the larva, and the burn wound is infected.

In humans and other mammals, invasion of microbes activates the immune system—the defense mechanisms found in the blood of mammals. Similarly, Galleria mellonella also have defense mechanisms. The cells in the hemolymph responsible for activating their defense mechanisms are called hemocytes. Hemocytes can recognize microbes invaders and capture and destroy them with the help of special antimicrobial proteins—helping the larvae to fight back [1].

The use of Galleria mellonella larvae to study the immune response can be compared to one of the most famous stories in the world—Alice in Wonderland. In the book, Alice meets the Red Queen. They both run very fast, however, when exhausted, Alice stops and realizes that they are still in the same place. Then, the Red Queen explains to Alice: “Here, as you see, you have to run as fast as you can to continue in the same place....”. This phrase was used by scientists to explain that all organisms need to adapt over time, to change in order to survive. In immunology, this concept suggests that both microbes, like bacteria and fungi, and their hosts, like humans, need to keep evolving, to survive and avoid extinction. This theory is called the Red Queen Hypothesis.

Because both the Galleria mellonella and mammalian immune systems can recognize and combat various microbes, many studies have used Galleria mellonella to answer questions like: “How does the immune system react and how microbes, like bacteria and fungi, cause diseases?” or “What are their mechanisms?” or “What helps these microbes survive and spread?”. Research on Galleria mellonella can also help scientists test whether new drugs work or whether they are toxic. The results obtained using larvae can help scientists decide whether further tests are needed on vertebrates, like mice or rabbits.

How Else Can Galleria mellonella Help Scientists?

Every year, hundreds of millions of tons of plastic are thrown away. Less than 10% of this material is recycled, which is worrying because it takes some plastics more than 450 years to break down. This makes it very important to find ways to address this environmental problem [4].

Galleria mellonella could be a valuable option, since it can consume several types of plastic quickly and efficiently, such as polyethylene (LDPE), found in plastic bags and water bottles; biaxially oriented polypropylene (BOPP), used in packaging and stickers; and expanded polystyrene (EPS), the foam commonly used in buildings [4]. Although it is not yet fully understood how the larvae break down plastics, evidence suggests that enzymes present in their saliva, along with the natural bacteria in their intestines, play an active role, contributing to plastic degradation [4].

Is It Fair to Use Animals in Science?

For any kind of animal, it is impossible to talk about animal testing without dealing with ethical concerns. For over 60 years, global rules for the use of vertebrate animals have been based on the “3 Rs principle” (replace, reduce, and refine). In other words, when planning a research project, it is our duty to try to find alternatives to the use of animals whenever possible. If animal use has major benefits, then the researcher must minimize the number of animals needed. And, as a final point, refine the methods, seeking to reduce animal suffering as much as possible.

However, these guidelines do not extend to invertebrates, which allows their large-scale use as an alternative and reduces reliance on vertebrates. Invertebrate alternatives have gained popular support. Nevertheless, some researchers are pushing for ethical responsibility in the use of invertebrates in research, arguing that, like vertebrates, they are also living beings capable of experiencing discomfort, pain, and suffering during experiments.

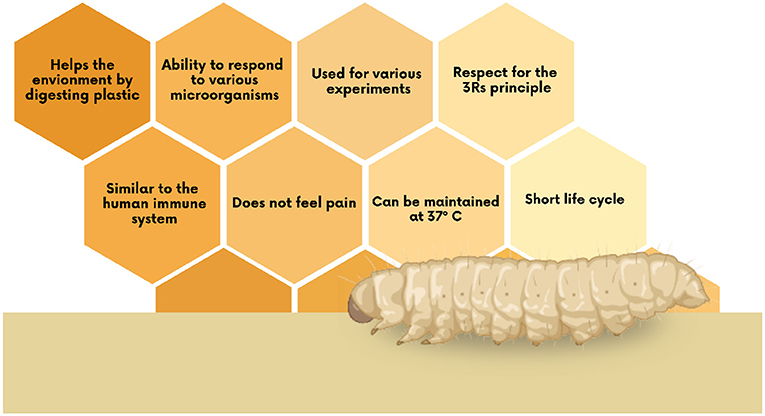

Figure 3 summarizes the advantages of using Galleria mellonella in experiments.

- Figure 3 - Advantages of using Galleria mellonella for studies in the health field and beyond.

Mission Accomplished: Galleria mellonella, the Tiny Heroine of Science

Galleria mellonella larvae used to be fish bait—but now they are helping scientists in various ways, and have made important contributions to scientific research in recent years. By breaking down plastics, these larvae may be able to help societies deal with the increasing amounts of plastic pollution. However, we need more studies to understand how the larvae actually do this. Future research could help reduce the environmental impact of the trillions of plastic products produced every year. Additionally, Galleria mellonella’s similarity to the mammalian immune system makes it an ideal test model that supports the 3 Rs principle regarding use of vertebrate animals in research. As a result, Galleria mellonella continues to gain recognition in the scientific community. Did you imagine that a simple insect could contribute so much to the advancement of science and the environment?

Glossary

Larva: ↑ Is the young stage of some insects. During this stage, they grow, feed, and prepare for metamorphosis.

Pupa: ↑ Is the transformation stage between the larva and the adult. In this stage, the insect’s body changes completely during metamorphosis.

Immune System: ↑ A set of cells, tissues, and organs responsible for defense against invading microorganisms.

Hemolymph: ↑ Liquid that circulates in the body of invertebrate animals, similar to blood. It transports nutrients and defends the body against diseases.

Hemocytes: ↑ Are the defense cells found in the hemolymph of insects. They help defend against microorganisms and heal wounds.

Enzymes: ↑ Proteins that function as “machines” that speed up chemical reactions in the body.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Auxilio FAPESP 2024/04696-4.

AI Tool Statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

References

[1] ↑ Tsai, C. J., Loh, J. M., and Proft, T. 2016. Galleria mellonella infection models for the study of bacterial diseases and for antimicrobial drug testing. Virulence 7, 214–29. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2015.1135289

[2] ↑ Jorjão, A. L., Oliveira, L. D., Scorzoni, L., Figueiredo-Godoi, L. M. A., Prata, M. C. A., Jorge, A. O. C., et al. 2018. From moths to caterpillars: ideal conditions for Galleria mellonella rearing for in vivo microbiological studies. Virulence 9, 383–9. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2017.1397871

[3] ↑ Durieux, M. F., Melloul, É., Jemel, S., Roisin, L., Dardé, M.-L., Guillot, J., et al. 2021. Galleria mellonella as a screening tool to study virulence factors of Aspergillus fumigatus. Virulence 12, 818–34. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1893945

[4] ↑ Burd, B. S., Mussagy, C. U., de Lacorte Singulani, J., and Tanaka, J. S. 2023. Galleria Mellonella larvae as an alternative to low-density polyethylene and polystyrene biodegradation. J. Polym. Environ. 31, 1232–41. doi: 10.1007/S10924-022-02696-8/FIGURES/7